Towards a European union child basic income?: Within and between country effects

Abstract

This paper explores the within and between country distributional implications of an illustrative Child Basic Income (CBI) operated at EU level. Using EUROMOD, we establish that a universal payment of €50 per month per child aged under 6 could take 800,000 children in this age group out of poverty. It could be financed by an EU flat tax of 0.2% on all household income, assuming that it would also be taxed nationally as income. Most member states and virtually all families with children aged under 6 would be net gainers. We simulate two versions of EU CBI, with the benefit rate of €50 per month adjusted or not for differences in purchasing power between member states. In general, fiscal flows between member states, and also poverty reduction, would be smaller under the adjusted version. The political feasibility of such a scheme might be questioned, especially within the net contributor countries. Nevertheless, for those seeking ways to strengthen solidarity across national boundaries, a scheme supporting the incomes of families with young children, wherever in the EU they might reside “could be a demonstration of the EU’s commitment to children, to the future” (EC 2012a: 62).

1. Introduction

The idea of an EU-wide child basic income scheme, the subject of this paper, has a long pedigree and some recent relevance. In response to the charge that a basic income scheme would be unworkable and/or infeasible, its advocates have often pointed out that something resembling a basic income does already exist in several countries, in Europe and beyond, albeit only available to persons of non-working age: the elderly (in the form of a universal basic pension), and children (in the form of a universal child benefit).

In fact, as the latest version of MISSOC (2012) informs us, universal child benefits seem to be the rule in Europe. In mid-2012, family allowances did not vary with income in 18 out of 27 EU countries (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Sweden, The Netherlands, United Kingdom), and in 3 out of 4 EFTA member states (Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland). Child benefits were income tested only in Southern Europe (Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, Spain), in 3 Eastern European countries (Czech Republic, Lithuania, Slovenia), and in Iceland (an EFTA member state).

Of course, as the case of the UK indicates, where from 2013 about 1.2 million out of 7.9 million families with children had their entitlement reduced or terminated, universal child benefits are not always popular with governments. But elsewhere in Europe, the direction of policy change was the opposite (Bradshaw & Finch 2002). In Germany, for instance, not only were child benefits not made subject to a means test, but their value was significantly increased in the mid-1990s (Tamm 2010), while current policy debates are about whether they should considerably increase again.

The reason universal child benefits have on the whole been resistant to policy change is that the standard arguments in their favour remain strong. In terms of horizontal equity, if one accepts that children can to some extent be viewed as a public good, then shifting some of the costs involved from families with children to society at large must enhance social welfare. In terms of vertical equity, where existing policies leave coverage gaps, universal child benefits will also improve the position of families at the bottom of the income scale (often failing to take up or ineligible for assistance under current policies).

In view of the above, extending universal child benefits to the entire EU can be seen as a rather modest proposal. But what is the case for a child basic income at EU level, funded (at least partly) out of the EU budget? Can such an idea be taken seriously as a reasonable candidate for an ambitious EU policy initiative in an area traditionally ruled by the principle of subsidiarity (dictating that the EU should not undertake action unless that action is more effective than that taken at national, regional or local level)?

The question is obviously legitimate, but the best answer to it comes in a recent European Commission publication cautiously floating the idea. A child basic income scheme “could be a demonstration of the EU’s commitment to children, to the future, and could contribute to the reduction of child poverty. It would also document the solidarity existing between people without and with children.” Furthermore, it might be useful in the current economic crisis: “While not as effective a stabilizer as unemployment insurance per se (because of little cyclical increase on the expenditure side), an EMU-wide child basic income scheme, if jointly financed, would ease the situation of countries that face massive shocks.” (European Commission 2012a: 62).

As the report went on to note, “such schemes have been advocated by prominent academics including Atkinson and Marlier (2010).” In fact, the latter have come out strongly in favour of a “concrete proposal” that “the EU introduce a Basic Income for Children”. In their version of such as scheme, “each Member State would be required to guarantee unconditionally to every child a basic income, defined as a percentage of the Member State median equivalised income (and possibly age-related). Implementation would be left to Member States, who could employ different instruments. The minimum could be provided via child benefit, via tax allowances, via tax credits, via benefits in kind, or via employer-mandated benefits. The only restriction is that the set of instruments selected must be capable of reaching the entire population.” (Atkinson & Marlier 2010: 34).

As Atkinson and Marlier argued (2010: 34), “the paramount reason for proposing an EU basic income for children is concern about child poverty. But a second reason for proposing an EU basic income for children is that it would contribute positively to other EU headline objectives. The risks of poverty and social exclusion among children are important in their own right, but they also have implications for the future.”

With respect to the latter point, the accumulated evidence on the lifetime costs of child poverty and the benefits of early intervention is more than sufficient; for a review see Esping-Andersen (2002) and Kamerman et al. (2003). On the other hand, the economic crisis has made the former point even more pressing. As a recent report explains (European Commission 2012: 41), “child poverty has risen in 18 Member States since 2008, sometimes in a significant manner”, chiefly as a result of the adverse effects of the recession on the working age population.

Atkinson and Marlier (2010) acknowledged that their concrete proposal for an EU Basic Income for Children was explicitly modelled in a study by Levy, Lietz and Sutherland (2007), using the EU tax-benefit model EUROMOD. As the authors of that study had explained (Levy et al., 2006; 2007):

“A pure child basic income would consist of a generous unconditional child payment that would replace all existing child contingent tax concessions and cash transfers. A variation of this form of CBI could involve the setting of a universal level of child minimum income that would be unconditionally guaranteed to every child. Under the principle of subsidiarity, each Member State could choose its own preferred method to deliver this basic income.”

In general, there are three broad ways to think about the introduction of an EU-wide Child Basic Income (CBI) scheme in practical terms. Two were just mentioned above: the first would be a “replacement” scheme introduced at EU level at the same time as all provision for children currently existing at national level is abolished; the second would be a “top-up” scheme, with the EU supplementing national provision in cases where it falls below the universal level guaranteed.

Our paper updates the study of Levy et al. (2007) and extends it to cover the EU27 and by assessing the effects of a third variant: an “additional” scheme that would pay the same amount for all eligible children in the EU, either in absolute or in relative (i.e. purchasing power) terms.

Obviously, an “additional” scheme would be vulnerable to the familiar charge that it looks like a free lunch, and a very expensive free lunch at that. To address that charge, we have limited eligibility for the EU Child Basic Income to children aged under 6. In addition to fiscal concerns, the narrow age focus might also be justified by the innovative character of the policy, which requires some caution. Moreover, as is standard practice with child benefits in Britain and elsewhere, the EU Child Basic Income simulated here is paid to the mother. Also, crucially, it is assumed to be taxed as income – again, as is standard practice with universal benefits, e.g. in Scandinavia. Since it is paid to the mother it is assumed to be taxed as her income. While national taxation would “claw back” some of the fiscal spending on the scheme, its net cost would remain considerable. In view of that, and in line with Atkinson (1995), we have assumed that the scheme would be funded out of a flat tax on all incomes, at a common rate set exactly to offset its net cost at EU level. Finally, as explained above, the benefit would be universal, i.e. paid irrespective of parents’ income.

More specifically, for illustrative purposes the benefit rate is set at €50 per month per child,2 first in absolute terms (i.e. at the same benefit rate in all member states) and then in purchasing power parity terms (i.e. adjusting the benefit rate so as to reflect price differences between member states) respectively. The first of these naturally distributes more resources to children in lower-income countries than does the price-adjusted scheme.

This paper estimates the cost of each version (in each member state and in the EU as a whole), its impact on poverty among the children targeted by the scheme (also in each member state and in the EU as a whole), and fiscal flows between member states (resulting from the fact that the flat tax is set at a common rate, which is set to offset the net cost of CBI at EU – not national – level).

2. Methodology

2.1 EUROMOD

We make use of EUROMOD, the tax-benefit microsimulation model for the European Union.3 Using household micro-data representative of the population of each EU member state, EUROMOD computes tax liabilities and benefit entitlements for all observations in the database. Based on a common framework – which applies the same methods and approaches both in the construction of the databases and in the calculation of taxes and benefits of each country – EUROMOD is a unique tool for international comparative research on the effects of taxes and benefits, and their reforms, on the distribution and redistribution of income. The analysis in this paper demonstrates how EUROMOD can be used to explore the between-country effects of EU-level policies, as well as to compare the within-country consequences.

2.2 Data

In most cases the national databases used in EUROMOD are drawn from the European Union Survey on Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC), provided by Eurostat. In some of countries national versions of the EU-SILC – provided by national statistics institutes – complement or substitute for the Eurostat data (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Greece, Spain, Italy, Luxembourg, Austria, Poland and Slovakia). In the case of the United Kingdom, data from the Family Resources Survey are used instead.

In this analysis the data are those collected in the year 2008 with income information referring to the previous year, with the exception of France (data collected in 2007), Malta (data collected in 2009) and the UK (data collected in 2008/2009 and income referring to the previous month)4.

2.3 Simulation

We explore the effects of the CBI as if it were introduced into the 2010 tax-benefit systems. We would not generally expect to see much difference in effects if another policy year was used as the base. In order to do this, monetary variables in the data are brought to 2010 levels by applying updating indices that reflect the average evolution of these variables between the income reference period (2007 in most countries) and the year of simulation (2010).

The reform scenario consists of a CBI paid per child under 6 years of age. The amounts of benefit are the same for all children, independently of family circumstances or the receipt of any other benefit. In all countries and independently of the approach to similar benefits, the CBI is assumed to be paid to the mother and is made subject to income tax on the same basis as her employment earnings.5 The reform is made budget neutral by introducing an EU flat tax. This is levied on all gross income (defined as all market and other original income, pensions and state benefits, before the deduction of income taxes and social contributions) at the same rate across the EU. It raises sufficient revenue at EU level to meet the aggregate ‘net cost’ of the benefit (i.e. after it is taxed at the national level).6

The rate of EU flat tax needed to pay for the CBI set at €50 per month per child is about 0.2%. We explore the effects of two variants, one which sets the level at €50 in cash terms everywhere, and another which adjusts the €50 for PPP differences, reducing the amount of between country redistribution. As shown in Table 1, once adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) the CBI rate per child varies significantly, from €25.40 in Bulgaria to €71.15 in Denmark.

Child Basic Incomes: target populations and benefit amounts.

| Share of children aged below 6 in the population (2010) (%) | PPP-adjusted €50 EU CBI (€ per month per child) | |

|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 6.9 | 55.70 |

| Bulgaria | 5.8 | 25.40 |

| Czech Republic | 6.3 | 37.60 |

| Denmark | 7.1 | 71.15 |

| Germany | 5.0 | 52.15 |

| Estonia | 6.7 | 37.40 |

| Ireland | 9.3 | 59.55 |

| Greece | 6.0 | 47.55 |

| Spain | 6.4 | 48.50 |

| France | 7.4 | 55.40 |

| Italy | 5.7 | 51.75 |

| Cyprus | 6.7 | 44.55 |

| Latvia | 6.0 | 36.10 |

| Lithuania | 5.8 | 32.55 |

| Luxembourg | 6.9 | 60.25 |

| Hungary | 5.8 | 32.45 |

| Malta | 5.8 | 38.95 |

| Netherlands | 6.7 | 53.80 |

| Austria | 5.7 | 53.10 |

| Poland | 6.0 | 30.95 |

| Portugal | 5.9 | 44.10 |

| Romania | 6.1 | 29.40 |

| Slovenia | 5.9 | 42.30 |

| Slovakia | 6.1 | 35.80 |

| Finland | 6.7 | 61.75 |

| Sweden | 7.0 | 60.80 |

| United Kingdom | 7.3 | 50.10 |

-

Notes: “PPP-adjusted €50 EU CBI” is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month, adjusted for power purchasing parity, to all children below the age of 6 in the EU.

-

Sources: Own calculations based on Eurostat (2012) Purchasing power parities, http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/purchasing_power_parities/data/database, Population by age in 2010: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/population/data/database. Downloaded on 10 Feb 2012 15:45:33 MET.

2.4 Measurement

Following the fact that the policy analysed here is targeted at those under the age of 6, all indicators are based on the same age group. In this analysis we assume that income is equally shared within the household, so that household disposable income can be used as an indicator of the economic well-being of each individual within the household (‘within household’ incidence is not considered).

Household disposable income is defined as market income plus private transfers and social benefits minus taxes and social contributions, aggregated at the household level. Non-cash benefits are not included. Household disposable incomes are equivalised using the modified OECD equivalence scale.

Following the Laeken approach, the at-risk-of-poverty rate is defined as the proportion of population living in households with equivalised household disposable income below 60 (or 40) per cent of the median. In assessing changes in poverty due to the scheme, the poverty threshold is held fixed at its pre-reform (baseline) level. This is done in order to distinguish the effects of the scheme on young children’s material standards relative to the current situation, from those of movements in the poverty threshold as a result of changes in median incomes.

3. Results

3.1 Cost of an EU CBI

The gross cost of a Child Basic Income for the European Union would obviously depend on the benefit rate. The CBI scheme modelled here paying €50 per month per child would cost around €18 billion EU-wide, i.e. 13% of the current EU budget, or 0.15% of the European Union’s GDP, as shown in Table 2.

Funding implications at EU level.

| EU CBI scheme | ||

|---|---|---|

| 50abs | 50ppp | |

| gross cost (million euro per year) | 18,302 | 17,928 |

| as % of EU budget | 12.98% | 12.72% |

| as % of EU GDP | 0.15% | 0.15% |

| national tax levied (million euro per year) | 2,740 | 2,760 |

| as % of gross cost | 14.97% | 15.39% |

| EU tax required (million euro per year) | 15,393 | 14,976 |

| flat tax rate | 0.204% | 0.198% |

| as % of EU budget | 10.92% | 10.62% |

| as % of EU GDP | 0.13% | 0.12% |

-

Notes: ‘50abs’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month. ‘50ppp’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month adjusted for power purchasing parity. All children below the age of 6 in the EU would be eligible under both schemes.

Sources: Own calculations based on EUROMOD F5.36.

Making the CBI taxable at national level as the income of the mother would ‘claw back’ about 15% of its total gross cost. The rest would be funded by a flat tax on all incomes, set at a common rate of about 0.2% across the EU. The gross and net costs, and revenue-neutral tax rate are slightly lower in the case of the PPP-adjusted scheme (“50ppp” in the figures and tables) than for the scheme which gives €50 in absolute terms to each child (“50abs”).

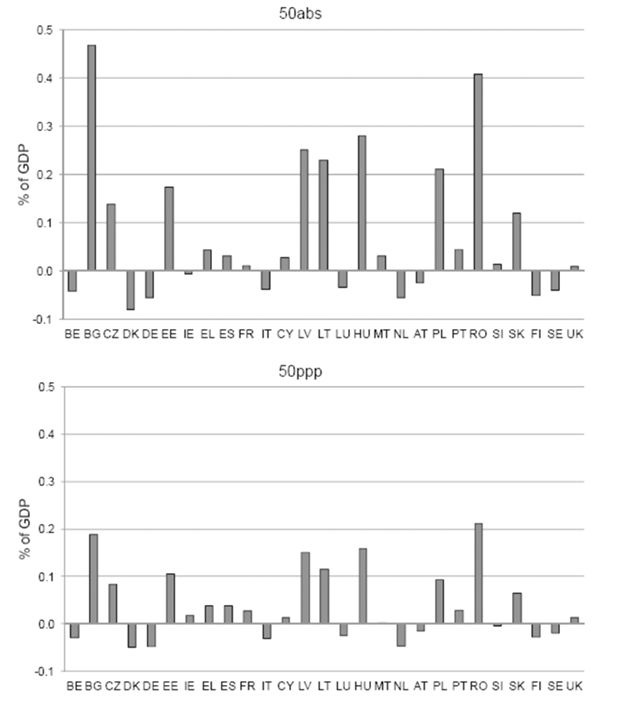

For the EU as a whole, the gross cost of CBI is fully financed by the sum of the additional yield of national taxes and the EU flat tax. However, across countries, the relative size of gross cost, the amount collected through national tax, and the amount collected through the EU flat tax each vary greatly. They also depend on whether the CBI has been adjusted for purchasing power differences. Figure 1 shows these variations with the components measured as percentages of GDP.

Cost and funding implications by country.

Notes: ‘50abs’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month. ‘50ppp’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month adjusted for power purchasing parity. All children below the age of 6 in the EU would be eligible under both schemes. As % of national GDP.

Sources: Own calculations based on EUROMOD F5.36.

In this sense, the gross cost (as a proportion of national GDP) of a European CBI set at the same absolute level in each country (50abs) is greatest in Bulgaria and Romania, followed by Hungary, Poland and the Baltic states. The proportion of total gross cost ‘clawed back’ through national taxation would vary widely across countries, from under 5% in the Czech Republic and Slovakia to over 30% in Belgium and the Nordic countries. Such differences reflect both differences in income taxation regimes and in the labour market participation of mothers with young children (since the CBI is assumed to be taxed as the mother’s income and the size of the CBI is not itself generally sufficient to bring mothers without other incomes into income taxation). The amount of EU flat tax contributed by the country to the EU “pot” depends solely on aggregate gross income in the country. The relationship between total personal gross income as measured by a household survey and GDP as measured in National Accounts is not the same across countries. This explains why the flat tax revenue, as a percentage of GDP, shown in Figure 1 ranges from 0.07% in Romania, Hungary and Luxembourg to 0.14% in Denmark, Germany, Italy, Cyprus and the UK.

Clearly, variation between member states in the gross cost is much less if the CBI is adjusted for purchasing power parity (‘50ppp’) than if it is set in absolute terms. This means that there is also less variation in the national tax collected. The total EU tax revenue from each member state is much the same in both versions of the scheme.

3.2 Fiscal flows between and within member states

The information in Figure 1 implies that the scheme would involve significant redistribution between countries. Richer countries and/or those with fewer young children per income earner are likely to be net contributors. Poorer countries and/or those with more young children are likely to be net beneficiaries. This can be seen more directly from Figure 2 which shows the net gain or loss by country as a percentage of GDP.

Net flows as a percentage of national GDP.

Notes: ‘50abs’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month. ‘50ppp’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month adjusted for power purchasing parity. All children below the age of 6 in the EU would be eligible under both schemes.

Sources: Own calculations based on EUROMOD F5.36.

The main net gainers from a CBI that is set in absolute terms would be (in order of magnitude relative to GDP) Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Poland, the Baltic countries, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. The South European countries (except Italy), France, Cyprus, Malta, Slovenia and the UK (the latter two marginally) would also benefit.

On the other hand, no member state would have to pay in flat tax more than 0.1% of its GDP in excess of what it would receive in CBI. The main net contributors (relative to their own GDP) would be Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Finland, Sweden and Belgium, followed by Austria, Italy, Ireland and Luxembourg.

The ordering of countries is similar in the case of the CBI adjusted for purchasing power parity, but the scale of losses, and especially gains, is smaller.

In terms of the absolute amount of budget required as net contribution, the five countries contributing the most to the scheme are (in order) Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Denmark and Belgium. As indicated by the value of the PPP-adjusted CBI in Table 1, these are all relatively high income countries,7 but they are not necessarily large. The five countries receiving the most are, for the unadjusted CBI, (in order) Poland, Romania, Spain, Hungary and the Czech Republic. For the ppp-adjusted CBI, the group of countries gaining the most in transfer from the others includes (in order) France, Spain, Poland, Romania and the UK. Once differences in price and income levels have been (approximately) accounted for by the ppp adjustment, the large gainers include countries such as France and the UK, in both cases collecting relatively little national tax on the CBI (see Figure 1) and with higher than average shares of young children in their populations (see Table 1). Germany and Italy are major net contributors in part because they have relatively few young children in their populations.

Within countries there is redistribution from households without young children to those with young children. While all the former are contributors to the scheme, virtually all of the latter are net beneficiaries, paying less in additional tax than they receive in CBI. Under the unadjusted scheme, only 0.4% of all children aged below 6 in the EU are in a household experiencing a net income loss. Even in Denmark, the country where that proportion is largest, fewer than 2% lose.8

3.3 Impact on child poverty

We estimate child poverty in the EU in the absence of an EU CBI (i.e. in the baseline), relative to a poverty threshold at 60% of national equivalised median income, in the 0-5 age group, to be 17.0%. Compared to that baseline, and using a fixed poverty line, Table 3 shows that the unadjusted EU CBI would reduce the headcount rate by 14.2% and reduce the poverty gap (i.e. the average income shortfall of families with young children relative to the poverty line) by 6.2%.

Impact on child poverty in the EU.

| EU CBI scheme | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 abs | 50ppp | |||

| A. poverty line fixed to the baseline at 60% of equivalised median disposable income | ||||

| Headcount rate | ||||

| Baseline (without EU CBI) | 17.0% | |||

| Reform (with EU CBI) | 14.6% | 14.9% | ||

| Difference in percentage points | −2.4 | −2.2 | ||

| Proportional reduction (%) | Poverty gap | 14.2 | 12.7 | |

| Baseline (without EU CBI) | 26.5% | |||

| Reform (with EU CBI) | 24.9% | 25.2% | ||

| Difference in percentage points | −1.6 | −1.1 | ||

| Proportional reduction (%) | 6.2 | 4.3 | ||

| B. poverty line fixed to the baseline at 40% of equivalised median disposable income | ||||

| Headcount rate | ||||

| Baseline (without EU CBI) | 5.4% | |||

| Reform (with EU CBI) | 4.3% | 4.5% | ||

| Difference in percentage points | −1.1 | −0.9 | ||

| Proportional reduction (%) | Poverty gap | 20.8 | 16.7 | |

| Baseline (without EU CBI) | 31.7% | |||

| Reform (with EU CBI) | 29.3% | 29.8% | ||

| Difference in percentage points | −2.4 | −2.1 | ||

| Proportional reduction (%) | 7.7 | 6.6 | ||

-

Notes: ‘50abs’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month. ‘50ppp’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month adjusted for power purchasing parity. All children below the age of 6 in the EU would be eligible under both schemes. Poverty indices are computed for the population of children under 6 years of age. The EU poverty rate is calculated by adding up the number of such children calculated to be below the national poverty thresholds in each country and dividing by the EU population of children in this age group.

-

Sources: Own calculations based on EUROMOD F5.36.

The ppp-adjusted CBI would reduce poverty among younger children by somewhat less: the headcount rate by 12.7% and the poverty gap by 4.3%.

The anti-poverty effect of a EU CBI using a lower threshold, at 40% of median income, would be stronger in the sense that a higher proportion of a smaller group would be taken out of poverty. In terms of headcount rates, from a baseline of 5.4%, poverty would fall by 1.1 percentage points (for the flat rate CBI), i.e. by one fifth. Moreover, the reduction in poverty gap (i.e. the average income shortfall of the relevant families), relative to the income corresponding to a poverty line at 40% of median, would be 2.4 percentage points, the proportional reduction being 7.7% (under ‘50abs’). The EU-level reductions under the ppp-adjusted CBI are again smaller.

Table 4 shows the proportional reduction in the number of children aged below 6 in poverty achieved by the EU CBI on a country-by-country basis. Focusing on the best-performing version (€50 per month for each eligible child), the reduction would be greatest in Hungary (37%), and exceed 25% in Romania, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Estonia, Lithuania and the Czech Republic; in contrast, it would be negligible in Sweden and Denmark (1% or less).

Impact on child poverty per country (children under 6 years of age).

| Baseline poverty rate (%) | Poverty rate after the reform (%) | Proportional reduction in poverty (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50abs | 50pps | 50abs | 50pps | ||

| Belgium | 12.2 | 10.0 | 9.8 | −18 | −20 |

| Bulgaria | 26.1 | 18.1 | 21.8 | −31 | −16 |

| Czech Republic | 9.6 | 7.2 | 7.6 | −25 | −21 |

| Denmark | 6.9 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 0 | −1 |

| Germany | 14.2 | 12.8 | 12.5 | −10 | −12 |

| Estonia | 13.7 | 9.9 | 10.9 | −27 | −20 |

| Ireland | 14.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | −7 | −7 |

| Greece | 20.4 | 18.1 | 18.5 | −12 | −10 |

| Spain | 17.0 | 15.5 | 15.5 | −9 | −9 |

| France | 16.6 | 15.4 | 15.0 | −7 | −9 |

| Italy | 20.2 | 18.4 | 18.4 | −9 | −9 |

| Cyprus | 13.1 | 9.9 | 9.9 | −25 | −25 |

| Latvia | 21.4 | 17.0 | 18.6 | −20 | −13 |

| Lithuania | 15.8 | 11.6 | 13.4 | −27 | −15 |

| Luxembourg | 9.4 | 7.5 | 7.2 | −20 | −23 |

| Hungary | 18.0 | 11.4 | 12.9 | −37 | −28 |

| Malta | 18.3 | 14.9 | 15.9 | −19 | −13 |

| Netherlands | 11.7 | 10.1 | 9.2 | −14 | −22 |

| Austria | 13.7 | 11.0 | 11.0 | −20 | −20 |

| Poland | 18.5 | 14.3 | 15.5 | −23 | −16 |

| Portugal | 15.1 | 11.7 | 12.9 | −23 | −15 |

| Romania | 26.2 | 16.9 | 21.3 | −35 | −19 |

| Slovenia | 11.1 | 9.4 | 9.5 | −15 | −15 |

| Slovakia | 13.8 | 9.6 | 11.2 | −30 | −19 |

| Finland | 12.4 | 10.7 | 10.2 | −14 | −18 |

| Sweden | 12.1 | 11.9 | 11.8 | −1 | −2 |

| United Kingdom | 19.7 | 17.3 | 17.3 | −12 | −12 |

-

Notes: ‘50abs’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month. ‘50ppp’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month adjusted for power purchasing parity. All children below the age of 6 in the EU would be eligible under both schemes. Poverty rate of children under 6 years of age. The poverty line defined as 60% of national equivalised median disposable income in the baseline.

-

Sources: Own calculations based on EUROMOD F5.36.

On the other hand, if the level of payment were adjusted for purchasing power parity, the poverty reduction would also be significant in Western Europe, especially but not exclusively in Finland, Austria and the Netherlands (a reduction of 18%, 20% and 22% respectively). Since poverty status depends on household income, the reduction in poverty achieved for young children also applies to their older (co-resident) siblings and parents, as well as any other household members. The reduction in poverty rates due to the EU CBI for the population as a whole (again, on a country-by-country basis and at the EU level as well) is shown in Table 5. The proportional reduction is naturally lower but under ‘50abs’: it reaches 2% in the EU as a whole (1.5 million people), and is as large as 8% in Hungary, and around 5% in Romania and Slovakia.

Impact on overall poverty per country.

| Baseline poverty rate (%) | Proportional reduction in overall poverty (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 50abs | 50pps | ||

| EU | 15.9 | −2 | −2 |

| Belgium | 11.6 | −2 | −2 |

| Bulgaria | 20.0 | −4 | −2 |

| Czech Republic | 7.9 | −2 | −1 |

| Denmark | 10.4 | 2 | 3 |

| Germany | 14.2 | −1 | −1 |

| Estonia | 15.6 | −3 | −3 |

| Ireland | 13.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Greece | 20.8 | 0 | 0 |

| Spain | 18.8 | −1 | −1 |

| France | 13.3 | −1 | −2 |

| Italy | 17.5 | −1 | −1 |

| Cyprus | 14.6 | −3 | −3 |

| Latvia | 20.1 | −1 | −1 |

| Lithuania | 17.8 | −1 | 0 |

| Luxembourg | 8.2 | −3 | −3 |

| Hungary | 11.3 | −8 | −7 |

| Malta | 16.1 | −2 | −1 |

| Netherlands | 10.2 | −2 | −3 |

| Austria | 11.8 | −3 | −2 |

| Poland | 17.5 | −2 | −1 |

| Portugal | 19.1 | −3 | −2 |

| Romania | 23.1 | −5 | −3 |

| Slovenia | 13.7 | −2 | −2 |

| Slovakia | 9.4 | −5 | −4 |

| Finland | 11.9 | −2 | −2 |

| Sweden | 12.4 | 1 | 1 |

| United Kingdom | 16.3 | −2 | −2 |

-

Notes: ‘50abs’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month. ‘50ppp’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month adjusted for power purchasing parity. All children below the age of 6 in the EU would be eligible under both schemes. Poverty rate of total population. The poverty line defined as 60% of national equivalised median disposable income in the baseline.

-

Sources: Own calculations based on EUROMOD F5.36.

3.4 Vertical and horizontal redistribution

At this point, an interesting question arises: how would the net monetary advantage of an EU CBI be distributed vertically (i.e. between income groups) given the horizontal distribution that we have seen from households without young children to those with them. The answer to that question is not obvious because the EU CBI would be funded out of a combination of national (often progressive) and European (flat rate) taxation, and would target a particular group: children aged 0-5.

In terms of vertical redistribution, Figure 3 clearly shows that among those with eligible children (i.e., aged 0 to 5) the net value of the EU CBI (once taxes have been paid) would be worth more in cash terms to low-income households than to high-income households.

Net average benefit per child by income quartile group in euro per month.

Notes: ‘50abs’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month. ‘50ppp’ is a Child Basic Income scheme that pays €50 per month adjusted for power purchasing parity. All children below the age of 6 in the EU would be eligible under both schemes. Euro per child per month. Average benefit is net of national and EU taxes; q1 = poorest 25%; q4 = the richest 25% of the distribution of equivalised household disposable income (for children aged under 6 only).

Sources: Own calculations based on EUROMOD F5.36.

Among these households, under the unadjusted EU CBI (‘50abs’), those in the bottom 25% of the income distribution would in most countries gain over €40 per month per eligible child (the remainder being taxed away). Even in net contributor countries, low-income families with eligible children would gain considerable amounts: on average €43 per month per child in Germany, €31 in the Netherlands, €23 in Denmark.

On the other hand, children in the top 25% would benefit less, especially in countries with progressive income tax schedules. Even so, their net gain would in many countries exceed €25 per eligible child per month. In countries where national taxes are high (so that a high share of benefit would be clawed back in national tax), and where incomes are high (so that the EU flat tax would bite more in absolute terms) the gains are lower: in Germany their net gain would be €20 per month on average per child, in the Netherlands €16, in Denmark and Luxembourg €10.

In some countries (e.g. Bulgaria and Lithuania) there is little variation in gain by income, reflecting a combination of high levels of maternal employment and flat income tax schedules.

With ppp-adjustment, gains can exceed €50 per child and this happens on average in the bottom quartile group in Ireland, France and Luxembourg. The pattern of gain across the income distribution is similar to that under the unadjusted scheme in each country, even if the average effect differs.

Further analysis confirms that the distributional impact of this EU CBI scheme would also be progressive when the entire EU population9 is considered. For instance, an unadjusted EU CBI of €50 per month, would, on average, increase the income of those in the bottom quartile group of the EU income distribution by €1.95 per month and of those in the second quartile group by €1.52. In contrast, those in the third quartile group would lose €0.04 per month, while the top 25% would lose €3.42 per month.

4. Conclusions

This paper assesses the likely effects of an EU Child Basic Income for young children in terms of poverty reduction and fiscal costs, including flows between member states. In doing so it demonstrates how EUROMOD can be used to analyse the between-country effects of EU-level policies, as well as to compare the within-country consequences.

According to our simulations, the gross cost of such a scheme set at €50 per month per child aged under 6 would be around 0.15% of EU GDP. National taxation could be used to claw back one-seventh of that cost on average and the remainder could be financed by a flat tax on all gross household income of about 0.20%.

The anti-poverty impact of such a scheme would be quite significant, reducing the risk of poverty among young children by 14% (800 thousand children) and closing the poverty gap of those remaining below the threshold by 6%.

Within countries, the scheme would distribute income to households with young children from households without them. Between countries, the scheme would redistribute income away from richer member states with fewer children towards poorer ones with more children. Most member states and virtually all children aged under 6 would be net gainers. In general, fiscal flows between member states, and also poverty reduction, would be greater under the EU CBI set in absolute terms rather than PPP-adjusted. On the whole, no member state would have to pay in flat tax more than 0.1% of its GDP in excess of what it would receive in CBI.

The implications of the particular scheme that we have analysed (additional to the existing system, financed by an EU flat tax) can be generalised or extrapolated to other CBI schemes with the same basic characteristics. For example, Levy et al. (2012) also explored a €20 scheme, and suggested a rule of thumb that an additional EU flat tax rate of 0.004% would be needed for each additional euro of CBI per month. Extending the CBI to cover all children under 16 would cost about three times as much in gross terms and might require an EU tax of somewhat less than three times that considered here (to the extent that the national tax collected from the mothers of older children might be greater). Generally, the between country redistribution seen here would have a similar pattern under more ambitious CBI schemes, on a larger scale.

This exercise has also suggested ways in which a European CBI scheme might be improved. Taxing the CBI as the mother’s income has attractions on vertical equity grounds and as a way of minimising the EU tax needed. But our results show that countries with already high taxes also tend to be net contributors. To the extent that these are also countries already with substantial provision for children (Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark) this might erode support for an EU CBI. Therefore, in high tax countries, relying fully on an EU flat tax to finance a European CBI scheme might be more attractive.

The version of an EU Child Basic Income for young children discussed in this paper is put forward mainly for illustrative purposes. We do not wish necessarily to recommend “our” version over alternative ones. For instance, the more flexible blueprint of Atkinson and Marlier (2010) for an EU-mandated (but nationally-funded) EU Basic Income for Children, and the proposal of Levy et al. (2007) for a “top-up” scheme (under which the EU CBI would supplement national provision when it falls below the guaranteed level), briefly discussed earlier, both deserve greater attention than they have received so far.

Having said that, we need to recognise the main advantage of an “additional” scheme discussed here relative to a “top-up” one is that the former would be less vulnerable to moral hazard. Under the latter version, national governments would have a perverse incentive to reduce national provision so as to maximise the amount of the transfer from the EU.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that the potential for strategic manipulation may also be present in a milder form under the version analysed here. With an “additional” scheme, governments might decide that the amount of benefit paid to families with young children through national arrangements is already “sufficient”, and hence reduce it by the amount of the additional CBI. In this case, moral hazard would obviously have an impact on the total amount of income support to families with young children, but at least would not affect the level of transfers between countries.

On the whole, a considerable amount of jostling for position between the various tiers of policy-making (the EU, national governments and even local governments, where applicable) seems inevitable. In view of that, setting a modest EU-wide floor, funded out of the EU budget, then allowing member states (or regional administrations) wishing to aim higher to pay for the extra cost out of their own budgets, can be seen as a rather sensible solution.

As shown in our paper, the cost of an EU CBI need not be prohibitive. But can such a scheme ever be feasible politically? The idea that relatively low-income households in rich countries should contribute to supporting young children in relatively high-income households in poorer countries might seem far-fetched, particularly given that one of the side effects of the current crisis has been a reduction in feelings of solidarity across member states among EU citizens.10

By the same token, European statesmen and women willing to embark on the long trek towards (re)building a shared European identity, cannot hope to find a better starting point than a scheme supporting the incomes of families with young children, wherever in the EU they might reside. As the European Commission document cited earlier put it, such a scheme “could be a demonstration of the EU’s commitment to children, to the future” (European Commission 2012a: 62).

Footnotes

1.

The views expressed in this paper do not represent the official positions of the OECD or the governments of OECD member countries.

2.

Levy et al. (2012) also consider a lower level payment set at €20 per month per child.

3.

4.

For more information about the country-specific implementation, see the EUROMOD Country Reports at https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/euromod/resources-for-euromod-users/country-reports

5.

In the case of France, the benefit is also assumed to be subject to Contribution Sociale Généralisée (CSG) on the basis that French taxable benefits are also liable for this charge.

6.

We assume that there is no evasion of either the national or EU tax and that the CBI is fully taken up. We assume no behavioural reactions to the policy reform that would affect its cost or distributional effect.

7.

High values indicate relatively high price levels and suggest relatively high average incomes.

8.

Note that under the ppp-adjusted scheme the number of net losers is smaller.

9.

Ranking by equivalised household income, not adjusted for purchasing power differences.

10.

Evidence from Eurobarometer surveys shows that throughout Europe trust in the European Union has declined from 57% in May 2007 to 48% in November 2009 and to 31% in May 2012. See Standard Eurobarometer 77 “Public opinion in the European Union” Spring 2012 (http:/ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb77/eb77_anx_en.pdf) and previous waves The figures cited here are positive responses to Q44b: “I would like to ask you a question about how much trust you have in certain institutions. For each of the following institutions, please tell me if you tend to trust it or tend not to trust it? (The European Union)”.

References

- 1

-

2

Public Economics in Action: The Basic Income/Flat Tax ProposalOxford: Clarendon Press.

-

3

A comparison of child benefit packages in 22 countriesResearch Report No 174London: Department for Work and Pensions.

-

4

EU Employment and Social Situation Quarterly ReviewBrussels: The European Commission.

- 5

- 6

-

7

Social policies, family types and child outcomes in selected OECD countries. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper 6Paris: OECD.

-

8

A Basic Income for Europe’s children?. EUROMOD Working Paper EM4/06Colchester: ISER, University of Essex.

-

9

Inequality and Poverty Re-examinedA guaranteed income for Europe’s children?, (Eds.), Inequality and Poverty Re-examined, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

-

10

The distributive and cross country effects of a Child Basic Income for the European UnionResearch Note 2/2012 of the European Observatory on the Social Situation and Demography.

-

11

http://www.missoc.org/MISSOC/comparativeTablesComparative tables on social protection. The EU’s Mutual Information System on Social Protection.

-

12

Modelling Our Future: population ageing, health and aged careEUROMOD: the tax-benefit microsimulation model for the European Union, (Eds.), Modelling Our Future: population ageing, health and aged care, International Symposia in Economic Theory and Econometrics, 16, Elsevier.

-

13

EUROMOD: the European Union tax-benefit microsimulation modelThe International Journal of Microsimulation 6:4–26.

-

14

Child benefit reform and labor market participationJournal of Economics and Statistics 230:313–327.

Article and author information

Author details

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank participants at the 2nd Essex Microsimulation Research Workshop, the editors and a referee for helpful comments. We are also grateful for support from the Social Situation Observatory (SSO) Network on Income and Living Conditions (http://www.socialsituation.eu/). A preliminary version of this analysis is published as SSO Research Note 2/2012. We also acknowledge the contribution of all past and current members of the EUROMOD consortium. The process of extending and updating EUROMOD is financially supported by the Directorate General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion of the European Commission [Progress grant no. VS/2011/0445]. We make use of EUROMOD F5.36 and microdata from the EU Statistics on Incomes and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) made available by Eurostat under contract EU-SILC/2011/55; national EU-SILC “PDB” data made available by the national statistical offices of Austria, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Slovakia and Spain. For the UK, the Family Resources Survey data are made available by the Department of Work and Pensions via the UK Data Archive. The authors alone are responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the data reported here.

Publication history

- Version of Record published: April 30, 2013 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2013, Levy et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.