What happened to the ‘Great American Jobs Machine’?

- Article

- Figures and data

- Jump to

Abstract

In the 1980s and 1990s the US employment rate increased steadily, and by 2000 it was one of the highest among the rich democratic nations. Since then it has declined both in absolute terms and relative to other countries. We use an in-depth comparison between the United States and the United Kingdom to probe the causes of America’s poor recent performance. Contrary to a common narrative, a comparative perspective suggests that the decline in US labour force participation is not confined to the (white) male population; the divergence in the female participation rate is even more pronounced. We do not find evidence that the poor US performance is linked to cyclical patterns, such as the 2008–09 Great Recession; instead, it is a more pervasive, longer-run phenomenon. The relative decline of US participation rates compared to the UK is attributable to shifts in socio-demographic characteristics, such as education, and to shifts in the impact of those characteristics, which have become more adverse to participation.

1. Introduction

Labour force participation in the United States increased steadily in the 1980s and 1990s. However, it declined between 2000 and 2007 and then fell even more sharply in the Great Recession. Macroeconomic recovery saw unemployment fall rapidly from 2011, but the participation rate has only increased modestly, remaining well below its pre-crisis level and even further below its late-1990s peak. An expanding research literature has advanced a range of explanations for this dramatic reversal in what not long ago was known as the ‘great American jobs machine’ (The Economist, 2000).

The US experience since 2000 contrasts sharply with what has happened in the United Kingdom. There, labour force participation was fairly stable in the decade up to the onset of the Great Recession, fell by much less during the crisis, and since 2012 has been rising significantly. These two countries have many features in common, including deregulated labour markets and independent currencies. And both had a comparatively high participation rate at the end of the 1990s. Given the divergence in participation rates since 2000 and through the crisis and recovery periods, comparison of these two cases can provide a helpful perspective on the US story. We exploit this comparative potential, analysing the two countries’ experiences over recent decades through a common analytical lens and assessing hypotheses about key drivers of stagnant labour force participation in the US in that light.

We focus on three questions: Does the gap between the two countries lie mainly with men or women? How much of the gap is a product of structural factors as opposed to cyclical ones? And how much do structural shifts reflect changes in composition as opposed to changes in behaviours?

We find that male labour force participation rates are trending downwards in both countries, but the trend is stronger in the US. Female participation is also a major part of the story, with rates for later cohorts trending upward in the UK while downward in the US. Structural shifts have been more important than cyclical patterns. The ageing of the baby boom generation has a greater impact in the US than the UK, because participation rates decline with age more steeply in the US and its baby boom generation was a relatively high-participation generation. Alongside compositional change, aspects of behaviour of the US population have become comparatively less favourable to participation. There was little difference in participation between the two countries in the decade from the mid-1990s because composition and behavioural differences roughly offset one another. The marked gap observed more recently, by contrast, reflects both composition differences and behaviour becoming less favourable to participation in the US compared with the UK.

Section two describes trends in labour force participation, employment, and unemployment rates in the two countries over recent decades. Section three reviews existing explanations for these trends. Section four outlines our empirical strategy, and section five presents the results. Section six sets the findings from our US-UK comparison in broader comparative context.

2. Recent trends in labour force participation and employment

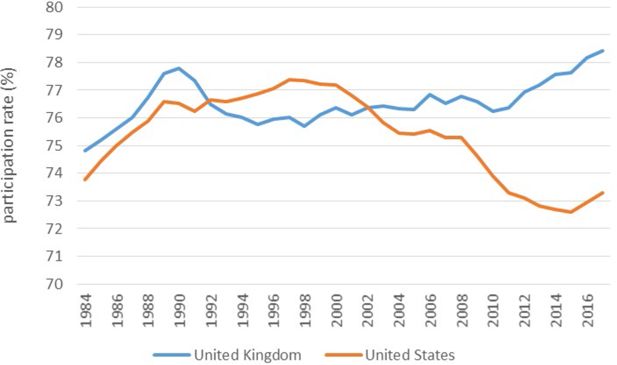

Figure 1 shows the labour force participation rate — the share of the working-age population, defined as ages 15–64, who are either in paid work or unemployed — in the US and the UK since 1984. (We take 1984 as initial year at this point for data comparability reasons.) Up to the early 1990s, both countries saw substantial increases in the participation rate, with the UK rate about one percentage point higher and peaking at almost 78% in 1990. The UK level then dipped in the early 1990s and remained at about 76% to 2000., whereas in the US the participation rate rose to reach 77.5% in the ‘Clinton boom’ of the second half of the 1990s, and was still at that peak entering 2000.

However, the US rate then declined to about 75% in the years up to the 2008–09 global financial crisis, before falling much more sharply during and after the Great Recession to hit a low of 72% in 2015. Recovery since that low point has been modest, with the participation rate in late 2017 only 73%. In the UK, on the other hand, the participation rate remained at about 76%–77% up to the onset of the Great Recession, did not fall below 76% even in the depths of the crisis, and bounced back quite quickly so that by late 2017 it was approaching 79%. The gap between the two countries in 2017 was six percentage points.

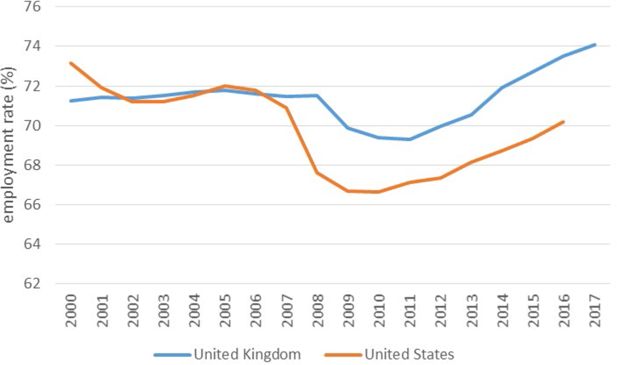

The business cycle dynamics of the two countries in terms of unemployment are rather similar since 2000, fluctuating more in the US up to and through the crisis but then converging. The major differences in participation rates between the two countries since 2000 are to be seen not in their unemployment experiences but with respect to employment versus inactivity. Figure 2 shows that the UK employment rate was stable at about 71% from 2000 up to the Great Recession, and then fell by more than two percentage points before recovering from 2012 to now reach 74%. In the US, by contrast, the employment rate declined quite sharply in the early 2000s, then fell by almost five percentage points during the early years of the crisis, twice as much as in the UK. While employment picked up from 2012 onwards, by 2017 it was still only about 70%, compared to 72% in 2007. Having been nearly three percentage points higher than the UK in 2000, this left the US employment rate four percentage points below the UK in 2017. So from 2000 to the present, the share of the working-age population in paid work in the US contracted, and the percentage inactive expanded, by about four percentage points. Over the same period, the percentage at work in the UK rose by two percentage points. This is the key difference underlying the contrasting evolution of their labour force participation rates.

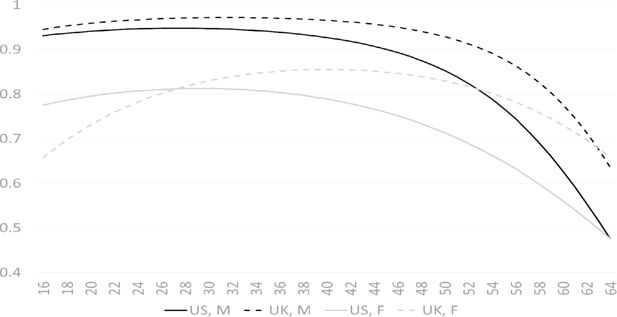

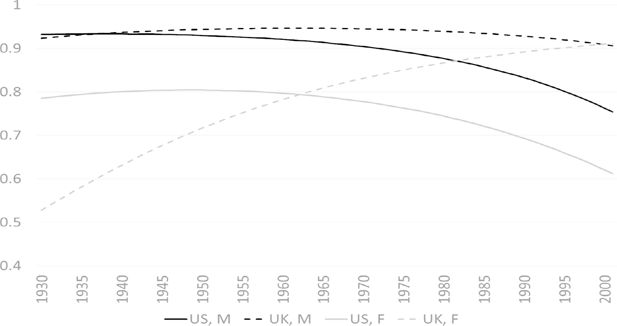

The falling participation rate in the US is often discussed as mainly relating to men (eg, Eberstadt, 2016), or even as concentrated among middle-aged men. However, the comparative patterns for the participation rate since 1984 disaggregated by gender and age group, shown in Figure 3 for men and Figure 4 for women, tell a different story. They show participation rates in the US from 2000 falling substantially for men in each age group up to 54, with those over 60 being the only ones to see an increase. For women up to age 50 there is also some decline over that period, though much less pronounced than for men and varying across age groups. What is striking, though, is that for men the decline since 2000 represents a continuation of a longer-term trend (albeit accelerated during the crisis), whereas for women it is a reversal of the upward trajectory seen up to that point. In the UK, by contrast, the male participation rate also declined up to 2000 for most age groups, but by 2017 it was generally as high as in 2000 or higher (except for youngest age group), and the rate for women aged 25 or over has continued to rise. As a result, participation rates are now higher in the UK than the US for both men and women in each age group up to the age of 60.

3. Existing research

The decline in the US labour force participation rate since the turn of the millennium has fuelled a vigorous debate about the extent to which this primarily reflects cyclical forces or longer-lasting structural factors, and about the nature of those factors. An early paper by Aaronson et al. (2006) concluded that cyclical fluctuations in participation were taking place around a declining trend. In the wake of the financial crisis, Aronson et al. (2012) and Van Zandweghe (2012) concluded that more than half of the decline in aggregate US labour force participation from 2000–2011 was due to cyclical factors. Hotchkiss and Rios-Avila (2013) found that nearly all of the decline from 2007–2012 was cyclical. Bengali et al. (2013) also identified a substantial cyclical component in the decline from 2007, as did a study by the Council of Economic Advisers, 2014a; Council of Economic Advisers, 2014b. Aronson et al. (2014) looked at a variety of different approaches and concluded, in contrast, that much of the decline from 2007 was structural in nature.

The most commonly cited structural factor is the ageing of the population and the ‘baby-boom’ cohort. Abraham and Kearney (2018) detailed decomposition exercise distinguishing finely-grained age groups by gender found that changes in age composition and falling participation within age groups among young and prime-age adults have been equally important. The declining participation rate for younger age groups has been attributed in part to increased college attendance. Another hypothesis proposes that an increase in the value of leisure time owing to improved video gaming technology may have increased the relative attractiveness of non-work for young men (Aguiar et al., 2017). Others suggests that changing social norms have made it more socially acceptable for young men to be out of work and relying on support from their parents (Eberstadt, 2016).

For prime-age and older workers, growth in the availability and/or generosity of social insurance programs — including disability insurance, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and publicly provided or subsidized health insurance — have been advanced as contributing to declining participation. The dramatic growth in the prison population and discriminatory employment practices against those with criminal records may also mean more labour force drop-out after release (Western, 2018). The trend towards lower participation has coincided with the increase in premature mortality among non-Hispanic whites, highlighted by Case and Deaton (2017), Case and Deaton, 2017) as “deaths of despair”. The increase in opioid use in particular has received a great deal of attention; Krueger (2016) found, for example, that labour force participation fell more in areas where relatively more opioid pain medication has been prescribed, though causality likely runs in both directions.1

While much of the attention has focused on men, some of these drivers also apply to women, and other factors that may have contributed to the levelling-off in female labour force participation have also received attention. Blau and Kahn (2013) is among the studies highlighting the absence in the US of family-friendly policies such as paid parental leave. Caring for elderly parents may also be a factor, with the share of prime-age workers who have eldercare responsibilities increasing as the baby boom cohort ages. The importance of gender role attitudes has also been debated, with respect for example to the hypothesis that highly educated women have been increasingly ‘opting out’ (Goldin and Katz, 2008; Herr and Wolfram, 2009) or that there has been a ‘rebound in traditional gender role attitudes’ (Fortin, 2015).

With a great deal of attention paid in recent US research to the displacement of workers by a combination of globalization and technological change, including robotisation, some have argued that disappointing levels of participation reflect a growing mismatch between available workers and vacant jobs. The extent to which this is seen in the data, and if so whether it represents a short-term feature of the recession rather than a longer-term and more structural phenomenon, is contested. A related debate is about the extent to which declining rates of geographic mobility have led to lower rates of employment. Molloy et al. (2011), for example, document that internal migration rates have trended steadily downward over the past 25 years and are now lower than at any previous time in the post-war period.

For the UK, research has focused on the relatively limited job loss and unemployment increase during the Great Recession compared with previous downturns, and on the sharp recovery in the employment rate since 2012. This is generally linked to what happened to pay, with the UK seeing the biggest fall in real wages of any G7 country (Taylor et al., 2014), fairly uniform across sectors, so the focus of research has been as much on why wages have performed so poorly. The UK’s high degree of labour market ‘flexibility’ is often advanced as a key factor, but as Coulter (2016) points out, this does not help to explain why the Great Recession was so different from previous recessions since many of the key reforms aimed at increasing flexibility were enacted in the late 1980s, and during the 1990s recession employment, rather than wages, bore the brunt of the shock. Research suggests that more people are willing to work at a given real wage and/or are less responsive to falls in the real wage (Disney et al., 2013), but it is not clear why this would be the case. An aspect that has received attention is capital ‘shallowing’ as opposed to deepening: the fall in the price of labour relative to the cost of capital may have encouraged firms to substitute labour for equipment. Pessoa and Van Reenen (2014) argue that this accounts for up to half of the fall in labour productivity since the start of the Great Recession, with a correspondingly large impact on employment.

A sharp increase in labour market polarisation was also seen in the UK during the recession, with low-skilled jobs expanding their share and medium-skilled jobs continuing to decline (Plunkett and Pessoa, 2013), and sectoral shifts may also have been important in the evolution of average real wages with some higher paying sectors experiencing falls in employment and a marked shift from public to private sector employment. Inward migration may have been associated with greater willingness to work in insecure sectors and for lower pay, though empirical studies have not found a statistically significant impact from EU migration on native employment outcomes (Devlin, 2014). Changes in social transfers from 2010, reducing their generosity and increasing conditionality in terms of job search, might have reduced the reservation wage for some. Enhanced family policy may also have played a role in boosting female participation.

4. Method and data

We now set out our approach to understanding the evolution of labour force participation over time in the US and the UK, and how this relates to previous US studies. A useful point of departure is the Aaronson et al. (2006) study employing a cohort-based model.2 In this modelling strategy, participation rates are analysed separately by age group and gender. Controls include only aggregate variables, where aggregation is specific to the different gender and age groups. The controls include the share of individuals with high/low education, the share of individuals living in different types of households (eg, with/without a partner, with/without children), the share of individuals with disabilities, measures of earning potentials such as the (age-specific) gender wage gap, measures of (average) household wealth, measures for business cycle effects, and proxies for the relevant social programs, such as the availability of childcare for women in childbearing years, and the fraction of individuals eligible for early retirement in older cohorts. Because each gender-age subgroup provides one unit of observation, the identification of the effects of each determinant can be obtained only by exploiting its variation over time. Time invariant cohort effects are also included. Aggregation over the different gender-age categories is obtained by weighting the participation rates in each subgroup by the population size of that subgroup.

However, the group-level analysis suffers from what is known as the “ecological fallacy” (see Appendix A). Using micro-data helps to avoid this problem, and it also allows to control for more characteristics.3 This is the strategy used, for instance, by Aronson et al. (2012), who estimate the probability of being in the labour force at the individual level, separately by gender and age groups, in order to allow the cohort effects and other controls to flexibly vary across age, gender, and education. They control for age, year of birth, race, education, the business cycle, plus include additional conditioning variables for specific demographic groups, like the real state minimum wage and the ratio of the average youth hourly wage to average adult hourly wage for the younger age groups, indicators for being married with children and married with a young child for the middle age groups, and gender-specific life expectancies for the older age groups.

We follow this approach here and model participation at the individual level, by considering three groups of variables: (i) individual and household characteristics X, (ii) regional labour market characteristics L, and (iii) regional policies P. Participation is therefore modelled as

To obtain a more flexible specification, equation (1) is estimated separately by gender.

One major challenge for this comparative exercise is obtaining consistent and homogeneous data, meaning that variables have the same meaning irrespective of time and space.4 We use the Labour Force Survey (LFS) for the UK and the Current Population Survey (CPS) for the US. For each year, we select the second quarter LFS for the UK and the March CPS for the US, because these particular surveys contain additional information. Our data are repeated cross-sections.

Most of the data constraints are in the UK data, as the Office for National Statistics does not attempt to homogenize variables in the face of significant changes in the questionnaire over the years. We select only variables that can be traced back with a sufficient level of reliability (allowing minor changes in the filtering conditions or categorical values). There is a tradeoff between the number of variables that can be included and the length of the time series. We focus on the period between 1996 and 2017, as information on educational levels, health status, home ownership, and household composition prior to 1996 becomes difficult to compare with more recent waves. As conservative as this choice can appear, it still precludes the use of retrospective information, in particular the labour market status of individuals in previous periods, which is only available from 2011 onwards. However, while participation in the past is possibly the single most important predictor of current participation, its inclusion would in any case have been problematic. This is because, without controlling for individual effects (which is possible only using panel data), the lagged endogenous variable will soak up the effects of unobserved heterogeneity, hence introducing an upward bias in true state persistence. Finally, in the LFS it is not possible to reconstruct the labour market status of partners.

While these data limitations with respect to the UK constrain our choices of covariates for the US, we end up with datasets for the two countries that are highly comparable. The differences are:

Health: We define “bad health” in the UK data as having a health problem that limits the kind of paid work that the respondent can do, while in the US data we define it as being in the lower two categories of five-category self-reported health status. The resulting fraction of individuals with “bad” health is larger in the UK than in the US, as shown in the descriptive statistics (see Table 1).

Race: A dummy for Hispanic is added for the US.

Household type: The US data allow distinguishing married couples living together from married individuals living with a partner outside marriage. We follow the UK definition and distinguish only between married individuals living alone and married individuals living with their partner, irrespective of whether the partner is their spouse or not.

Children: The UK data provide dummies for the presence of children of different ages (under 2, 2–4, 5–9, 10–15) in the household. They do not provide information on the number of children in each age group. The US data records the overall number of children and the age of the youngest and the oldest child. From this we reconstructed dummies for the youngest children being in each relevant age group (under 2, 2–4, 5–9, 10–15). Consequently, it is possible that all flags related to children are switched on in the UK data while in the US data they are mutually exclusive.

Home ownership: In the UK data it is possible to distinguish between whether the house is owned outright or with an ongoing mortgage. Information on mortgages is available only from 2010 onwards in the US data and is therefore not included.

Average values

| US | UK | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 2017 | 1996 | 2017 | ||

| Active | 0.775 | 0.743 | 0.778 | 0.798 | |

| Student | 0.106 | 0.150 | 0.070 | 0.088 | |

| NEET (15-24) (a) | 0.232 | 0.220 | 0.241 | 0.175 | |

| Age | 37.0 | 38.5 | 38.1 | 40.1 | |

| Year of birth | 1959.0 | 1978.5 | 1957.9 | 1976.9 | |

| Race black | 0.099 | 0.123 | 0.015 | 0.030 | |

| Race other | 0.049 | 0.108 | 0.040 | 0.103 | |

| Hispanic | 0.152 | 0.204 | |||

| Foreign born | 0.150 | 0.192 | 0.078 | 0.177 | |

| Foreign national | 0.094 | 0.102 | 0.047 | 0.142 | |

| Education low | 0.202 | 0.156 | 0.359 | 0.164 | |

| Education medium | 0.581 | 0.545 | 0.442 | 0.447 | |

| Education high | 0.218 | 0.299 | 0.199 | 0.388 | |

| Household single alone | 0.272 | 0.312 | 0.260 | 0.283 | |

| Household single cohabiting | 0.020 | 0.043 | 0.054 | 0.121 | |

| Household married alone | 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.003 | |

| Household married cohabiting | 0.565 | 0.510 | 0.557 | 0.487 | |

| Household separated alone | 0.025 | 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.023 | |

| Household separated cohabiting | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.003 | |

| Household divorced alone | 0.082 | 0.070 | 0.052 | 0.048 | |

| Household divorced cohabiting | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.019 | 0.023 | |

| Household widowed alone | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.009 | |

| Household widowed cohabiting | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Number of children | 0.953 | 0.950 | |||

| Household child under 2 (b) | 0.080 | 0.065 | 0.078 | 0.074 | |

| Household child 2–4 (c) | 0.090 | 0.084 | 0.114 | 0.116 | |

| Household child 5–9 (d) | 0.105 | 0.104 | 0.173 | 0.182 | |

| Household child 10–15 (e) | 0.105 | 0.111 | 0.210 | 0.206 | |

| Health bad | 0.092 | 0.097 | 0.152 | 0.139 | |

| Home owned | 0.664 | 0.645 | 0.729 | 0.646 | |

| Home owned outright | 0.154 | 0.199 | |||

| Home owned mortgage | 0.576 | 0.447 | |||

| Rural | 0.220 | 0.172 | |||

| Unemployment rate (regional or state level) | 0.061 | 0.048 | 0.084 | 0.045 | |

| GDP per capita (national currency) | 29,615 | 58,081 | (2016) | 15,526 | 30,850 |

| Minimum wage (% of GDP per capita) (f) | 0.154 | 0.147 | (2016) | 0.000 | 0.233 |

| Social expenditure family (% of GDP) (g) | 0.5 | 0.7 | (2016) | 2.2 | 3.8 |

| Social expenditure total (% of GDP) (h) | 14.8 | 19.3 | (2016) | 18.1 | 21.5 |

| Maternity total protected (weeks) (i) | 12 | 12 | (2016) | 40 | 70 |

| Maternity total paid (weeks) (j) | 0 | 0 | (2016) | 18 | 39 |

| Paternity total specific (weeks) (k) | 12 | 12 | (2016) | 0 | 20 |

| Paternity total specific paid (weeks) (l) | 0 | 0 | (2016) | 0 | 2 |

| AFDC/TANF/SNAP (m) | 29.3 | 21.2 | (2016) | ||

| SSI federal (n) | 16.4 | 13.4 | (2016) | ||

| EITC2max (o) | 124.0 | 102.0 | (2016) | ||

| EITC state (p) | 0.027 | 0.160 | (2016) | ||

-

a

Not in employment, education or training.

-

b

UK: presence of children below 2. US: youngest child below 2.

-

c

UK: presence of children aged between 2 and 4. US: youngest child aged between 2 and 4.

-

d

UK: presence of children aged between 5 and 9. US: youngest child aged between 5 and 9.

-

e

UK: presence of children aged between 10 and 15. US: youngest child aged between 10 and 15.

-

f

UK: national minimum wage. US: state minimum wage. Normalised by GDP per capita (000).

-

g

Social expenditures on family policies (% of GDP).

-

h

Social expenditures, total (% of GDP).

-

i

Maximum weeks of job-protected maternity, parental and home care leave available to mothers, regardless of income support.

-

j

Total weeks of paid maternity, parental and home care payments available to mothers.

-

k

Total weeks of leave reserved for exclusive use by the father.

-

l

Total weeks of paid leave reserved for exclusive use by the father.

-

m

Combined monthly maximum AFDC/TANF and Food Stamps benefits for a 4-person family. Normalised by GDP per capita and multiplied by 1,000.

-

n

EITC maximum credit for two dependents. Normalised by GDP per capita (000).

-

o

Monthly maximum federal SSI benefits for individuals living independently. Normalised by GDP per capita (000).

-

p

State EITC rate as percentage of Federal credit.

Data for social policies come from the OECD Social Policy database. They include the amount of social expenditures for family policies and the amount of total social expenditures, both as a percentage of GDP.

Data for family policies are taken from the OECD Family database. The variables selected are Maternity total protected weeks, defined as the maximum weeks of job-protected maternity, parental and home care leave available to mothers, regardless of income support, maternity total paid weeks, the total weeks of paid maternity, parental and home care payments available to mothers, paternity total specific weeks, the total weeks of leave reserved for exclusive use by the father, and paternity specific paid weeks, the total weeks of paid leave reserved for exclusive use by the father. Data are restricted to 2016 for the US.

In the analysis of the US, we use additional state-level policy information provided by the University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research (UKCPR).5 In particular, we consider the following variables: AFCD/TANF/SNAP, the combined monthly maximum AFDC/TANF and Food Stamps benefits for a 4-person family; EITC2max, the EITC maximum credit for two dependents; EITC state, the state EITC credit as percentage of the federal credit; and SSI federal, the monthly maximum federal SSI benefits for individuals living independently.6]

The minimum wage is at the national level for the UK. For the US, we use the state minimum wage, as provided by the UKCPR.

We normalise monetary variables, including the minimum wage, by the GDP per capita (in thousands of dollars/pounds). As monetary variables (benefits and the minimum wage) have state variation in the US, we use state-level GDP per capita for the US. As the only monetary variable for the UK is the minimum wage, which has only national variation, we use national GDP per capita for the UK. This normalisation eliminates the need to convert currencies and to adjust for inflation. Moreover, GDP and GDP per capita are potentially endogenous to the participation rate, with reverse causality running from participation to income and income per capita. If this is the case, the minimum wage and the social benefits, which are obviously influenced by the level of income (both real and nominal), are also endogenous. Our normalisation should help net this out and leave only a measure of the relative generosity of the policy. To be more concrete, let the policies P be a function of GDP per capita, y:

where GDP per capita is potentially a function of participation:

Normalising the policy indicators by the level of GDP per capita breaks the endogeneity problem if the function g is approximately linear:

However, some policies — in particular the minimum wage — may be affected by the participation rate not only indirectly, via the level of income, but also directly, as in:

This could happen if politicians see the minimum wage as a way to influence participation. Our normalisation is not safe against this possibility. This suggests caution is needed in interpreting the coefficient for the (normalised) minimum wage.

We end up with 1,550,258 observations for the UK and 2,528,122 observations for the US. Minimum legal working age is 16 in the UK and 14 in the US, with limits on the number of hours worked by minors under the age of 16. Hence, we focus on the 16-and-over population. As labour market status is not recorded in the UK data for individuals above state pension age unless they are working, and state pension age has changed over the years, we restrict our analysis to females under 60 and males under 65.

Average values for the variables we include in the analysis, in the initial and final year, are reported in Table 1.

Data sources: UK LFS Q2; March CPS; OECD Family and Social Policy databases; University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research, UKCPR National Welfare Data 1980–2016.

In the analysis, we focus on the non-student population. The trends in labour force participation shown above in Figures 3 and 4 remain substantially unchanged when students are excluded.

With these data, we estimate logistic regression models that include the following variables:

Demography: age (squared polynomial), cohort (squared polynomial),7 race (white, black or other), ethnicity (US only: Hispanic or other), country of birth (foreign or domestic), citizenship (foreign or domestic).

Education: low, middle or high.

Household type: marital status (single, married, separated, divorced or widowed), interacted with cohabitation (presence of a partner).

Children: age of children (US only: number of children).

Health: self-reported bad health status.

Home ownership: rent or ownership (UK only: presence of a mortgage).

Geography: 20 regions for the UK, 56 FIPS codes for the US, plus an urban/rural indicator for the US.

Business cycle: regional unemployment rate, post-crisis (2009 onwards) dummy.

Policies: minimum wage, characteristics of family policies (number of weeks of maximum and parental leave and number of weeks of paid parental leave, for both men and women), amount of social expenditures in % of GDP, additional indicators for the generosity of the AFDC/TANF/Food Stamp/EITC/SSI programs for the US.

Time interactions: year interacted with health status and education. This allows the effects of health and education to vary over time, with a linear trend.

Since there is no longitudinal variation in the family policy measures at the federal level in the US, these are excluded for the US. To measure the business cycle, we prefer the unemployment rate over other measures like the gap between GDP and potential GDP (as employed by Aronson et al., 2012), as the unemployment rate has regional variation.

In the main analysis, age, period, and cohort effects are disentangled by means of parametric assumptions. Specifically, age and cohort are assumed to enter with a quadratic specification, while period effects are proxied by the business cycle.

5. Analyses

The results are reported in Table 2. The model is estimated separately by gender and country (for non-students only). The baseline is a white individual with middle education, single (and not cohabiting), renting (rather than owning), who lives in London (UK) or urban California (US).

Logit estimates of the probability of being in the labour force

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | UK | US | UK | |||||

| Male | Male | Female | Female | |||||

| Variables | 16–64 | 16–64 | 16–59 | 16–59 | ||||

| Age | 0.123 | *** | 0.178 | *** | 0.076 | *** | 0.156 | *** |

| Age squared | −0.002 | *** | −0.003 | *** | −0.001 | *** | −0.002 | *** |

| Year of birth | 0.029 | *** | 0.047 | *** | 0.034 | *** | 0.056 | *** |

| Year of birth squared | 0.000 | *** | 0.000 | *** | 0.000 | *** | 0.000 | *** |

| Race black | −0.479 | *** | −0.315 | *** | 0.174 | *** | 0.231 | *** |

| Race other | −0.367 | *** | −0.447 | *** | −0.109 | *** | −0.712 | *** |

| Foreign born | 0.311 | *** | 0.222 | *** | 0.003 | −0.063 | *** | |

| Foreign national | 0.112 | *** | −0.082 | *** | −0.519 | *** | −0.043 | *** |

| Hispanic | 0.111 | *** | 0.105 | *** | ||||

| Education high | −31.25 | *** | −4.44 | −24.42 | *** | 10.35 | *** | |

| Education low | 3.050 | 5.772 | * | −13.140 | *** | 25.070 | *** | |

| Health bad | −8.532 | ** | −47.640 | *** | 29.210 | *** | 0.993 | |

| Year x health | 0.003 | * | 0.023 | *** | −0.015 | *** | −0.001 | |

| Year x education high | 0.016 | *** | 0.002 | 0.012 | *** | −0.005 | *** | |

| Year x education low | −0.002 | −0.003 | * | 0.006 | *** | −0.013 | *** | |

| Household single cohab | 0.735 | *** | 0.617 | *** | 0.191 | *** | 0.212 | *** |

| Household married alone | 0.639 | *** | 0.804 | *** | −0.050 | * | −0.167 | *** |

| Household married cohab | 0.899 | *** | 0.730 | *** | −0.384 | *** | −0.141 | *** |

| Household separated alone | 0.443 | *** | 0.361 | *** | 0.200 | *** | 0.037 | * |

| Household separated cohab | 0.548 | *** | 1.030 | *** | 0.063 | 0.399 | *** | |

| Household divorced alone | 0.486 | *** | 0.307 | *** | 0.315 | *** | 0.206 | *** |

| Household divorced cohab | 0.793 | *** | 0.689 | *** | 0.197 | *** | 0.300 | *** |

| Household widowed alone | 0.133 | *** | 0.238 | *** | −0.431 | *** | −0.084 | *** |

| Household widowed cohab | 0.351 | *** | 0.544 | *** | −0.248 | *** | 0.059 | |

| Household child under 2 | 0.041 | −0.114 | *** | −0.967 | *** | −1.479 | *** | |

| Household child 2–4 | 0.013 | −0.205 | *** | −0.645 | *** | −1.283 | *** | |

| Household child 5–9 | 0.067 | *** | −0.225 | *** | −0.285 | *** | −0.759 | *** |

| Household child 10–15 | 0.169 | *** | −0.145 | *** | 0.071 | *** | −0.429 | *** |

| Number of children | 0.139 | *** | −0.094 | *** | ||||

| Home owned | 0.068 | *** | 0.182 | *** | ||||

| Unemployment rate | −1.215 | *** | −0.023 | 0.615 | ** | −0.038 | ||

| Post-crisis | 0.116 | *** | 0.089 | ** | 0.083 | *** | 0.043 | |

| Minimum wage | −0.546 | −0.243 | * | 0.910 | *** | −0.010 | ||

| Social expenditure family | −0.104 | ** | −0.031 | 0.091 | ** | 0.005 | ||

| Social expenditure total | −0.008 | −0.010 | −0.021 | ** | −0.008 | |||

| AFDC/TANF/SNAP | −0.014 | *** | −0.018 | *** | ||||

| SSI federal | 0.003 | 0.022 | ||||||

| EITC2max | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

| EITC state | −0.022 | 0.019 | ||||||

| Rural | −0.137 | *** | 0.007 | |||||

| Home owned outright | 0.240 | *** | 0.320 | *** | ||||

| Home owned mortgage | 1.232 | *** | 1.056 | *** | ||||

| Maternity total protected | −0.007 | *** | −0.008 | *** | ||||

| Maternity total paid | 0.006 | *** | 0.000 | |||||

| Paternity total specific | 0.007 | * | 0.007 | *** | ||||

| Constant | 1.127 | *** | −0.792 | 0.461 | ** | −3.431 | *** | |

| Observations | 1,063,351 | 718,417 | 1053301 | 704,235 | ||||

| chi2 | 97,216 | 120,525 | 79,867 | 120,176 | ||||

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| r2_p | 0.239 | 0.364 | 0.118 | 0.246 |

-

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

-

Students excluded. The baseline is a medium education white individual, single and not cohabiting, living in urban California (US) or central London (UK), and renting. Cohort is measured subtracting 1,900 from year of birth. State (US) and NUTS1 (UK) regional dummies included.

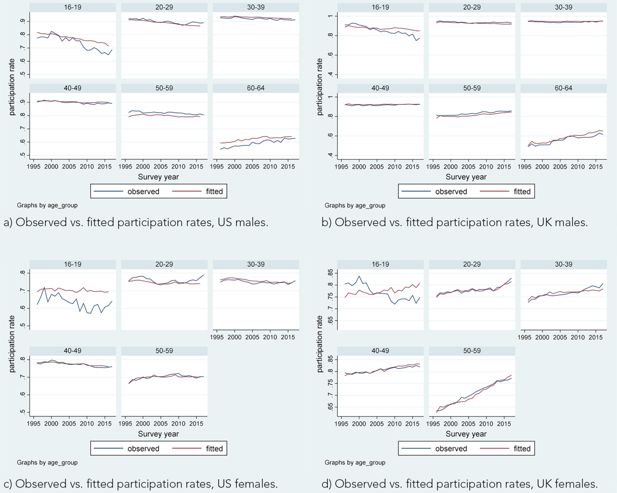

Figure 5a–d show the actual versus estimated participation rates. Apart from the age group 16–19, where the population of non-students is very small, the goodness of fit is high.

Observed vs. fitted participation rates, (a) US males, (b) UK males, (c) US females, (d) UK females. Coefficients as in Table 2.

Most of the estimated effects in Table 2 go in the expected direction. In both countries, being black reduces ceteris paribus participation for males and increases it for females. Male immigrants (born outside the country) are more likely to be in the labour force in both countries, all else equal, whereas for women that effect is insignificant in the US and negative in the UK. Hispanics participate more in the US, whether male or female. Living with a partner outside marriage increases participation for both genders, compared to living alone, while marriage increases participation for males and decreases it for females. Being separated or divorced increases participation for both genders. Widowhood increases participation for males and decreases it for females. Home ownership is associated with increased participation, and in the UK (whether outright owners versus those with mortgages can be distinguished) this is most pronounced in presence of a mortgage; it should be noted, though, that causality could well go in the other direction, from participation to home ownership.8 Having older children in the household increases participation for males in the US but decreases it in the UK; female participation is generally reduced by children in both countries.

Business cycle conditions seem to matter only in the US, decreasing participation for males and increasing it for females. The positive post-Great Recession dummy variable we find in the US case goes against the narrative of a negative structural break taking place around that time in the US; any such effect is more muted in the UK, though still positive for men.

The minimum wage, normalised by GDP per capita, has a positive effect for females in the US; in all other cases it is either not significant or only weakly so. Expenditure on family policies at the national level has a negative impact on participation for males and a positive impact for females, but only in the US. Higher AFDC/TANF benefits and Food Stamps are associated with lower participation for both males and females in the US. Greater maternity leave is associated with slightly lower female participation in the UK, while the opposite is the case for paternity leave. (Such a relationship cannot be probed for the US as there is no variation in the duration of leave periods across the sample).

Overall, the multivariate analysis confirms the divergence in labour force participation patterns between the US and the UK observed in the raw data. And it offers a number of clues about the sources of this divergence. Three are of particular importance.

First, contrary to the popular narrative that sees a specific participation problem for US males, the US-UK divergence is particularly marked for the female population.

Second, education appears to have been an important part of the story. Table 3 brings out that, after taking into account the interaction with time, high education has a positive effect on participation, although for men in the UK the effect is very limited, and low education has a negative effect throughout. The positive effects of high education are increasing over time in the US, both for males and females, while they are much more constant in the UK. The negative effects of low education do not vary much over time in either country, for men. For women, they are decreasing over time in the US, and increasing in the UK.

Effects of education and health over time

| Males | Females | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | UK | US | UK | ||||||

| Case | Reference category | 1996 | 2017 | 1996 | 2017 | 1996 | 2017 | 1996 | 2017 |

| Education High | Education Medium | 0.29 | 0.62 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.47 |

| Education Low | Education Medium | −0.58 | −0.62 | −0.40 | −0.46 | −0.80 | −0.67 | −0.48 | −0.75 |

| Health Bad | Health Good | −2.16 | −2.10 | −2.73 | −2.26 | −1.33 | −1.65 | −1.90 | −1.93 |

-

Notes: The table reports the contribution to the logit score from Table 2. The non-linearity of the logit function means that the same increase in the logit score has a different impact on the estimated probability depending on the starting value of the score.

It is particularly noteworthy that in the US the impact on labour force participation of low education hasn’t changed over time for men, and has become less unfavourable for women. This is contrary to the popular story that changes in the labour market have made it much more difficult or less attractive for Americans with limited education to participate.

Over the period covered by our analysis, 1996–2017, the proportion of the working-aged population with low education fell much more rapidly in the UK than in the US. The decline in the UK was 20 percentage points, versus just four percentage points in the US (Table 1). This difference in compositional shift is likely to have had a large effect on the differing labour force participation trends in the two countries. Similarly, the share with high education increased by 18 percentage points in the UK, compared to eight percentage points in the US (Table 1). Although the effects of high education increased over time in the US but not in the UK, the compositional shift is likely to have overwhelmed this and thus contributed to the better labour force participation trend in the UK.

A third key finding is that health appears to have mattered less than some have hypothesized. In Table 3 we see that bad (self-reported) health has a negative effect on participation. The negative effects of bad health remain more or less constant over time for US males and UK females, whereas they get smaller (less negative) for UK males and larger (more negative) for US females. So in the US case, where the relationship between health and participation for men has been such a focus in recent debate, there is no evidence that those in bad health have become less likely to participate over time; it is only for women that any such pattern is seen. The proportion reporting their health to be ‘bad’ rose only marginally in the US (Table 1). This lack of a significant rise, coupled with the fact that the impact of health didn’t change for individuals, casts doubt on the much-discussed role of increasing levels of ill-health and the opioid crisis in reducing labour force participation in the United States.

How much have cyclical forces mattered? Our strategy for distinguishing the role of cyclical factors relative to structural factors in accounting for the differing over-time patterns in the US and the UK is to examine age, period, and cohort effects. Age and cohort effects, as well as the effects of the other characteristics analysed above, are considered ‘structural’. The so-called ‘period’ effect, which we measure through macroeconomic variables, captures the cyclical component.

Starting from the age and cohort effect, Figures 6 and 7 display the estimated participation probabilities for different ages and cohorts respectively, at the average values of all other covariates.9

Female participation increases much more steeply at younger ages in the UK than in the US, while for both genders participation starts decreasing later in life. Male participation rates for later cohorts, after controlling for other characteristics, are basically flat in the UK, but are trending downwards in in the US. The difference is even more prominent for women, where the cohort effects are positive for the UK, and negative for the US. The ageing of the baby boom generation is thus having a greater impact in the US than the UK for two reasons: the decline in participation rates with age is more marked in the US, and the baby boom generation is a relatively high-participation generation in the US compared with younger generations, a good deal more so than in the UK, so its gradual exit from the working age population is more detrimental to overall labour force participation there. While ageing is more pronounced in the UK than in the US, the negative impact on participation is more pronounced in the US.

As already noted, the truly ‘cyclical’ component is captured, in our model, by macroeconomic variables: the unemployment rate and a post-2008 dummy. In particular, the positive or non-significant coefficient associated to the post-2008 period shows that the cyclical component was not worse during the Great Recession than in other recessions. If anything, the Great Recession had a milder effect (for each percentage point increase in the unemployment rate) than other recessions.

Robustness checks on our specification for the APC analysis are performed in Appendix B.

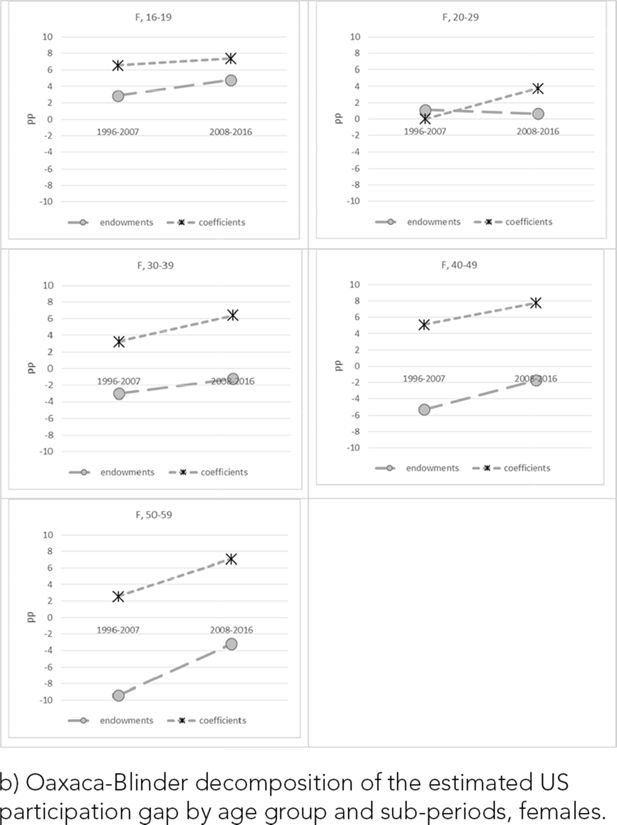

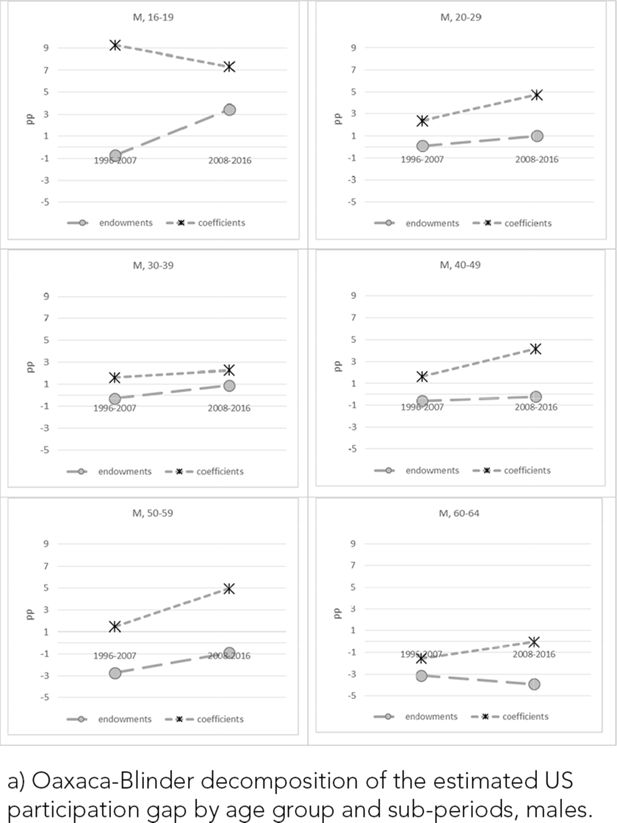

Given the centrality of structural factors, we are particularly interested in understanding the relative importance of differences in the composition of the population (endowments) versus differences in behaviour (as reflected in the estimated coefficients in our models) in explaining the different trajectories of participation in the US and the UK. For example, are these driven by changes in the age or education profile of the working-age population, or by changes in the likelihood that someone of a given age and education will be participating? We explore this by means of an Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition exercise for logit models, the standard approach employed in such contexts. The details of this analysis are in Appendix C. The Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition focuses on whether that part of the structural component attributable to specific covariates reflects composition effects or behavioural effects.

The answer is both, with approximately equal impact. Dividing our sample into two sub-periods, 1996–2007 and 2008–2017, we decomposed the average difference in participation between the two countries into the difference attributable to ‘endowments/characteristics’ of the working-age population versus ‘behaviour’ as reflected in the estimated coefficients on these characteristics in our econometric models. For men, there was a negligible average participation gap between the two countries in the first period, whereas by the second period a substantial gap had emerged. In the first period, the “endowments” of the working-age population were more positive for participation in the US, but this was almost exactly offset by negative behavioural effects. By 2008–2017, the positive effect of endowments for the US in reducing the participation gap had effectively disappeared, while the negative effect of coefficients had also increased substantially. In the earlier period US women had an even greater advantage over their UK counterparts than men in terms of employment-related characteristics; by the latter period this had fallen by three-quarters, and the effect of coefficients/behaviours in widening the participation gap were also greater. For both men and women, the overall deterioration in US participation rates vis-à-vis the UK is quite evenly split between changes in endowments and in coefficients.

Behaviour was less favourable to participation in the US in the first period, but this disadvantage has increased in the second period. For men this is particularly related to the labour force participation of married men, who had been more likely to participate in the US than the UK but this is no longer the case. For women the overall behavioural effect reflects relatively small changes for most of the variables, together with an increased effect of general trends related to age, cohort, and residual effects.

The composition of the population was previously more favourable to participation in the US than in the UK, but that advantage has been lost, primarily due the rapid increase in educational attainment in the UK. The share of men with low education in the US went down only four percentage points, from 21% in 1996 to 17%, while in the UK it went down 14 percentage points, from 32% to 18%. The difference is even more striking for women: in the US, the share of women with low education also went down four percentage points, from 19% in 1996 to 15% in 2017, while in the UK it went down a spectacular 25 percentage points, from 40% to 15%. High education also plays a role. The share of men with high education went up only five percentage points in the US, from 23% in 1996 to 28% in 2017, while in the UK it went up 16 percentage points, from 21% to 37%. For women, the difference is again more pronounced. The share of women with high education in the US went up 11 percentage points, from 21% in 1996 to 32% in 2017, while in the UK it went up 22 percentage points, from 19% to 41%.

6. The US-UK contrast in broader comparative context

The turnaround in US labour force participation, from rapid increase in the 1980s and 1990s to decline in both absolute and relative (to other nations) terms since 2000, is a puzzling development. We have attempted to understand the American experience via an in-depth comparison with the United Kingdom, a country that is similar in labour market regulation and monetary governance and that experienced comparable employment performance up to 2000.

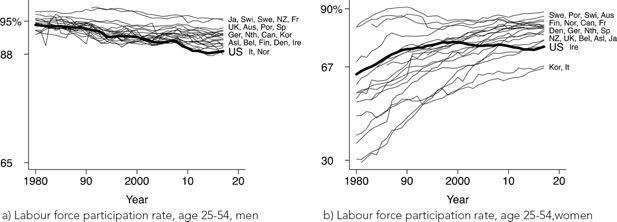

Our analysis suggests three core conclusions. First, the weakening of US labour force participation is not mainly a story of (white) males. The decline in participation has been even more significant among American women, and for women, unlike for men, this decline is a change from the pattern that obtained in the 1980s and 1990s. Figure 9a and b show that this conclusion isn’t peculiar to our US-UK comparison. We also observe it when we consider all of the rich longstanding democratic nations. Figure 8 shows labour force participation rates among prime-working-age (25–54) men, and Figure 8b does so for prime-age women. Among men, the labour force participation rate in the United States has fallen more rapidly than in most other nations, but the US already had one of the lowest rates by 2000. Among women, by contrast, the US in 2000 ranked tenth out of the twenty-one countries in prime-age labour force participation. By 2017, the US ranking had fallen to eighteenth.

(a) Labour force participation rate, age 25–54, men, (b) Labour force participation rate, age 25–54, women The line for the United States is in bold.

Data source: OECD.

Our second key conclusion is that structural forces have played a more important role in the falling US labour force participation rate than cyclical factors. Especially noteworthy is that we find the 2008–09 Great Recession and its aftermath to have been no more influential than prior recessions in driving lower participation rates in the United States. This too is evident in Figure 9a and b. The decline in prime-working-age male labour force participation has been a steady pattern over a number of decades, and the decline in female participation has been a steady pattern since the turn of the century.

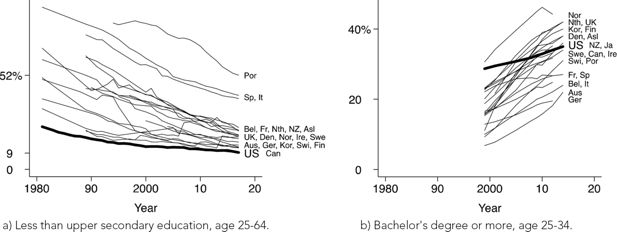

(a) Less than upper secondary education, age 25–64, (b) Bachelor’s degree or more, age 25–34. The line for the United States is in bold.

Data source: OECD.

Our third conclusion is that the influence of structural forces is a product of both changes in composition and changes in behaviours. Among these changes, we found a particularly influential one in the US-UK contrast to be the much slower increase in educational attainment in the United States.

Here too we can spot this in a broader comparison, as we see in Figure 9a and b. Figure 9a shows the share of 25-to-64-year-olds that have completed less than upper secondary education. The share of Americans with low education is among the lowest in this group of nations, but that has been true for decades, and during this period other countries have been catching up, with their low-educated share falling at a faster rate. In other words, not only the UK but virtually every other rich democratic nations has been making more rapid progress than the United States in increasing educational attainment at the low end.

The same is true at the high end, as we see in Figure 9b. This chart shows the share of 25-to-34-year-olds with a bachelor’s degree or more. These data are only available since 2000, but here too we see the United States starting in a leading position but other nations catching up quickly, and here even surpassing the US by the 2010s.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the United States was widely viewed as an affluent democratic country that had comparatively high poverty and inequality but was successful in achieving high employment (OECD, 1994; Scharpf and Schmidt, 2000; Kenworthy, 2008). This success was commonly attributed to its comparatively deregulated labour markets, low wages, and limited taxes and government benefits. America’s disappointing employment performance since the turn of the century suggests this view was either wrong or specific to a particular historical period.

If an embrace of “low-road capitalism” no longer yields good employment outcomes for the United States, what will? Our findings suggest that a focus on males or on cyclical patterns is likely to be of limited help. Longer-term structural developments affecting both men and even more so women are at the core of the problem. It may well be, as an emerging view suggests, that an expansion of family-friendly programs such as early education and paid parental leave would be of considerable help. But our analyses suggest the US might also do well to turn its attention to educational attainment.

Footnotes

1.

Among the few such results available in the research literature, quasi-experimental evidence for Denmark shows that a 10 percentage point higher opioid prescription rate leads to a 1.5 percentage point decrease in labour force participation for an average individual (Laird and Nielsen, 2016).

2.

The same methodology is used, among others, by the European Commission in its 2015 Ageing Report – see European Commission (2014), European Commission, 2015).

3.

One could use micro-data and then aggregate them and run a cohort-based analysis – this is, for instance, what Aaronson et al. (2006) do. However, the advantages of using an aggregate model then become even less evident.

4.

This does not prevent us from including country-specific covariates in some of the models, when appropriate.

5.

See www.ukcpr.org/data.

6.

We include AFDC/TANF/Food Stamp monthly maximum for a 4-person family only as this is highly correlated with the monthly maxima for other types of family. Similarly for the EITC maximum credit.

7.

Cohort is measured in years from 1900, to reduce the collinearity between cohort and cohort squared.

8.

This could also be a concern for other variables, if less clear-cut. For instance, not participating in the labour market could affect self-perceived health status, while participation could sometimes be a positive for the likelihood of marriage.

9.

These age and cohort profiles should not be interpreted as average participation rates; they are highly hypothetical counterfactuals. For instance, they assume that individuals have at the same time high, medium and low education, in proportion to the share of individuals with high, medium and low education observed in the data. All mutually exclusive categorical variables, which in the data are expressed with a 0–1 dummy variable, have intermediate values in this exercise — not only education, but also marital status, health status, etc. Moreover, all characteristics are kept constant across ages and cohorts. This means for example that we assume the same (“mixed”) marital status irrespective of age, or cohort.

10.

Results for models m0, m2 and m3 are available upon request. The results for a model using the m2 specification on common variables only are presented in Appendix D.

11.

The LR test relies on asymptotic theory, which could be unsatisfactory in m3 given the high degrees of freedom. To be consistent with the asymptotic nature of the test we use the standard asymptotic estimator, based on the observed information matrix, for the variance-covariance matrix, rather than the robust or sandwich estimator we use in our baseline analysis.

12.

The model differs from m2 as it includes only common variables.

Appendix A

Avoiding the Ecological Fallacy

Group-level analysis can suffer from the “ecological fallacy” ((Robinson, 1950)), which arises when aggregate data are used to make inferences about individual level parameters. Many investigators have shown that the aggregate and the individual-level coefficients seldom agree in either magnitude or direction.

For instance, it is possible that the individual probability to participate is higher for the majority of individuals in group A, but group B displays a higher aggregate participation rate. Suppose there are 1,000 individuals in each group. 800 individuals in group A have a probability to participate of 50%, while the remaining 200 individuals have a probability to participate of 0. In group B, 800 individuals have a probability of 40%, and 200 individuals have a probability of 100%. Individuals in group A are more likely to participate than individuals in group B; however, the participation rate is higher in group B (52% versus 40%).

Also, a characteristic might negatively affect the participation rate at the individual level but display a positive association at the aggregate level. As an example, individual wealth might have a negative impact on participation, but aggregate wealth could affect participation even after controlling for individual wealth. This could happen for instance if people are trying to “catch up with the Joneses”, reacting to relative wealth. If the distribution of wealth is skewed enough, a positive association between wealth and the participation rate would be detected, at the aggregate level.

Avoiding the ecological fallacy is important if one wants to identify the channels through which the determinants of participation work. This is particularly important when it comes to evaluating or devising policies aimed at fostering participation. In the example of footnote 4, where both individual and relative wealth matter for particiation, a policy aimed at reducing property taxes for low-value houses on the basis of a positive association between wealth and participation detected at the aggregate level, would achieve the opposite effect of lowering participation rates, both because it increases individual wealth and because it reduces wealth differentials.

Appendix B

Alternative specifications for the Age, Period, and Cohort Effects

One of the principal challenges in interpreting what underlies the observed patterns of labour force participation is distinguishing the effects of age, period and cohort. Labour force participation varies with age, generally rising to middle age and then declining; it may differ from one age group or cohort to another, so that for example at a given age more of those born in 1955 than 1935 are in the labour force; and participation may be higher in one time-period than another, for various reasons including the state of the economy and structural factors. This is an analytical problem that arises in a very wide range of contexts, with which social science has struggled. As is well known, age, period and cohort effects are not separately identifiable, given that

In our analysis we have followed a parametric strategy according to which age and cohort enter the specification with a second order polynomial, while period effects are entirely captured by macroeconomic variables (the regional unemployment rate and a shifter for before/after the financial crisis). In this way, we can identify both the linear and the quadratic effect of age and cohort, up to a constant. Moreover, this lean specification allows us to identify the effects of policies on top of the business cycle, though these also include additional unknown period effects which are not captured by our macroeconomic variables.

To assess this specification choice, we can compare it with a fully saturated model, where dummies are introduced for each region-period interaction. This allows the period effects to differ across regions in a flexible way, but it comes at two costs: (i) the first order (linear) effects of cohort and age are no longer identifiable, and (ii) the effects of policies are also no longer identifiable. Moreover, the degrees of freedom of the model increase enormously (with 50 states in the US and 22 periods, we introduce 1,100 extra variables). Ultimately, the choice is between measuring imprecisely the effects of policies in our baseline model, by being unable to disentangle the residual period effects, and measuring imprecisely the period effects in the saturated model, by being unable to disentangle the effects of policies. An intermediate option is to assume that period effects are homogenous across regions, and introduce (non-interacted) time dummies in the model. This allows one to identify the effects of policy differentials when policies have regional variation (ie, in the US only) with respect to some benchmark - either the national average, or some specific region. However, the linear age and cohort effects are still not identifiable, and only the curvature of the age and cohort profiles, which is an object of lesser interest, can be analysed.

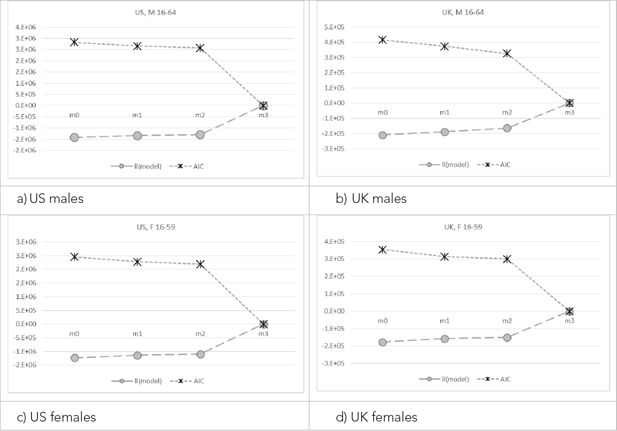

We label our baseline model ‘m1’. The intermediate option is ‘m2’, while the fully saturated model is ‘m3’.

As (i) we are mostly interested in the first order effects of age and cohort, (ii) we have a large number of controls at the individual and regional level that could in principle explain part of the period effects, and (iii) we want to be able to say something about the effects of policies, we tend to prefer our lean specification. However, to assess how much explanatory power we lose by adopting it, we also run the other models, plus a benchmark model labelled ‘m0’ where we do not control for any period effect –that is we exclude all the covariates with only national or regional time variation (the macroeconomic and policy variables). Table B1 summarises the alternative models tested. It highlights the benefits of our lean specification m1; as already noted, this is the only model amongst those considered where the linear age and cohort effects and the policy effects are separately identifiable.

Alternative specifications

| Model name | Treatment of period effect | Linear age and cohort effects identifiable | Policy effects identifiable |

|---|---|---|---|

| m0 | No period effects | Yes | No |

| m1 | Period effects captured by macroeconomic variables | Yes | Yes |

| m2 | Time dummies | No | only policy differentials in the US |

| m3 | Time*region dummies | No | No |

The four models are nested. To further ensure that the estimation sample is the same, we restrict it to 1996–2016 for the US, as policy variables for 2017 were not available for this country at the time of the analysis.10 Standard likelihood ratio (LR) tests on the four models above always reject the simpler models vis-a-vis more flexible ones.11 The ranking does not change when we look at penalised measures of likelihood (AIC and BIC), to take into account the large difference in degrees of freedom. However, as Appendix 1—Figure B1 shows, most of the increase in explanatory power comes from moving from m2 to m3, the saturated model, ie, by allowing for regional differences in period effects. Differences between m1, our baseline model, and m2, the hybrid model, are more modest. While Table B1 highlights the benefits, Appendix 1—Figure B1 depicts the costs associated with our lean specification. On the benefits side, we are able to identify age, cohort and policy effects. On the minus side, we lose only little explanatory power with respect to the hybrid model. Taken together, this reinforces our confidence in the trade-off we have made and the strategy we have employed up to this point in estimating and presenting a model that captures key influences on participation.

Goodness of fit, alternative models. Note: Each panel reports the log likelihood (ll) of the models and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), normalised by the values achieved by the best fit (m3). Higher is better for ll, while lower is better for AIC. Models as in table B1. (a) US males, (b) UK males, (c) US females, (d) UK females.

Appendix C

Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition

We follow Jann (2008) and decompose the difference in the linear prediction in participation rates — that is, in log odds — as:

The first term, , accounts for the difference in endowments; the second term, , accounts for the difference in coefficients, while the third term accounts for an interaction effect. The decomposition is viewed from the point of view of the US.

In order to perform this exercise, we need to adopt a common specification for the two countries, and use common definitions as much as possible. We therefore drop from our model all regional dummies, the rural indicator and the number of children for the US, and create dummies for home ownership and age of youngest child for the UK. We also exclude our health indicator at this point, as we cannot say whether the difference in the proportion of people with bad health in the two countries (see Table 1) is due to a true difference in characteristics, or reflects the difference in the way the indicator is framed. Finally, we are forced to drop all state-level policy variables for the US, and family policy variables at the national level, which have variation only for the UK. This leaves us with a very crude representation of the policy environment — with only minimum wage and social and family expenditure information, both at the national level. This is unsatisfactory, especially in the US where state-level policies have a great deal of variation, and changes the terms of the trade-off in model specification as discussed in Section 5. Hence, we opt for estimation of a model in the spirit of m2 (see Appendix B), with time dummies and macroeconomic (unemployment rate) differentials.12 Finally, we restrict our sample to 1996–2016, as social expenditure variables for 2017 are not available (at the moment of writing) for the US. To see whether the importance of covariates and coefficients has changed over time, we estimate the model separately for the two sub-periods 1996–2007 and 2008–2017. (The estimation results for this common specification are reported in Appendix D.)

Table C1a presents the results of the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition for men, showing for each sub-period the contribution of endowments, coefficients, and interaction between them to the estimated difference in participation rates between the UK and the US. Between 1996 and 2007, there was almost no average participation gap between the two countries, with the participation rate being a mere 0.14 percentage points higher. We see that composition effects work to lower the participation gap from a US perspective — in other words, “endowments” of the working-age population are more positive for participation there, so that predicted participation on that basis would be higher. This is almost exactly offset by negative behavioural effects (“coefficients”), however, which serve to widen the participation gap from a US perspective. These two offsetting effects underpin the almost identical levels of participation observed.

For the 2008–2017 period, by contrast, the average participation gap had become substantial, with participation more than three percentage points higher in the UK. This reflects the fact that the positive effect of endowments for the US (in reducing this gap) fell markedly over time to effectively disappear, while the negative effect of coefficients (in widening the gap) also increased substantially over time (from 1.8 to 3.9 percentage points). Assuming interaction effects are equally attributable to both endowments and coefficients, endowments account for 46% of the overall deterioration in male participation rates, while coefficients account for the remaining 54%.

When looking at the importance of each covariate in the bottom part of the table, we must bear in mind that the effects of age, cohort, and period, given the inclusion of time dummies, are identified only up to a constant (which can be arbitrarily added to either age, cohort, or any combination of the two, or attributed to the dummy for the reference year). We therefore group together the three effects, which also include the effects of policies, under the heading ‘APC’. The main explanation for why composition effects were favourable to the US in the first sub-period, but became negligible in the second sub-period, relates to the education profile of the working-age population. The US started with a lower share of individuals with low education but the UK reduce this share faster, so that the two shares converged over time (as documented in Table D2 below). As far as the effects of behavioural are concerned, the fact that these turned increasingly against the US reflects a turnaround with respect to the likelihood of participation for married men, which reduced the gap in the earlier period but widened it in the later one, together with a reduction in the containment effect of age, period (including policies), and cohort, and a variety of small changes in the contribution of other coefficients. Changes in the effect of high education on participation, on the other hand, served to reduce that gap. The lower impact of home ownership on the propensity to participate in the US had a large effect on the participation gap throughout, but did not change substantially between the two periods.

The corresponding results for females are shown in Table C1b. In the 1996–2007 period the average participation gap was again small, at only 0.17 percentage points. By 2008–2017, the average gap had become even larger than for males, at 4.5 percentage points. The effect of endowments on the gap declined substantially between the two time-periods, reducing the gap from a US perspective by four percentage points in the earlier period but only one percentage point by 2008–2017. In the earlier period US women had an even greater advantage over their UK counterparts than men in terms of employment-related characteristics; by the latter period this had fallen by three-quarters though not disappeared. As for men, the causes of the overall deterioration in female participation rates are roughly equally split between endowments (again, 46%) and coefficients (54%). Similar to men, the main contributory factor is the spectacular reduction in the fraction of working-age individuals with low education in the UK, shown in Table C2. However, the increase in the fraction of high-educated individuals in the UK, which is stronger for females than for males as that table illustrates, also played a role. The effect of coefficients in widening the participation gap for women also increased markedly over time, doubling from 3.3 to 6.61 percentage points; this is mainly due to a change in the overall effect of age, period (including policies) and cohort, which reduced the participation gap in the first period, and increased it in the second period.

Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition of the estimated US participation gap, males

| Males, 16–64 | 1996–2007 | 2008–2017 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK mean | 87.2% | 87.8% | ||

| US mean | 87.1% | 84.7% | ||

| difference UK-US (pp) | 0.14 | 3.12 | ||

| of which: | ||||

| endowments (pp) | −1.75 | −0.04 | ||

| coefficients (pp) | 1.83 | 3.86 | ||

| interaction (pp) | 0.06 | −0.70 | ||

| endowments | coefficients | Endowments | Coefficients | |

| Overall (pp) | −1.75 | 1.83 | −0.04 | 3.86 |

| Contribution of each covariate (pp): | ||||

| APC | −0.77 | −1.04 | −0.01 | −0.25 |

| Race black | 0.78 | 0.46 | −0.05 | 0.44 |

| Race other | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.00 | −0.08 |

| Foreign born | −0.34 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.19 |

| Foreign national | −0.08 | −0.23 | −0.01 | −0.26 |

| Education high | −0.12 | −0.63 | −0.04 | −1.34 |

| Education low | −1.50 | 0.27 | 0.07 | 0.16 |

| Household single cohab | 0.61 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.07 |

| Household married alone | −0.14 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Household married cohab | −0.29 | −1.08 | 0.03 | 0.69 |

| Household separated alone | −0.00 | −0.02 | −0.00 | 0.09 |

| Household separated cohab | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.03 |

| Household divorced alone | −0.27 | −0.13 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Household divorced cohab | 0.11 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.08 |

| Household widowed alone | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Household widowed cohab | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| Household child under 2 | −0.00 | −0.27 | −0.01 | −0.25 |

| Household child 2–4 | −0.01 | −0.36 | −0.00 | −0.28 |

| Household child 5–9 | −0.00 | −0.35 | −0.00 | −0.38 |

| Household child 10–15 | 0.07 | −0.28 | −0.00 | −0.29 |

| Home owned | 0.16 | 5.41 | −0.00 | 5.07 |

| Unemployment rate difference | −0.02 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 |

-

Note: Cells with a positive (negative) contribution to the US participation gap of more (less) than one pp are highlighted in red (green).

Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition of the estimated US participation gap, females

| Females, 16–60 | 1996–2007 | 2008–2017 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK mean | 75.1% | 78.6% | ||

| US mean | 74.9% | 74.0% | ||

| difference UK-US (pp) | 0.17 | 4.54 | ||

| of which: | ||||

| endowments (pp) | −4.05 | −1.17 | ||

| coefficients (pp) | 3.26 | 6.61 | ||

| interaction (pp) | 0.95 | −0.91 | ||

| endowments | coefficients | endowments | Coefficients | |

| Overall (pp) | −4.05 | 3.26 | −1.17 | 6.61 |

| Contribution of each covariate (pp): | ||||

| APC | −0.14 | −2.55 | 0.54 | 1.14 |

| Race black | −0.15 | 0.35 | −0.11 | 0.34 |

| Race other | 0.01 | −0.36 | −0.02 | −0.69 |

| Foreign born | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.08 |

| Foreign national | 0.13 | 0.36 | −0.50 | 0.64 |

| Education high | −0.23 | 0.31 | 1.09 | −0.32 |

| Education low | −4.32 | 0.27 | −2.47 | −0.03 |

| Household single cohab | 0.30 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 0.10 |

| Household married alone | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Household married cohab | 0.29 | 2.54 | 0.67 | 2.39 |

| Household separated alone | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Household separated cohab | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.02 |

| Household divorced alone | −0.25 | −0.11 | −0.15 | 0.12 |

| Household divorced cohab | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Household widowed alone | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| Household widowed cohab | −0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Household child under 2 | −0.02 | −0.95 | −0.51 | −0.87 |

| Household child 2–4 | 0.01 | −1.04 | −0.28 | −1.08 |

| Household child 5–9 | 0.02 | −0.76 | −0.03 | −0.69 |

| Household child 10–15 | −0.00 | −0.51 | −0.00 | −0.48 |

| Home owned | 0.23 | 5.51 | −0.06 | 5.68 |

| Unemployment rate difference | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.00 |

-

Note: Cells with a positive (negative) contribution to the US participation gap of more (less) than one pp are highlighted in red (green).

Trends in educational attainment by gender (sample frequencies)

| Male | Female | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | UK | US | UK | |||||

| 1996 | 2017 | 1996 | 2017 | 1996 | 2017 | 1996 | 2017 | |

| Education Low | 0.210 | 0.167 | 0.320 | 0.182 | 0.194 | 0.145 | 0.399 | 0.146 |

| Education High | 0.229 | 0.279 | 0.210 | 0.366 | 0.206 | 0.319 | 0.189 | 0.411 |

Does the story change if we examine age groups separately? Tables C3a and C3b report the overall estimated US participation gap, and its composition in terms of the effect of endowments, coefficients and interaction, for males and females respectively. The estimated US participation gap has increased in every age group; it is well above 10 pp for the younger age group, and it has turned positive even for those age groups where participation rates in the US where initially higher than in the UK (males 50–59, females 30–39 and females 50–59). The only exception is for males 60–64, where the US still outperform the UK, albeit by a diminished margin.

Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition of the estimated US participation gap by age group and sub-periods, males

| Gender | Male | Male | Male | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age group | 16–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | |||

| Period | 1996–2007 | 2008–2016 | 1996–2007 | 2008–2016 | 1996–2007 | 2008–2016 |

| overall (pp) | 10.6 | 12.9 | 3.0 | 4.7 | 1.3 | 2.7 |

| endowments | −0.7 | 3.5 | 0.1 | 1.0 | −0.3 | 0.9 |

| Coefficients | 9.3 | 7.3 | 2.4 | 4.7 | 1.6 | 2.3 |

| Interaction | 2.1 | 2.1 | 0.5 | −1.1 | 0.0 | −0.5 |

| age group | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–64 | |||

| Period | 1996–2007 | 2008–2016 | 1996–2007 | 2008–2016 | 1996–2007 | 2008–2016 |

| overall (pp) | 1.0 | 3.2 | –0.7 | 3.5 | –4.1 | –2.1 |

| endowments | −0.6 | −0.2 | −2.7 | −0.9 | −3.1 | −3.9 |

| Coefficients | 1.6 | 4.2 | 1.5 | 4.9 | −1.6 | 0.0 |

| Interaction | 0.0 | −0.8 | 0.6 | −0.5 | 0.6 | 1.9 |

Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition of the estimated US participation gap by age group and sub-periods, females

| Gender | Female | Female | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age group | 16–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | |||

| Period | 1996–2007 | 2008–2016 | 1996–2007 | 2008–2016 | 1996–2007 | 2008–2016 |