The Baby Boomers Revisited

- Article

- Figures and data

- Jump to

1. Introduction

Population ageing is a major issue in Australia. The sharp fall in fertility allied with lengthening life spans will result in sharp increases in the number of older Australians in coming years. Population ageing is expected to have profound consequences for government, due to the higher health, aged care and pension costs and slower economic growth associated with an ageing population (Treasury, 2002; Productivity Commission, 2005). During the past few years the Federal Government has been encouraging the baby boomers to save harder and work longer, so that they can help finance a comfortable living standard in retirement. But have these messages been heeded?

In previous issues of the AMP.NATSEM Income and Wealth Report, we have looked at those approaching retirement — but changing labour force behaviour, changes to government benefits and dramatic changes to superannuation all make it timely to reconsider this pre- and early-retirement group. The release in 2006 of new ABS data on the circumstances, spending and savings behaviour of Australians also provides new insights into this crucial cohort (ABS, 2006a).

2. Baby boomers and the labour force

While the age ranges for different generations are somewhat arbitrary, according to demographer Bernard Salt the baby boomers are currently aged around 46-61 years, Generation X are around 31-45 years and Generation Y are around 16-30 years old (Salt, 2001). In the 2004 data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, upon which this reports relies heavily, the boomers are aged about 45 to 59 years — while today, and in some of the later ABS data that we use, some of them have edged into their sixties. In the remainder of this report we are particularly interested in the outcomes just before retirement, so we have also examined outcomes for 60 to 64 year olds (which also accords up with the five year age categories used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics). We have also broken down the information into age groups of 45-54, 55-59, and 60-64 as the behaviour of differing age groups can vary greatly.

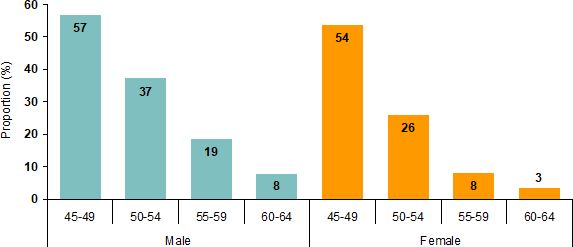

There are currently 5.25 million Australians aged 45-64 or one-quarter of the Australian population. Four out of five of the men in this age group are living as a member of a couple (80%), while three-quarters of the women are a member of a couple (76%) (Table 1). These values are reasonably consistent across the different baby boomer age groups. However, while most of the baby boomers are married, most have recently seen the children leave home or are about experience this ‘joyous’ empty-nest occasion.1 As shown in Figure 1, for males aged less than 50, more than half (57%) are living with children but this proportion drops quickly during their 50s with only one-in-twelve (8%) are living with a child in their early 60s.

Proportions of baby boomers living with dependent children, by gender, 2004. Note: ‘Baby boomers’ is defined colloquially here as persons aged 45 to 64 years.Data source: ABS 2003-04 Survey of Income and Housing unit record data.

Distribution of people aged 45-64 by family type, 2004

| Member of a couple with dependent children | Member of a couple only | A sole parent with dependent children | A single person | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | |

| Male | ||||

| 45-49 | 55.1 | 23.8 | 1.7 | 19.5 |

| 50-54 | 35.4 | 43.4 | 1.8 | 19.4 |

| 55-59 | 17.7 | 63.9 | 0.8 | 17.6 |

| 60-64 | 7.6 | 73.3 | 0.2 | 19.0 |

| Overall | 31.5 | 48.4 | 1.2 | 18.9 |

| Female | ||||

| 45-54 | 44.6 | 31.9 | 9.2 | 14.2 |

| 50-54 | 22.3 | 54.1 | 3.7 | 19.9 |

| 55-59 | 6.9 | 69.6 | 1.1 | 22.4 |

| 60-64 | 2.2 | 70.6 | 1.2 | 26.1 |

| Overall | 21.5 | 54.3 | 4.3 | 20.0 |

-

Source: ABS 2003-04 Survey of Income and Housing unit record data.

Women in these age groups are even less likely to have dependent children than their male counterparts. However, as Table 1 shows, the proportion living as a sole parent is much higher than for males.

3. Baby boomers and the labour force

A critical issue is the proportion of baby boomers that have a job or would like one. International research has suggested that the size of the future fiscal burden that population ageing will create for governments will be greatly reduced if people delay their retirement by even a few years (Cotis, 2003; Fredriksen et al., 2007). As a result, government is keenly watching the labour force participation rates of the baby boomers.

3.1 More boomers in jobs

This has been a good news story over the past five years, with strong economic growth helping more baby boomers to find and keep jobs. By November 2006, about six in every 10 married males aged 60 to 64 year jobs were in the labour force, up from five in every 10 only five years earlier (Table 2). Similarly, for married females, about three in every 10 were in the labour force by 2006, up from about two in every 10 back in 2001. Strong growth is also apparent in the labour force participation rates of unmarried 60 to 64 year olds and in the participation rates of 55 to 59 year olds boomers over the past five years. These are striking changes in employment which will help the boomers to fund their forthcoming retirement.

Labour force participation rates by gender, age and marital status, 1986-2006

| Gender and Age | Marital Status | Participation Rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nov 1996 | Nov 2001 | Nov 2006 | 10-yr change | 5-yr change | ||

| % | % | % | % points | % points | ||

| Male | ||||||

| 45-54 | Married | 90.9 | 90.7 | 91.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Not married | 75.9 | 75.3 | 76.1 | 0.2 | 0.8 | |

| 55-59 | Married | 76.9 | 75.6 | 79.6 | 2.7 | 4.0 |

| Not married | 66.2 | 58.8 | 62.2 | -4.0 | 3.5 | |

| 60-64 | Married | 46.6 | 48.9 | 58.5 | 11.9 | 9.6 |

| Not married | 33.9 | 37.7 | 42.6 | 8.7 | 4.9 | |

| 65+ | Married | 10.3 | 11.7 | 14.8 | 4.5 | 3.1 |

| Not married | 6.7 | 6.5 | 7.6 | 0.9 | 1.1 | |

| All ages (15+) | Married | 75.2 | 74.5 | 74.9 | -0.3 | 0.4 |

| Not married | 69.5 | 67.1 | 66.5 | -3.0 | -0.6 | |

| Female | ||||||

| 45-54 | Married | 68.4 | 71.9 | 77.4 | 8.9 | 5.4 |

| Not married | 69.7 | 68.6 | 73.5 | 3.8 | 4.9 | |

| 55-59 | Married | 40.9 | 49.2 | 58.7 | 17.8 | 9.5 |

| Not married | 46.0 | 49.8 | 61.7 | 15.7 | 11.8 | |

| 60-64 | Married | 18.2 | 22.6 | 31.8 | 13.6 | 9.2 |

| Not married | 16.2 | 27.6 | 36.6 | 20.4 | 8.9 | |

| 65+ | Married | 3.7 | 4.9 | 6.9 | 3.2 | 2.0 |

| Not married | 2.5 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 0.3 | 0.8 | |

| All ages (15+) | Married | 54.9 | 57.6 | 60.2 | 5.2 | 2.6 |

| Not married | 51.9 | 51.3 | 53.4 | 1.5 | 2.2 | |

-

Source: ABS, 2006b.

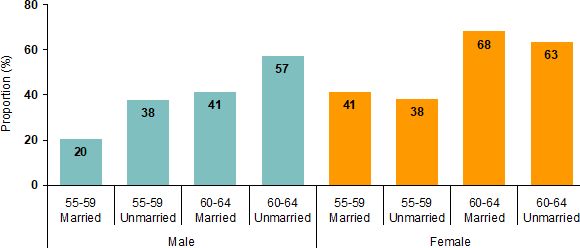

Yet, despite these positive trends, it is still apparent that many baby boomers are retiring early. For example, by age 55 to 59 years, one in every five married and two in every five unmarried baby boomer males have already quit the labour force (Figure 2). By age 60 to 64, the proportions are up to two in every five married and three in every five unmarried males. For baby boomer women, two in every five are out of the labour force by age 55 to 59 and about two in every three by age 60 to 64. So, in summary, by age 60 to 64, the majority of both married and unmarried women and of unmarried men have retired.

Proportions of baby boomers who have retired, by age, gender and marital status, 2004. Note: ‘Baby boomers’ is colloquially defined here as persons aged 45 to 64 years. ‘Retired’ is defined here as those who are not in the labour force.Data source: ABS 2003-04 Survey of Income and Housing unit record data.

Returning to those still in the labour force, Table 2 shows that the highest participation rate is for married men aged 45-54 (92%), with little change for these men over the last decade (up 1.1 percentage points).2 Strikingly, however, married men of this age are much more likely to be participating in the labour force than unmarried men. The participation rate of married men aged 45-54 is around 15 percentage points higher than the rate of unmarried men in this age group. A similar pattern is apparent for all men aged 45-64.

The participation rates for women are lower than for men, as expected. However, the sharp growth in the proportion of women in their late 40s, 50s and early 60s holding down jobs has been one of the factors helping our economy during the past 10 years. The participation rate for both married and unmarried women has gown by around 10 to 20 percentage points over the past decade. While some growth might have been expected in the 60-64 age group due to changes in the eligibility for the Age Pension, the increases in the likelihood of 55 to 59 year old women participating in the labour force have been equally remarkable (up around 18 percentage points for married women and 16 percentage points for unmarried 55 to 59 year old women).3

These changes have been so profound that today some types of baby boomer women are as likely as their male counterparts to hold or want jobs. For example, today 73.5 per cent of unmarried baby boomer women aged 45 to 54 years old are in the labour force, very close to the 76.1 per cent rate notched up by unmarried baby boomer men of the same age. Similarly, 61.7 per cent of 55 to 59 year old women are in the labour force — and this rate may well outpace that for unmarried males of the same age in the near future (currently standing at 62.2 per cent).

The higher participation rates of married men apparent in the Table 2 male data are not evident in the female data. In fact the reverse is true if anything - married women of all ages are slightly less likely to be in the labour force. This presumably reflects the traditional child raising roles of married women.

3.2 The Part-Time Divide

Employed baby boomer women are about thee to four times as likely as employed baby boomer men to work part-time, as shown in Table 3. These differences do not seem to have narrowed very much during the past 10 years, although a shift is evident away from part-time and towards full-time work for baby boomer women in the past five years (shown in the final right-hand column of Table 3).

Proportion of those employed that are working part-time by gender, age and marital status, 1986-2006

| Gender and Age | Marital Status | Proportion working part-time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nov 1996 | Nov 2001 | Nov 2006 | 10-yr change | 5-yr change | ||

| % | % | % | % points | % points | ||

| Male | ||||||

| 45-54 | Married | 4.7 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 2.7 | 0.8 |

| Not married | 10.6 | 10.1 | 14.0 | 3.4 | 3.9 | |

| 55-59 | Married | 10.3 | 12.8 | 12.2 | 1.9 | -0.6 |

| Not married | 14.7 | 15.6 | 17.0 | 2.4 | 1.4 | |

| 60-64 | Married | 18.8 | 22.2 | 24.5 | 5.7 | 2.4 |

| Not married | 17.1 | 22.8 | 26.0 | 9.0 | 3.2 | |

| 65+ | Married | 45.8 | 41.4 | 41.8 | -4.0 | 0.4 |

| Not married | 36.9 | 48.2 | 42.6 | 5.7 | -5.6 | |

| All ages (15+) | Married | 6.7 | 8.6 | 9.7 | 3.0 | 1.1 |

| Not married | 20.5 | 24.4 | 25.1 | 4.6 | 0.7 | |

| Female | 0.0 | |||||

| 45-54 | Married | 45.6 | 46.2 | 42.3 | -3.3 | -3.9 |

| Not married | 28.5 | 32.8 | 30.5 | 2.1 | -2.3 | |

| 55-59 | Married | 53.8 | 53.4 | 49.7 | -4.1 | -3.7 |

| Not married | 40.3 | 34.0 | 30.6 | -9.6 | -3.3 | |

| 60-64 | Married | 65.4 | 62.3 | 58.0 | -7.4 | -4.3 |

| Not married | 36.6 | 53.6 | 38.8 | 2.2 | -14.8 | |

| 65+ | Married | 71.8 | 73.1 | 69.0 | -2.8 | -4.1 |

| Not married | 71.7 | 65.6 | 57.1 | -14.6 | -8.5 | |

| All ages (15+) | Married | 46.3 | 46.7 | 45.9 | -0.4 | -0.8 |

| Not married | 38.2 | 42.9 | 42.2 | 4.0 | -0.7 | |

-

Source: ABS, 2006b.

Another of the interesting trends revealed in Table 3 is the growing preference for part-time work as one ages. About one in every five 60 to 64 year old males who has a job works part-time. This is four times higher, for example, than the proportion recorded by employed married male boomers aged 45 to 54 years (of 4.7 per cent).

The impact of marital status is also again starkly apparent. The proportion of unmarried men aged 45 to 54 working part-time is around double the rate for married men. However for baby boomer women the pattern is again reversed, with married female baby boomers being more likely to work part-time than unmarried female boomers.

4. Baby boomers and their homes

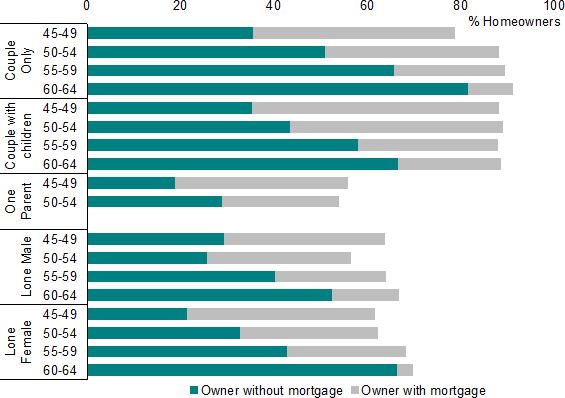

Home ownership has traditionally been the clear favourite preferred tenure in Australian society. With four in every five households headed by a baby boomer owning their own home (with or without a mortgage) it is clear that this preference continues with the baby boomers. It is the major or only savings vehicle for many baby boomer households.

The proportions that are buying or own their own home varies with type of household and age. Figure 3 shows that couples are the most likely to have leapt the home purchase hurdle. Around 90 per cent of couples are living in their own home by age 65. Two-thirds of couples with children and four out of five couples without children own their home outright before age 65.

Proportions of baby boomer home-owning households, by age and household type, 2004. Notes: Mixed households (for example two-family or group households) are excluded from the data above. The sample sizes were too small to provide reliable estimates for one parent households with the reference person aged 55+ and this group has been excluded from the table above. ‘Baby boomer’ households is colloquially defined here as those with a reference person aged 45 to 64 years.Data source: ABS 2003-04 Survey of Income and Housing unit record data (reproduced in Table A1).

In contrast, single baby boomers and those who are sole parents are less likely to have been able to buy the roof over their heads and are thus much more likely to rent (see Table A1 in the appendix). For example, only about 62 per cent of single female baby boomers and 64 per cent of single male baby boomers have managed to purchase their own home by ages 45 to 49, compared with 88 per cent of baby boomer parents with children still at home at the same age. For single baby boomers and couples without children it is clear that, with advancing age, the proportion who manage to buy their own home gradually increases (Figure 3). For example, while 62 per cent of single female baby boomers aged 45 to 49 own their own home, this has crept up to 70 per cent by ages 60 to 64.

And Figure 3 also provides further evidence of the importance that Australians place on paying off the mortgage, with substantial increases with rising age in the proportion who own their home outright. Interestingly, 95 per cent of single baby boomer women aged 60 to 64 years old who are owner occupiers are outright owners — higher than the proportion in any of the other household categories. This compares with only 75 per cent of all couple with children home owners aged 60 to 64 years who are outright owners — presumably reflecting the greater financial burdens faced by those who still have dependent children at home when they are in their 60s.

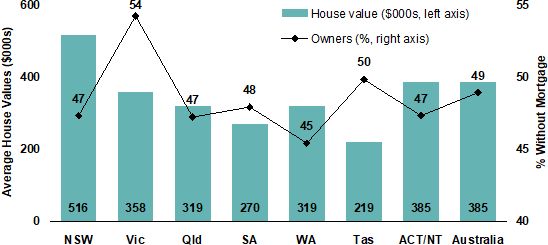

The proportions with and without mortgages do not seem to be strongly correlated with the value of the homes. As Figure 4 shows, the most expensive houses are in New South Wales, but the level of outright ownership there is 47 per cent, a similar value to many other states and territories where average house prices are much lower. The data from Victoria stands out from the others as the prices are reasonably high, but outright ownership levels (54%) by baby boomers are somewhat above all other states.

Proportions of baby boomer households that own their home without a mortgage and house values by state/territory, 2004. Notes: Mixed households (for example two-family or group) are excluded. ‘Baby boomer households’ is colloquially defined here as those with a head aged 45 to 64 years. Average house values are for all baby boomer home owners, not just those who own their home outright.Data source: ABS 2003-04 Survey of Income and Housing unit record data.

5. Baby boomers and debt

Baby boomers are renowned for their comfort with debt. The total debt of baby boomer households is estimated at a hefty $150 billion.

As Table 4 shows, the majority of baby boomer households carry some form of debt. By age 55 to 59 —when, as shown above, up to two in five baby boomers have already retired — a substantial minority are still wrestling with their home mortgage debt. At age 55 to 59, about one-quarter of single baby boomers and of those living with just their partner still have a mortgage to pay. For baby boomers in this age range who still have dependent children at home, the proportion is somewhat higher at 30.1 per cent (Table 4).

Proportions of baby boomer households having debt by age and household type, 2004

| Age Group | Household Type | Any debt | Credit card debt | Rental property loans | Investment loans | Home mortgage | HECS debt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | % | ||

| 45-49 | Couple only | 83.9 | 66.6 | 13.7 | 3.7 | 43.3 | 1.9 |

| Couple with children | 89.0 | 76.8 | 14.5 | 5.5 | 53.2 | 16.7 | |

| One Parent with children | 70.7 | 50.7 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 38.1 | 12.4 | |

| Lone Male | 64.0 | 49.8 | 5.7 | 1.8 | 34.5 | 1.1 | |

| Lone Female | 64.2 | 55.7 | 6.5 | 0.8 | 40.4 | 7.6 | |

| All 45-49 | 81.6 | 68.1 | 11.5 | 4.0 | 47.3 | 11.8 | |

| 50-54 | Couple only | 79.3 | 66.0 | 11.5 | 3.4 | 37.6 | 1.7 |

| Couple with children | 84.2 | 68.4 | 14.5 | 5.8 | 45.5 | 22.7 | |

| One Parent with children | 64.9 | 51.3 | 4.3 | . | 25.1 | 17.6 | |

| Lone Male | 57.4 | 39.3 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 30.7 | 2.1 | |

| Lone Female | 66.0 | 56.7 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 29.5 | 3.0 | |

| All 50-54 | 76.6 | 62.0 | 10.7 | 3.9 | 38.7 | 12.0 | |

| 55-59 | Couple only | 72.6 | 63.9 | 7.7 | 3.3 | 23.7 | 1.0 |

| Couple with children | 77.7 | 62.9 | 9.7 | 4.9 | 30.1 | 24.8 | |

| Lone Male | 48.4 | 39.6 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 23.8 | 1.1 | |

| Lone Female | 60.4 | 50.3 | 4.8 | 2.3 | 25.6 | 1.0 | |

| All 55-59 | 69.4 | 58.8 | 7.1 | 3.5 | 25.8 | 7.8 | |

| 60-64 | Couple only | 63.7 | 59.2 | 3.9 | 1.5 | 10.2 | 0.1 |

| Couple with children | 74.6 | 59.4 | 8.9 | 3.8 | 21.9 | 22.6 | |

| Lone Male | 47.9 | 41.3 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 15.8 | ||

| Lone Female | 40.6 | 38.4 | 0.9 | 4.2 | 1.3 | ||

| All 60-64 | 59.4 | 53.2 | 3.9 | 1.5 | 11.9 | 4.1 | |

| All | Couple only | 72.8 | 63.3 | 8.2 | 2.8 | 25.2 | 1.0 |

| Couple with children | 84.4 | 70.4 | 13.3 | 5.4 | 44.4 | 20.4 | |

| One Parent with children | 68.9 | 50.9 | 2.9 | 0.5 | 33.9 | 14.1 | |

| Lone Male | 55.3 | 42.8 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 27.2 | 1.2 | |

| Lone Female | 57.1 | 49.7 | 4.2 | 1.2 | 23.6 | 2.8 | |

| All 45-64 | 73.2 | 61.4 | 8.8 | 3.4 | 33.2 | 9.5 | |

-

Note: The percentages represent the proportion of that group that have that form of debt. For example, 66.6% of Couple Only households with a reference person aged 45-59 have a credit debt. Any debt indicates that debt related to credit cards, rental property loans, investment loans, a mortgage or HECS is greater than zero. ‘Baby boomer’ households are colloquially defined here as those with a reference person aged 45 to 64 years.

-

Source: ABS 2003-04 Survey of Income and Housing unit record data.

The proportion of boomers in this 55 to 59 year age range who have a credit card debt ranges from a relatively austere 40 per cent for single male boomers to a maximum 64 per cent for boomer couples without children (Table 4). Boomer couples in this age range are more likely to have some form of debt than single boomers, with about half of all male single boomers aged 55 to 59 having some form of debt, about 60 per cent of female single boomers, and around three-quarters of all couple boomer households aged 55 to 59 having some form of debt.

As the lifecycle continues more manage to pay off their debts so that, at age 60 to 64, a majority of singles report that they do not have any debt. This is, of course, a crucial age group, as most are unlikely to earn much in the future and thus will have a reduced capacity to pay off debt as they enter old age. Again focusing on this 60 to 64 year age group, about two-thirds of couple households and about three-quarters of couple households with dependent children still at home report that they still have some debt. Only in a minority of cases is this still due to the struggle to pay off the mortgage on the family home, as only one-tenth of couples without children aged 60 to 64, one-fifth of couples with children and about one-sixth of single males are still paying off the family castle. Single females in their early 60s are even more likely to have paid off the mortgage, with only four per cent still logging mortgage repayments (Table 4).

Relatively few in their early 60s are paying off rental property or investment loans, with credit card debt being the most common form of debt for all baby boomers at all ages. The figures on HECS debts for some boomers might initially appear surprising, but the relatively high percentages recorded for couples with children and sole parents are clearly largely due to the debts of their children, rather than to their own HECS debts. Still, it is interesting that one in every 13 single baby boomer women aged 45 to 49 years old are still paying off their HECS debt, compared with only one in every 100 single baby boomer men of the same age. At ages 50 to 54 years, about two or three in every 100 baby boomer households without dependent children record a HECS debt repayment (Table 4).

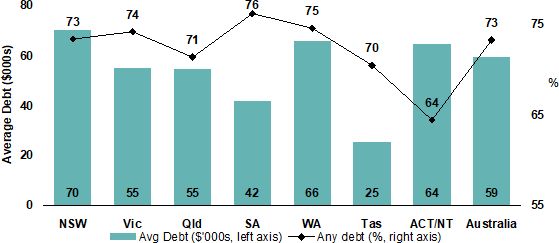

The average debt for all baby boomer households is an estimated $59,000 in 2004, with 73 per cent of the entire group recording some debt (Figure 5). South Australia stands out as the state or territory where the highest proportion of baby boomers have any form of debt (76%) – yet average debt levels are relatively low in SA, at only $42,000 per boomer household. On the other hand, the combined results for the ACT and Northern Territory show the lowest proportion of households reporting debt (64%) – but the one of highest average debts of $64,000 per household. This high average debt reflects the higher than average incomes of ACT residents. Sydney house prices are one of the factors driving the NSW results, with 73 per cent of NSW boomer households paying off debts and the average debt of all boomer households reaching $70,000.

Proportions of baby boomer households that have any form of debt and average amount of debt, by state/territory, 2004. Notes: Mixed households (for example two-family or group households) are excluded. ‘Baby boomer’ households are colloquially defined here as those with a reference person aged 45 to 64 years.Data source: ABS 2003-04 Survey of Income and Housing unit record data.

6. Baby boomers and spending

In addition to being comfortable with debt, the baby boomers are also famous for their spending and self-indulgence. But is this reputation accurate? In the next table we compare the baby boomers’ weekly spending with those of younger and older generations.

Incomes typically increase over the first half of the lifecycle, as individuals finish studying and start notching up more experience and promotions. But, as Table 5 shows us, the average incomes of households headed by 45 to 64 year olds are only very slightly higher than those of households with a head aged less than 45 years. This means that the average income results for the boomers are a mix of the relatively high incomes earned by those who are still working combined with the much lower incomes experienced by the early retirees among them.

Average weekly household expenditure by age of the reference person and type of expenditure, 2004

| Age of household reference person | All ages | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <45 years | 45-64 years | 65+ years | ||

| $ per week | $ per week | $ per week | $ per week | |

| Housing costs | 198 | 122 | 69 | 144 |

| Domestic fuel & power | 24 | 26 | 18 | 24 |

| Food & non-alcoholic beverages | 160 | 171 | 101 | 152 |

| Alcoholic beverages | 23 | 27 | 11 | 22 |

| Tobacco products | 12 | 13 | 4 | 11 |

| Clothing & footwear | 39 | 40 | 17 | 35 |

| Household furnishings & equipment | 62 | 56 | 29 | 53 |

| Household services and operation | 62 | 55 | 35 | 54 |

| Medical care & health expenses | 38 | 60 | 41 | 47 |

| Transport | 147 | 164 | 70 | 137 |

| Recreation | 120 | 132 | 71 | 114 |

| Personal care | 17 | 21 | 11 | 17 |

| Miscellaneous goods & services | 87 | 92 | 35 | 78 |

| Mortgage repayments-principal | 59 | 34 | 2 | 38 |

| Other capital housing costs | 94 | 66 | 16 | 68 |

| Superannuation & life insurance | 19 | 38 | 7 | 23 |

| Total expenditure | 1,163 | 1,117 | 535 | 1,016 |

| Total household Income from all sources | 1,253 | 1,270 | 540 | 1,111 |

-

Note: Total Expenditure includes selected other minor payments and may not be the sum of the items above. Income tax paid is not included within total expenditure. ‘Baby boomer’ households are colloquially defined here as those with a reference person aged 45 to 64 years.

-

Source: ABS 2003-04 Household Expenditure Survey unit record data.

After paying income tax, the total spending of boomer households and those headed by younger Australians aged less than 45 years is relatively similar – about $1120 a week for boomer households and $1165 a week for younger households (Table 5). The spending of older households, with a head aged 65 years and over, is roughly half that of working age households, at only $535.

The boomer households spend more each week than either younger or older households on food, alcohol, transport, personal care and miscellaneous goods and services (which include such items as rates, insurance, child and spouse maintenance payments and accountants fees). They spend about 50 per cent more than either older or younger households on medical care and health expenses, reflecting their poorer health status relative to younger households allied with their inability to access the more generous government health subsidies offered to those of age pension age. The $60 a week spent by boomer households on health products and services represents 5.4 per cent of their total after-tax spending, compared with only 3.3 per cent for younger households with heads aged less than 45 years.

As they ‘sea-change’ and ‘tree-change’, the boomers are spending more on recreation than either younger or older households — $132 a week for boomer households compared with $120 a week for younger households and $71 a week for households with heads aged 65 years and over. Recreation and entertainment thus account for about $12 in every $100 spent by the boomers.

Superannuation is another area of major difference between the generations, as the boomers save hard for the imminent retirement that awaits them. The boomers total spending on superannuation and life insurance of $38 a week is double that put away by younger households (Table 5) – but it is still less than one-third of their weekly spending on recreation and entertainment.

Other major lifecycle effects are also apparent. Younger households are spending far more on housing costs than either boomer or older households. In 2004, younger households were spending almost $100 a week in rent or mortgage interest and another $59 a week in paying off the mortgage principal on their home. These two items together chewed up more than one-fifth of the discretionary (after-tax) spending of households with heads aged less than 45 years. In contrast, boomer households were paying $122 a week in rent and mortgage interest and another $34 a week in chipping away at any remaining mortgage principal, with these two items together making up only 14 per cent of total boomer discretionary spending. Older households with heads aged 65 plus are spending only $71 a week on housing costs — and, as noted in the last AMP.NATSEM report on the characteristics of consumers in 2020, this and other differences mean that population ageing will have profound effects on the types of goods and services demanded by consumers in the future.

Moving now from the picture between the generations to exploring how different types of baby boomer households spend their money, Table 6 shows that couple with children boomer households spend many more dollars each week on housing, food, clothing, transport and recreation than other boomer households. In most cases, however, this simply reflects their greater purchasing power, as their incomes are 50 per cent higher than those of boomer couples and roughly three times as much as those of single boomers.

Average weekly household expenditure by baby boomer households by family type and type of expenditure, 2004

| Couple Only | Couple with Dependent Children | One Parent with Children | Lone Male | Lone Female | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $ per week | $ per week | $ per week | $ per week | $ per week | $ per week | |

| Housing costs | 101 | 149 | 124 | 104 | 110 | 122 |

| Domestic fuel & power | 26 | 33 | 26 | 17 | 17 | 26 |

| Food & non-alcoholic beverages | 156 | 246 | 156 | 72 | 71 | 171 |

| Alcoholic beverages | 28 | 36 | 11 | 23 | 7 | 28 |

| Tobacco products | 11 | 16 | 10 | 15 | 7 | 13 |

| Clothing & footwear | 34 | 62 | 50 | 6 | 18 | 40 |

| Household furnishings & equipment | 61 | 64 | 38 | 25 | 48 | 56 |

| Household services and operation | 51 | 73 | 52 | 26 | 36 | 55 |

| Medical care & health expenses | 70 | 72 | 39 | 31 | 29 | 60 |

| Transport | 155 | 233 | 123 | 71 | 77 | 165 |

| Recreation | 123 | 183 | 129 | 58 | 60 | 132 |

| Personal care | 20 | 30 | 15 | 3 | 13 | 21 |

| Miscellaneous goods & services | 72 | 142 | 84 | 42 | 36 | 92 |

| Mortgage repayments-principal | 23 | 52 | 21 | 26 | 22 | 34 |

| Other capital housing costs | 18 | 120 | 53 | 26 | 63 | 66 |

| Superannuation & life insurance | 57 | 38 | 13 | 18 | 17 | 38 |

| Total expenditure | 1004 | 1549 | 943 | 563 | 631 | 1119 |

| Total household income from all sources | 1101 | 1837 | 992 | 683 | 555 | 1271 |

-

Note: ‘Total Expenditure’ includes selected other payments and may not be the sum of the items above. Income tax paid is not included within total expenditure. ‘Baby boomer’ households are colloquially defined here as those with a reference person aged 45 to 64 years. Note that we believe that there is sampling error in the data for spending by female lone persons on capital housing costs (which includes extensions and renovations and the purchase of other investment properties). There are four outlying observations in the sample data for this group who spend between $2110 and $4251 a week on such capital housing costs: in contrast, there are no values over $2000 a week for single males. The estimates for ‘other capital housing costs’ should thus be treated with some caution, as should the total expenditure for single female households.

-

Source: ABS 2003-04 Household Expenditure Survey unit record data.

Boomer couples with children spend markedly less on superannuation than boomer couples without children. Many of these boomer couples without children are now in the ‘empty nest’ phase of the lifecycle, where they finally have the children off their hands and can afford to save harder for their retirement. Indeed, boomer couples without children are the standout performers in the superannuation saving stakes, devoting 4.7 per cent of their total spending to superannuation, compared with around 2 to 2 ½ per cent for couples with children and single boomers and only 1.2 per cent for boomer sole parents.

Single male boomer households confess to spending three times as much on alcohol and twice as much on tobacco as their female counterparts – although all these figures are no doubt affected by the well-known tendency to understate spending on ‘sin’ goods. However, the female single boomers spend four times more on personal care, three times as much on clothing and double on household furnishings.

7. Baby boomers and wealth

Of the estimated 11.6 million Australian adults living either as one of the partners in a couple or as a single adult household, 4.3 million are living in a household headed by a baby boomer. Despite the debt discussed above, these baby boomer households are estimated to be the wealthiest households in Australia. The average household headed by a baby boomer in 2004 had a net worth of $650,000. ‘Net worth’ is defined here as being the sum of the value of their assets — the family home and its contents, other property, money invested with financial institutions, shares, superannuation, vehicles, own incorporated business (net), and other assets— minus any debts (as discussed in the previous section).

The total wealth of different households can be misleading, however, as couple households typically have more wealth than single persons — but the likelihood of being part of a couple can vary systematically by age and the wealth of the couple potentially has to support two people in retirement rather than just one. Accordingly, we have calculated wealth per person, by dividing total household wealth in two when it is a couple household and leaving it untouched when it is a single person household.

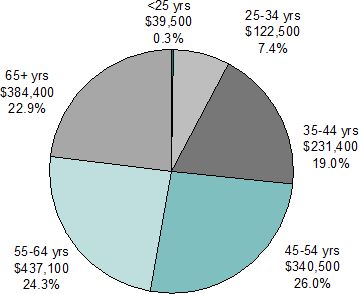

Using this definition, each baby boomer has on average accumulated a net wealth of $381,100. This average level of net worth for baby boomers compares with an average net wealth for all Australians of about $292,500 per person. Table 7 paints a clear picture of Australians accumulating wealth as they age, with per capita wealth increasing steadily as age increases up to retirement age. For example, average wealth is just $122,500 per person for those adults living in households headed by a 25 to 34 year old (Table 7).

Average per adult net worth, by age of the household reference person, Australia, 2004

| Age Group of H’hold Reference Person | Average Per Adult Net Worth | Share of total household net worth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Quartile (Poorest 25%) | 2nd Quartile | 3rd Quartile | 4th Quartile (Richest 25%) | Average within age group | ||

| $ | $ | $ | $ | $ | % | |

| <25 | 2,200 | 12,600 | 31,100 | 111,600 | 39,500 | 0.3 |

| 25-34 | 15,400 | 62,700 | 125,900 | 285,900 | 122,500 | 7.4 |

| 35-44 | 37,400 | 127,300 | 219,100 | 540,800 | 231,400 | 19.0 |

| 45-54 | 61,800 | 191,000 | 323,500 | 784,600 | 340,500 | 26.0 |

| 55-64 | 78,400 | 219,000 | 371,800 | 1,077,700 | 437,100 | 24.3 |

| All Baby Boomer Households | 68,300 | 202,300 | 342,500 | 910,400 | 381,100 | 50.3 |

| 65+ | 60,700 | 189,100 | 328,600 | 958,600 | 384,400 | 22.9 |

| All Households | 48,800 | 153,000 | 265,400 | 701,900 | 292,500 | 100.0 |

| Equity in Home (Value Per Adult) | ||||||

| All Baby Boomer Households | 29,400 | 114,100 | 179,700 | 320,300 | 161,000 | |

-

Note: The definition of net worth is based on the ABS definition. This definition includes more assets than were included in previous AMP.NATSEM Income and Wealth Reports. For example, the value of vehicles, contents of the home and collectibles were all previously excluded but are now part of the estimated net worth value. Mixed family households (for example two-family or group households) are excluded. ‘Baby boomer’ households are colloquially defined here as those with a reference person aged 45 to 64 years. Each single person or partner within a couple household within each age range is ranked by their per adult net worth and then assigned to an age-specific wealth quartile. The poorest 25% of adults within an age band are assigned to Quartile 1 and the richest 25% to Quartile 4. The technical notes contain more details. The quartiles are within the specified age groups.

-

Source: ABS 2003-04 Survey of Income and Housing unit record data.

The final right hand column of Table 7 shows the results when we add up the wealth of all the adults in Australian households (excluding mixed households and not counting any older dependent children still living in the parental home as ‘adults’). This shows that baby boomer households possess half of total household wealth (50.3%), even though such households contain only 37 per cent of all adults considered in our analysis. Households headed by an older Australian aged 65 years and over hold almost another quarter (22.9%) of the total household wealth in our society (Figure 6). Similarly, those headed by a 35 to 44 year old hold about one-fifth of total household wealth.

Average per adult net worth and share of total household net wealth held, by age of household head, 2004. Notes: Mixed households (for example two-family or group households) are excluded from this analysis. A definition of ‘net worth’ is provided in the technical notes. The percentages in the figure are shares of total wealth. Looking at population shares rather than wealth shares, 3% of adults (excluding dependent children) live in a household headed by a person under 25 years of age, 17% in a household headed by a 25-34 year old, 23% by a 35-44 year old, 22% by a 45-54 year old, 16% by a 55 to 64 year old, and 19% by a 65+ year old.Data source: ABS 2003-04 Survey of Income and Housing unit record data.

Table 7 also looks at the average wealth held in the form of the family home, by quartile. It shows that, on average, baby boomers have accumulated $161,000 per person through home ownership. Thus 42 per cent of the wealth held by baby boomer households is held in the form of their family home. For baby boomers in the middle of the net worth spectrum, the proportion is even higher (Quartile 2: 56%; Quartile 3: 53%).

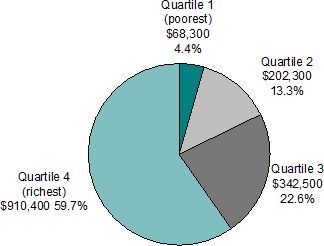

Wealth, however, is far more unequally distributed than income — so looking at the average wealth of particular age groups can be very misleading. In the case of boomers, for example, the least wealthy one-quarter of baby boomers (called Quartile 1) have an average per adult wealth of only $68,300 (Figure 7 and Table 7). In contrast, the average personal net worth of the wealthiest one-quarter of boomers is over $900,000. This is 13 times the average of the poorest quartile. It means that the poorest one-quarter of baby boomers possess 4.4 per cent of the group’s net worth while the wealthiest one-quarter enjoy 60 per cent of the boomers’ $1,648 billion net worth.

Share of wealth held by baby boomers and average per adult net worth, by baby boomer wealth quartile, 2004. Notes: Mixed households (for example two-family or group households) are excluded. Only baby boomer households are considered in scope, with ‘baby boomer’ households here being colloquially defined as those with a reference person aged 45 to 64 years. Each single person or partner within a couple household within this ‘baby boomer’ age range is ranked by their per adult net worth and then assigned to a baby boomer wealth quartile. The poorest 25% of adults are assigned to Quartile 1 and the richest 25% to Quartile 4.Data source: ABS 2003-04 Survey of Income and Housing unit record data

The spread of wealth across Australian society is also very wide, ranging from around $49,000 per adult for the poorest one-quarter of adults to just over $700,000 for the wealthiest one-quarter (Table 7).

Another view of the wealth of baby boomers is by the type of household that they live in. As above, all those adults living in boomer households were assigned to a boomer wealth quartile, and then the type of household that they live in was examined. Table 8 shows, for example, that four in ten (41.2%) of all ‘One Parent’ baby boomers are in the poorest wealth quartile. ‘Lone Male’ and ‘Lone Female’ are also over-represented in the poorest quartile.

Distribution of baby boomers, by wealth quartile and type of household, Australia, 2004

| Household Type | Average Net Worth Quartile | Share of Adults | Share of Net Worth | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Quartile (Poorest 25%) | 2nd Quartile | 3rd Quartile | 4th Quartile (Richest 25%) | |||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Couple only | 22.2 | 25.8 | 24.9 | 27.1 | 37.1 | 44.1 |

| Couple with children | 22.7 | 26.5 | 27.0 | 23.9 | 46.1 | 48.3 |

| One Parent with children | 41.2 | 18.3 | 18.3 | 22.1 | 2.5 | 1.1 |

| Lone Male | 36.7 | 18.7 | 20.0 | 24.6 | 7.1 | 3.4 |

| Lone Female | 36.6 | 19.3 | 21.1 | 23.0 | 7.2 | 3.2 |

| All | 25.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

-

Notes: Mixed households (for example two-family or group households) are excluded. ‘Baby boomers’ are defined here as those adults living in a household with a reference person aged 45-64 (excluding older dependent children still living in the parental home). Each single person or partner within a couple household within this ‘baby boomer’ age range is ranked by their per adult net worth and then assigned to a baby boomer wealth quartile. The poorest 25% of adults are assigned to Quartile 1 and the richest 25% to Quartile 4.

-

Source: ABS 2003-04 Survey of Income and Housing unit record data.

Conversely, Table 8 shows that couples are over-represented in the rich quartiles and underrepresented in the poorest one-quarter. The effect of this distribution towards people in couple households being wealthier than people in single parent households, allied with the large number of couples in this age group, sees more than 92% of the wealth of the boomer group being controlled by couple households.

Another important question is whether the wealth of the boomers will provide them with enough income in retirement or is it all held in cars, their own home and castle, and plasma TVs? In previous AMP.NATSEM reports, we have examined the potential difficulties created when wealth is disproportionately held in the family home, which can be traumatic to tap into when money is needed to fund day-to-day living expenses in retirement.

To examine this we need to look at the financial assets of the household.4 These financial assets either provide a source of income or can be readily drawn-down to provide a more comfortable standard of living in retirement. Table 9 suggests that such ‘actually or potentially liquid assets’ on average increase across the working years, rising from $7,800 per adult for those living in households headed by an Australian aged less than 25 years to $136,900 for older baby boomers living in households headed by a person aged 55 to 64 years. Again, there is a wide gulf between the poorest and the richest. For example, concentrating again on adults living in households headed by a 55 to 64 year old, the poorest one-quarter have average financial assets of $16,800 each, while the most affluent one-quarter have financial assets of just under $373,600 per adult.

Average financial assets per adult, by age of the household reference person, Australia, 2004

| Age Group of H’hold Ref Person | Average net worth per person quartile | Share of total household financial assets | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Quartile (Poorest 25%) | 2nd Quartile | 3rd Quartile | 4th Quartile (Richest 25%) | Average within age group | ||

| $ | $ | $ | $ | $ | % | |

| <25 | 1,300 | 4,400 | 8,100 | 17,400 | 7,800 | 0.3 |

| 25-34 | 7,200 | 18,500 | 25,200 | 55,600 | 26,600 | 5.8 |

| 35-44 | 11,000 | 29,700 | 45,100 | 118,000 | 51,000 | 15.3 |

| 45-54 | 14,800 | 44,900 | 86,100 | 235,200 | 95,300 | 26.6 |

| 55-64 | 16,800 | 45,100 | 111,600 | 373,600 | 136,900 | 28.0 |

| 65+ | 10,200 | 31,300 | 67,600 | 328,500 | 109,500 | 24.0 |

| All | 11,700 | 33,100 | 64,300 | 210,200 | 79,900 | 100.0 |

-

Notes: Mixed households (for example two-family or group households) are excluded. The quartiles are based on per person net worth within each age group (that is, the quartiles are the same as those used in Table 7). Each single person or partner within a couple household within each age range is ranked by their per adult net worth and then assigned to an age-specific quartile. The poorest 25% of adults within an age band are assigned to Quartile 1 and the richest 25% to Quartile 4.

-

Source: ABS 2003-04 Survey of Income and Housing unit record data.

8. Conclusions

Five years of strong economic growth and extensive publicity about the need to ‘work longer, save harder’ have resulted in more baby boomers finding and keeping jobs. There have been some striking increases in labour force participation rates by older baby boomers — and these will help the boomers to fund their forthcoming retirement.

Yet, despite these positive trends, it is still apparent that many baby boomers are retiring early. For example, by age 55 to 59 years, one in every five married and two in every five unmarried baby boomer males have already quit the labour force. For baby boomer women, two in every five are out of the labour force by age 55 to 59. By age 60 to 64, the majority of both married and unmarried women and of unmarried men have retired.

Many baby boomers are entering early retirement while still having debt hanging over their heads. The total debt of baby boomer households is estimated at a hefty $150 billion. The average debt for all baby boomer households is an estimated $59,000 in 2004, with 73 per cent of the entire group recording some debt.

The good news is that boomers are managing to reduce their debt levels as they approach the official retirement age. At age 60 to 64, less than half of all single boomers, about two-thirds of couple households and about three-quarters of couple households with dependent children still at home report that they still have some debt. Only in a minority of cases is this still due to the struggle to pay off the mortgage on the family home; looking just at 60 to 64 year olds, only about one-tenth of singles and couples without children and one-fifth of couples with children are still paying off the mortgage.

Roughly four in every five baby boomer households have leapt the home purchase hurdle, giving most a comfy base for their forthcoming decades of retirement. The boomers are also socking away superannuation, with their average spending on superannuation and life insurance of $38 a week being double the amount put away by younger households – although it is still less than one-third of their weekly spending on recreation and entertainment!

The baby boomer households control one half of all household wealth. On average, they have accumulated a net worth of $381,100 per person. However, just under half of this is through home ownership, with this resource perhaps being more difficult to tap into to fund a comfortable retirement. The least wealthy one-quarter of baby boomers have each amassed only a relatively modest $68,000 in net worth — while the wealthiest one-quarter are sitting on personal nest eggs worth just over $900,000 on average.

Footnotes

1.

Married is defined as living as a member of a couple with or without dependent children

2.

The labour force participation of people between the ages of 45 and 54 does not vary significantly and these two age groups have been amalgamated in the following discussion.

3.

The minimum female eligibility age for the Age Pension was 60 years in 1986, 60.5 years in 1996 and 63 years in 2006. The male eligibility age is 65 years.

4.

Financial assets are the sum of the accounts held with financial institutions, the value of other property, trusts, shares, superannuation, debentures & bonds, and own incorporated business (net).

Appendix

Technical notes and definitions

ABS data

Much of the data used in this report is drawn from the Household Expenditure Survey and Survey of Income and Housing for 2003-04. The Australian Bureau of Statistics releases this data to academics in a confidentialised format, which ensures that individuals cannot be identified. About 7000 households took part in the survey.

Household reference person

The ABS select the reference person for each household by applying the selection criteria below to all household members aged 15 years and over in the order listed until a single appropriate reference person is identified:

one of the partners in a registered or de facto marriage, with dependent children

one of the partners in a registered or de facto marriage, without dependent children

a lone parent with dependent children

the person with the highest income

the eldest person. For example, in a household containing a two non-related people, the one with the higher income will become the reference person. However, if both individuals have the same income, the elder will become the reference person.

Net worth per adult

To present a picture of net worth and financial assets that is not biased towards couple households, the value of net worth and financial assets has been divided by the number of adults present in the household. The effect of this is to halve the assets of couples. Multiple family households and group households have been excluded from the calculation. Where there are adult dependent children still living at home, they have not been assigned any of the household assets. That is, for single person households their net worth is the same as their household net worth while, for couple households, the total household net worth has been split equally between the two partners in the couple.

Net worth

The definition of net worth is broader than the definition of wealth used in earlier AMP.NATSEM reports. While it is still defined as the difference between assets less liabilities, it is defined on a household basis (including children’s assets) and there are a greater range of assets and liabilities.

Assets:

The assets are the value of accounts held with financial institutions, owner occupied dwelling, other property, trusts, shares, superannuation, debentures & bonds, own incorporated business (net), contents of dwelling, vehicles and other assets.

Liabilities:

The liabilities are the principal outstanding on loans for owner occupied dwelling, other property, investment loans, loans for vehicle purchases, loans other purposes, amount owing on credit cards, debt outstanding on study loans

The net worth in this report differs from published ABS figures as a number of household groups have been removed from the data used in some sections this report. For example, single parent households aged 55 and over were removed and multi-family households were removed.

In many cases per capita net worth is shown in the tables, so that a more accurate comparison can be made between the circumstances of couples and singles. In these cases, the net worth of couples has been split equally between the two of them.

Financial Assets

Financial assets have been used to show the household value of assets that either produce income or can be easily converted to cash. Essentially it removes the family home, vehicles, and the value of the contents of the home from net worth. This means the definition of ‘financial assets’ is the sum of the value of accounts held with financial institutions, the value of other property, trusts, shares, superannuation, debentures & bonds, and own incorporated business (net).

This report was written by Simon Kelly and Ann Harding from the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling Pty Limited ('NATSEM'), and published by AMP. This report contains general information only and although the information was obtained from sources considered to be reliable, the authors, NATSEM and AMP do not guarantee that it is accurate or complete. Therefore, readers should not rely upon this information for any purpose including when making any investment decision. Except where liability under any statute cannot be excluded, NATSEM, AMP and their advisers, employees and officers do not accept any liability (where under contract, tort or otherwise) for any resulting loss or damage suffered by the reader or by any other person.

Housing tenure of baby boomers by type of household, Australia, 2004

| Household type and age group of reference person | Tenure | Total homeowners | Outright owners as proportion of homeowners | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner without mortgage | Owner with mortgage | Renter | Other | |||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Couple Only | ||||||

| 45-49 | 35.5 | 43.3 | 21.2 | - | 78.8 | 45.1 |

| 50-54 | 50.8 | 37.4 | 11.1 | 0.8 | 88.2 | 57.6 |

| 55-59 | 65.7 | 23.7 | 9.3 | 1.3 | 89.4 | 73.5 |

| 60-64 | 81.5 | 9.6 | 6.5 | 2.3 | 91.1 | 89.5 |

| Couple with children | ||||||

| 45-49 | 35.3 | 52.9 | 10.1 | 1.8 | 88.2 | 40.0 |

| 50-54 | 43.5 | 45.4 | 10.1 | 1.0 | 88.9 | 48.9 |

| 55-59 | 57.9 | 30.1 | 11.2 | 0.8 | 88.0 | 65.8 |

| 60-64 | 66.6 | 21.9 | 10.5 | 1.1 | 88.5 | 75.3 |

| One Parent | ||||||

| 45-49 | 18.7 | 37.2 | 39.8 | 4.3 | 55.9 | 33.5 |

| 50-54 | 28.8 | 25.1 | 41.5 | 4.6 | 53.9 | 53.4 |

| Lone Male | ||||||

| 45-49 | 29.3 | 34.5 | 34.8 | 1.3 | 63.8 | 45.9 |

| 50-54 | 25.7 | 30.7 | 43.1 | 0.5 | 56.4 | 45.6 |

| 55-59 | 40.2 | 23.8 | 32.1 | 3.9 | 64.0 | 62.8 |

| 60-64 | 52.3 | 14.4 | 28.4 | 4.8 | 66.7 | 78.4 |

| Lone Female | ||||||

| 45-49 | 21.3 | 40.4 | 36.9 | 1.4 | 61.7 | 34.5 |

| 50-54 | 32.7 | 29.5 | 35.2 | 2.6 | 62.2 | 52.6 |

| 55-59 | 42.7 | 25.6 | 29.8 | 1.9 | 68.3 | 62.5 |

| 60-64 | 66.2 | 3.5 | 28.2 | 2.1 | 69.7 | 95.0 |

| ALL | ||||||

| 45-49 | 31.9 | 47 | 19.5 | 1.7 | 78.9 | 40.4 |

| 50-54 | 41.4 | 38.7 | 18.7 | 1.3 | 80.1 | 51.7 |

| 55-59 | 57.1 | 25.8 | 15.5 | 1.6 | 82.9 | 68.9 |

| 60-64 | 72.4 | 11.2 | 13.9 | 2.4 | 83.6 | 86.6 |

| All Baby boomers | 48.1 | 33 | 17.3 | 1.7 | 81.1 | 59.3 |

-

Notes: Mixed households (for example two-family or group households) are excluded from the data above.The sample sizes were too small to provide reliable estimates for one parent households with the reference person aged 55+ and this group has been excluded from the table above.‘Baby boomer’ households are colloquially defined here as those with a reference person aged 45 to 64 years. All of the results are for households.

-

Source: ABS 2003-04 Survey of Income and Housing unit record data.

References

-

1

Technical Paper, Information PaperHousehold Expenditure Survey and Survey of Income and Housing - Confidentialised Unit Record Files, Technical Paper, Information Paper, ABS Cat no.6540.0.00.001, Canberra, June.

-

2

Labour Force, Australia, Detailed - Electronic DeliveryLabour Force, Australia, Detailed - Electronic Delivery.

- 3

-

4

Modelling Our Future: Population Ageing, Social Security and Taxation (Eds), International Symposia in Economic Theory and EconometricsMacroeconomic Effects of Proposed Pension Reforms in Norway, Modelling Our Future: Population Ageing, Social Security and Taxation (Eds), International Symposia in Economic Theory and Econometrics, North Holland, Amsterdam.

-

5

Economic Implications of an Ageing AustraliaSSRN Electronic Journal, 10.2139/ssrn.738063.

- 6

- 7

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

No specific funding for this article is reported.

Publication history

- Version of Record published: August 31, 2023 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2023, Lloyd et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.