Estimating the effects of a major reform in additional child benefits granted to German low-income households

Abstract

This research note provides a short overview of the difficulties associated with the estimation of the short-term fiscal effects of a major reform in additional child benefits granted to German low-income households. We briefly discuss the methodology used to construct both an appropriate database and to operationalise the microsimulation model. Of particular note are the imputation of heating costs and the conversion of that part of household incomes used to determine past entitlement to additional welfare benefits (accountable income) into gross household incomes. Finally, the role of the model within the legislative process is roughly outlined.

1. Introduction

In late 2008, the German Government implemented a major policy reform aimed at increasing the number of children entitled to a specific additional child benefit (Kinderzuschlag, abbreviated: KiZ) from approximately 1,00,000 to 2,50,000. On behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (BMFSFJ), the Fraunhofer Institute for Applied Information Technology provided cost estimates on the basis of the microsimulation model MikMod-KiZ. This research note provides a short overview of the difficulties associated with the estimation of the short-term fiscal effects of this reform and the methodology used to construct both an appropriate database and to operationalise the microsimulation model. In fact, MikMod-KiZ consists of three independent static microsimulation models targeted at different groups of potential recipients, all using different data sources. One model is used to calculate the effects of policy changes on current recipients. A second model aims at low-income households with incomes above the level that qualifies for social welfare payments. The third focuses on those currently receiving social welfare benefits. Since the major objective of the reform was to entitle additional social welfare recipients to the KiZ, in the following we will describe the data and model used to estimate the reform effects on this specific group only.

2. Database construction

The German additional child benefit (KiZ) was introduced in 2005 in order to support families to overcome need in cases where this is only the case due to the existence of children. Because of the complex interactions with means tested social welfare benefits and housing allowances granted to non-needy low-income families, this leads to a situation where benefits are only granted to families within a very small income bracket. (For a more detailed description of the KiZ, see Knabe, 2005.) As a consequence, the KiZ is granted to far less than 1 percent of German children.

Evidently, any estimate of the reform effects thus requires a database that covers this specific income bracket with an appropriate number of observations. The major problem is that, since the major social welfare reform in 2005, there exists no accessible microdatabase with a focus on social welfare recipients. A representative large-scale sample that covers one fourth of all social welfare recipients is available only for the years before 2005. Despite the fact that it is already dated and therefore does not include information about a sizeable number of households which have become entitled to welfare benefits since the 2005 reform act, the major drawback of this database is that some of the data essential to calculate claims under current law is either missing or must be derived from partly incomplete data. However, due to the absence of alternative data sources, this sample forms the basis of our microsimulation model.

For our simulation model, we are basically interested in household income and in household need. As heating costs are a fundamental determinant of household need, in a first step, data on household’s heating costs have to be imputed. Within our ad-hoc imputation procedure it is assumed that heating costs can be expressed as a fraction of total rent, and that this fraction is uniformly distributed between 0 and 0.15. Such a uniform distribution is broadly consistent with results taken from the latest German Income and Expenditure Survey. However, even if this imputation procedure may not capture all heating costs correctly, later data adjustments (described below in Section 3) minimize these possible errors.

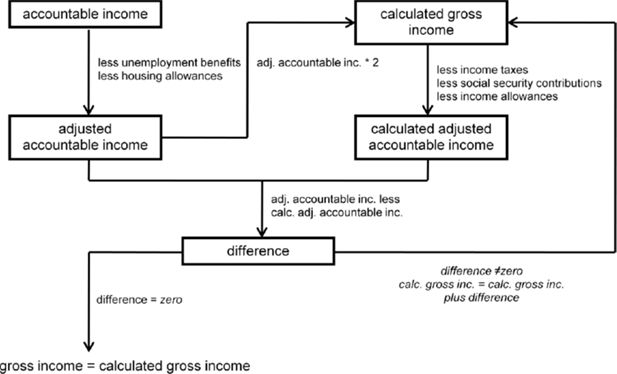

In a second step, we use the information on ‘accountable’ household income included in our database to derive gross household income. Accountable income is that part of household income used to determine household entitlement to welfare benefits. The conversion to gross income is required for means-testing of household welfare entitlements under "current law" and various “reform” scenarios. In order to convert accountable to gross income, income taxes, income allowances and social security contributions have to be calculated. Since these (non-linearly) depend on gross income, we use the iterative imputation process depicted in Figure 1.

Initially, accountable income is adjusted for all cases in which social welfare benefits topped up unemployment benefits or where a housing allowance was granted under the previous law. Multiplying this “adjusted accountable income” with a factor of two gives a first “calculated gross income” from which income taxes, social security contributions and income allowances are computed and deducted. The resulting “calculated adjusted accountable income” is then compared with actual “adjusted accountable income”. If both are equal, “calculated gross income” is taken for subsequent calculations under the current law. If they differ, the difference is calculated, added to “calculated gross income”, and the cycle of calculations is repeated.

3. Microsimulation

Using information included in the edited database, our microsimulation model computes potential claims for the KiZ and tests whether the conditions for entitlement are fulfilled. These tests involve the calculation of social welfare benefits, hypothetical benefits if the family has had no children and the calculation of housing allowances. The calculation of housing allowances is necessary since KiZ is only granted to needy families if this helps to overcome need. KiZ payments alone exceed social welfare payments only in a small number of cases. In most cases, KiZ payments and housing allowance – which, since 2005, are only granted to households that do not receive welfare benefits – together exceed social welfare payments.

Clearly, even with the adjustments described above, our database of social welfare recipients is not able to replicate the status quo, especially since it covers only a fraction of today’s recipients. However, the model design accounts for this fact. In a first step, the model calculates results for the given law. These results are stored in a special output-vector. In a second step, the policy reform is simulated but results are stored in a different output-vector. We then use a static aging approach (see e.g. Merz, 1986) to adjust the results of the first simulation to available consolidated statistics on social welfare recipients. These statistics, covering the year 2007, come from the German Federal Employment Agency (BA) and provide information about the number and type (married or unmarried, number of children) of households within a certain income bracket as well as their social welfare benefits and housing costs. Case specific weighting factors in the microdatabase are then adjusted such that aggregated results stored in the first simulation round resemble the official numbers provided by the BA as good as possible. The algorithm used for this adjustment is programmed by Hermann Quinke. Based on the Minimum Information Loss Principle and employing the standard Newton-Raphson solution it is more or less identical to Merz’s ‘Adjust’ reweighting algorithm (Merz, 1994). The total number of restrictions put on the dataset within this adjustment process is 540.1 A comparison between the adjusted microdata and the corresponding official statistics shows no statistically significant difference with respect to central tendencies as far as they are inferable from the aggregated official statistics. Using the adjusted weighting factors, the effects of the policy reform can then be immediately derived by aggregation of weighted differences in the two output-vectors.

4. Impact on policy-making

Results of the microsimulation model directly entered the bill of the late 2008 reform act. As estimated reform costs as well as their distribution on different layers of government were subject to fiscal constraints, the model was extensively used beforehand to evaluate possible reforms that bail out predefined fiscal effects. Therefore, our results had a large impact on the extent of the final reform. Subsequently, the model has been used to evaluate the impact of policy changes in different areas of the social security system that interact with the KiZ. Examples include changes in child allowances, housing allowances or (annual) increases in social welfare benefits. All this research is conducted on behalf of the BMFSFJ.

Footnotes

1.

The number of social welfare recipients differentiated by gross wage income (20 income brackets) and family type (9), the number of social welfare recipients differentiated by social welfare benefits (20 brackets) and family type (9), and the number of social welfare recipients differentiated by housing costs (20 brackets) and family type (9). This gives 3*20*9 = 540 independent restrictions.

References

-

1

Erwerbstätigenfreibetrag und Kinderzuschlag: Adverse Arbeitsanreize bei Hartz IVSozialer Fortschritt 54:220–226.

-

2

Structural Adjustment in Static and Dynamic Microsimulation ModelsIn: G Orcutt, J Merz, H Quinke, editors. Microanalytic simulation models to support social and financial policy. Amsterdam: North-Holland, Elsevier. pp. 423–446.

-

3

The Adjustment of Microdata Using the Minimum Information Loss Principle. Discussion paper 8Department of Economics and Social Sciences, University of Luneburg.

Article and author information

Author details

Acknowledgements

This research note is based on work jointly carried out with Hermann Quinke. I want to thank him as well as Paul Williamson for constructive comments and suggestions that certainly helped to improve the quality of the paper. The usual disclaimer applies.

Publication history

- Version of Record published: December 31, 2009 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2009, Stöwhase

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.