Accounting for Behavioral Effects in Microsimulation: A Reduced Form Approach

- Article

- Figures and data

-

Jump to

- Abstract

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Behavioral and non-behavioral microsimulation modeling

- 3. A simple procedure for accounting for changed incentives

- 4. Policy change used in the empirical illustration

- 5. Simulation results

- 6. Conclusion

- Footnotes

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Appendix C

- References

- Article and author information

Abstract

Microsimulation models are used worldwide to assist in the policy-making of governments. The simulation models may be purely non-behavioral or they may also include modules that simulate labor supply responses to the policy change in question. The present paper demonstrates how the practitioner can employ exogeneously given response estimates to account for behavioral effects in this type of work. Response estimates are combined with individual changes in work incentives at both the extensive and intensive margins. The concepts of the participation tax rate (PTR) and the effective marginal tax rate (EMTR) are employed. In the empirical illustration we discuss distributional and social welfare effects arising from the changes in Finnish taxes and benefits that took effect in 2020.

1. Introduction

Description of revenue and distributional effects of changes in tax-benefit schemes are routinely produced by policy analysts by the use of microsimulation models. Although tax-benefit changes are known to induce behavioral changes, for example in labor supply, the calculations are still, however, often non-behavioral. One important reason for this is that establishing a simulation tool based on a structural model is demanding, both with respect to finding suitable data and with respect to handling econometric challenges.

It adds to the complications that no clear consensus exists on how structural labor supply models should be designed. The discrete choice model of labor supply, based on stochastic utility theory have gained widespread popularity, mainly because it is much more practical than the conventional continuous approach, based on marginal calculus, see the surveys by Creedy and Kalb (2005), and Dagsvik et al. (2014). However, still the policy analyst may find it challenging to establish such a tool. It also belongs to the picture that it has been raised some concern about the ability of structural models to generate robust predictions about the effects of policy changes, see LaLonde (1986), and Imbens (2010).

The present study demonstrates a way forward for the public policy analyst who wants to take behavioral effects into account in the answers delivered to the policy-makers, but who is reluctant to enter into the uncharted waters of labor supply modeling. The paper shows how the practitioner of microsimulation may employ exogenously given elasticity estimates in practical work, which we refer to as a non-structural reduced form approach, using relevant elasticities from the literature, either from structural studies or from quasi-experimental analyses. With respect to the latter category, quasi-experimental estimates along the intensive margin of responses typically refer to elasticities of taxable income (ETI), see reviews of the ETI literature in Saez et al. (2012) and Neisser (2021). The ETI captures not only working hours responses but may also reflect effects of other response margins, which may all lead to changes in government revenue. The ETI is seen as a sufficient statistic of the intensive margin responses for existing tax systems (Chetty, 2009). Similarly, extensive margin responses are obtained by quasi-experimental studies that focus on employment effects of tax and benefit policy changes. By employing exogeneously given response estimates the identification of behavioral effects is transparent and flexible, allowing for different assumptions regarding the behavioral response. However, as argued by Kleven (2021), discussing social welfare effects of policy employing reduced-form evidence, such as employing elasticity estimates under the so-called sufficient statistics approach to policy evaluation, hinges on relatively strong assumptions. One critical concern is external validity, i.e., to which extent findings of a study can be generalized to other contexts. Another important question is whether all relevant social effects (due to the policy change) are included in the estimate at hand.

The procedure suggested here is related to the method demonstrated by Immervoll et al. (2007), but instead of estimating behavioral effects by subgroups, such as income deciles, our empirical strategy is based on individual-level information combined with average elasticities. We predict individual earnings levels, which are obtained through Mincer-type regressions. Next, response heterogeneity is achieved by obtaining individual measures for changes in the participation tax rate (PTR), for the extensive margin, and changes in the effective marginal tax rate (EMTR), for the intensive margin. Then we employ (average) elasticity estimates from the literature, which do not vary across individuals,1 for responses both at the extensive and intensive margins. See also Jia et al. (2023) for a related study.

Our paper differs from the existing work by offering a unified framework that incorporates both extensive and intensive margin elasticities into otherwise static microsimulation models to study the impacts of policy reforms on employment, the distribution of income, and social welfare. We also demonstrate the flexibility of the proposed procedure by using different specifications, for instance with respect to the choice of labor supply elasticity estimate.

We illustrate our procedure by discussing distributional and welfare effects of Finnish tax-benefit changes of 2020. The changes include increases of multiple social benefits and tax credits, however, without any major reform. Such incremental policy changes represent the type of analysis that the practitioner of microsimulation often is asked to predict the results of or to evaluate outcomes of. Thus, the policy change under investigation here serves as a practical example of the type of changes in the tax-benefit scheme that the policy analyst typically faces. Additionally, these kind of policy reforms are the most suitable ones for our approach as larger reforms would require adding more structure to the method (for example, specifying the utility function; see the discussion in Kleven, 2021).

The Finnish national tax-benefit microsimulation model SISU (Statistics Finland, 2020) is used to calculate the non-behavioral effects, which, given our main message here, can be expanded by adding results from a module calculating the behavioral effects, based on exogenously given response estimates. The simulation model is based on administrative micro data that represents Finnish population at the end of 2017. With respect to output, the main focus is on distributional effects, but we also illustrate how results can be summarized in terms of an abbreviated social welfare function, as discussed by Foster and Sen (1997) and Lambert (2001), and applied by, for example, Creedy et al. (2020).

The rest of the paper is constructed as follows: Section 2 describes the components of the empirical framework: the microsimulation model, the alternatives the practitioner face for incorporating behavioral responses, and how to describe outcomes. Further in Section 3, we specify how, by the use of the PTR and EMTR concepts, we obtain individual response estimates. Section 4 presents the policy change used to illustrate the framework, whereas Section 5 presents results of the policy changes, measured by employment changes, income distributional effects, and effects on welfare. Section 6 concludes.

2. Behavioral and non-behavioral microsimulation modeling

2.1. The SISU model of Finland

Practical policy-making is often assisted by employing tax-benefit microsimulation models. We find such modeling tools in most developed countries, including the US (NBER’s TAXSIM), the UK (IFS’s TAXBEN and UKMOD by the University of Essex), Australia (Melbourne University’s MITTS), New Zealand (Treasury’s TaxWell), Sweden (Statistics Sweden’s FASIT), Denmark (Treasury’s Lovmodellen), and Norway (Statistics Norway’s LOTTE), and models incorporating multiple countries (such as the EUROMOD), to name just a few. Some of these models are non-behavioral (or arithmetic), whereas others include behavioral labor supply modules, which have been developed in interplay with the non-behavioral model. For example, in Norway, Statistics Norway has developed two sub-models to assist the policy-making process, belonging to the LOTTE family of models; the non-behavioral LOTTE-Skatt and a labor supply module, LOTTE-Arbeid, see (Aasness et al., 2007).2 Although there are several response margins that are potentially important to account for, given changes in the tax-benefit scheme, a main focus of behavioral microsimulation is the labor supply dimension and how responses affect income.

The main contribution of the present paper is to explain how one may proceed in order to account for behavioral effects in a microsimulation context, adding to results from a non-behavioral simulation, but relying on response estimates from the literature (a reduced form approach), not on a fully developed structural behavioral simulation model. Given our focus on Finnish policies, the point of departure is the non-behavioral Finnish tax-benefit model SISU (Statistics Finland, 2020). The model is maintained by Statistics Finland and is used widely by ministries, universities and governmental research institutes.

The model is based on extensive administrative data that is compiled for a random population sample of approximately 800,000 individuals, i.e., 15 percent of the Finnish population at the end of 2017. The model can be characterized as a standard non-behavioral microsimulation model or a tax-benefit model. There are examples of previous studies accounting for behavioral responses at the extensive margin in connection to the model (Kotamäki et al., 2018; Kärkkäinen and Tervola, 2018).

As data of microsimulation models often are from another year than the simulations are carried out for, a practical question is how policy parameters (and data) are projected to the year in question. At least three adjustment methods can be used: 1) adjustment with a wage index; 2) adjustment with the consumer price index; or 3) effects of juridical change. More discussion of such methods are provided in Adam et al. (2015) and Paulus et al. (2020). In the following we obtain results by using the consumer price index for the projections of policy parameters. It is, however, important to note that our analysis does not incorporate any now-casting techniques into the data. For more information about now-casting or updating of data in the microsimulation context, we refer to O’Donoghue and Loughrey (2014).

2.2. Accounting for behavioral responses

2.2.1. Several sources to evidence on labor supply response

In this section we review the literature on labor supply effects and responses in income to changes in tax-benefit policies. The ambition is to point out response estimates that can be used in the empirical investigation. In principle, these chosen estimates may come from any study, independent of the empirical approach, but, of course, the choice of response estimates is guided by assessment of the setting of which they are derived; i.e., to which extent the result of a study can be applicable to other settings, and in particular to the setting of the present study. In practice, this means that the chosen estimates must also be qualified by their placement in the literature and their relation to consensus estimates.

Although several informative surveys have recently been produced, see Blundell and MaCurdy (1999), Keane (2011), Saez et al. (2012), Chetty et al. (2013), and Bargain and Peichl (2016), it is not easy to obtain a clear and convincing picture of how taxpayers respond to economic incentives, such as changes in wages and taxes. Elasticities are derived in static frameworks, referred to as steady-state elasticities Chetty et al. (2013) and from various types of life-cycle models, they are obtained from macro and micro data, and the empirical evidence may come from quasi-experimental studies as well as from estimations of structural models.

One important avenue of research is based on structural steady-state approaches, which neglect the intertemporal aspects of optimization. In this approach the individual agent is assumed to have preferences over total consumption and leisure and to maximize utility under the economic budget constraint determined by the wage, non-labor income and the tax system. The so-called Hausman-approach (Burtless and Hausman, 1978; Hausman, 1981) departs from a linear labor supply function to handle piecewise linear budget constraints. Estimations are carried out both with positive and zero working hours, which means that estimates for both intensive and extensive margin can be obtained.

Estimation of structural labor supply models associated with the Hausman-approach is often complicated. The post-Hausman literature includes two lines of research which can be considered as replies to the complexities of the Hausman-model. First, discrete choice models of labor supply, based on stochastic utility theory, have gained widespread popularity, mainly because they are much more practical than the conventional continuous approach based on marginal calculus (van Soest, 1995; Creedy and Kalb, 2005; Dagsvik et al., 2014). The discrete choice approach differs from the corresponding continuous one (as in the Hausman-model) because the set of feasible hours of work is approximated by a suitable finite discrete set, making it easy to deal with non-linear and non-convex economic budget constraints. From a theoretical perspective, however, the conventional discrete choice model is similar to the standard textbook approach to labor supply in that it is essentially a version of the theory of consumer behavior. With particular distributional assumptions about the stochastic disturbances in the utility function one can derive tractable expressions for the distribution of hours of work, such as the multinomial logit model or the nested multinomial logit model. Elasticity estimates are conventionally obtained by simulations, for example measuring working hours when all before-tax wages are increased by 1 or 10 percent. Narazani et al. (2021) is a recent example of a behavioral microsimulation model building on the discrete choice framework.

A second post-Hausman development is the branch of the literature that utilizes tax reforms in order to identify labor supply responses. In particular, after an initial contribution by Feldstein (1995), a large literature has developed techniques to obtain estimates of the elasticity of taxable income (ETI), using tax reforms as quasi-experiments, see Saez et al. (2012) and Neisser (2021) for surveys of the literature. The identification of responses comes from comparing income before and after a change in the tax scheme (tax reform), often using data from income tax returns. This line of research is in particular founded on two methodological moves, compared to the earlier literature. First, instead of focusing on effects on working hours, it predominantly measures effects with respect to taxable income. Therefore, it has been argued that results seize all the policy relevant behavioral adjustments of a tax change at the intensive margin. Second, econometric identification is often based on attributing the change in reported income to the change in the effective marginal tax rate and exploiting the fact that tax reforms often affect different parts of the income distribution differently. The latter means that one often uses the difference-in-differences estimator, by letting the group less (or not at all) affected by the tax change serve as a control group, representing (unobserved) income changes in the affected group, absent the tax reform.3 This framework has been utilized to obtain tax responses from reforms in a number of countries. However, compared to the structural approach, response estimates are to larger extent dependent on the setting of which the estimates are derived. They are "history dependent" in the sense that responses reflect the actual tax reform used to obtain identification. This means that the external validity, i.e., the relevance of estimates for the development of new policies, must be discussed case by case.

Furthermore, some argue that tax elasticity estimates should preferably be derived from macro data instead of micro data (Mertens and Montiel Olea, 2018). Mertens and Montiel Olea (2018) discuss both short-run (steady-state) and long-term elasticity estimates, results are derived from aggregate data over a number of tax reforms in post-war U.S., and macro econometric techniques are used in the identification. Interestingly, the elasticity estimates are clearly larger than most estimates of the conventional ETI literature (based on micro data), which is explained by additional efforts to control for dynamics, such as expectations and endogeneity of tax policies.4

Finally, it is important to note that there is variation in the literature with respect to whether uncompensated (Marshallian) or compensated (Hicksian) elasticities are reported. In Gruber and Saez (2002) it is argued that the ETI represents a compensated effect, under the assumption that the income effect is close to zero.

2.2.2. Participation elasticity

In terms of the extensive margin elasticity, we use the participation elasticity, which reflects the percentage increase in employment when the financial gain from work (the difference of disposable income when working versus being out-of-work) increases by one percent. The empirical literature of extensive margin elasticities has shown that the behavioral labor supply responses differ between population groups. Women and individuals with lower incomes or lower level of education are often found to have higher elasticities compared to men and individuals with high-incomes or higher level of education. Elasticities also differ with respect to having children and marital status. However, the literature is not unanimous regarding the actual level of the participation elasticity.

Lundberg and Norell (2020) review the literature that estimates the participation elasticity using quasi-experimental methods. In total, their survey consists of 35 research papers based on data from many European countries and the United States. They conclude that the overall participation elasticity is likely to be below 0.36 and their preferred estimate lies between 0.1 and 0.2. This is in line with earlier surveys of the quasi-experimental participation elasticity literature, see Chetty et al. (2011b) and Chetty et al. (2013), which conclude by referring to an Hicksian elasticity of 0.25 for the extensive margin and 0.3 for the intensive margin.

Studies analysing the 1993 EITC reform in the USA find significant labor supply reactions, see (Hotz and Scholz, 2003, Hotz and Scholz, 2003, Eissa and Hoynes, 2006, Eissa and Hoynes, 2006, and Nichols and Rothstein, 2015), but these estimates have been recently questioned by Kleven (2024). Kleven finds that the large labor supply reactions are mostly due to confounding factors occurring at the same time with the reforms.

Fairly low values of extensive margin elasticities have been obtained in recent European studies as well. Thoresen and Vattø (2015), based on a structural labor supply model, refer to estimates around 0.2 for single males and married/single females and close to 0 for married males. Bastani et al., 2021, based on Swedish data, find an average participation elasticity of 0.13 for married females.

With respect to evidence based on Finnish micro data, Jäntti et al. (2015) estimates an average participation elasticity of 0.17, with very similar estimates for males (0.173) and females (0.163). Evidence from the Finnish basic income experiment, see Verho et al. (2022), supports low responses. Also, Bargain and Orsini (2006) and Bargain et al. (2014) find rather small participation elasticities for Finland. In these two studies, elasticity estimates for females range from 0.12 to 0.26, and for males, from 0.10 to 0.34, depending on marital status. However, Kosonen (2014) obtains a large participation elasticity, of 0.8, for a very specific group: mothers with small children.

Based on the literature reviewed above, we decide to use a participation elasticity of 0.2. This is in line with the recent survey by Lundberg and Norell (2020) and very close to the estimated elasticity for Finland in Jäntti et al. (2015). However, as Bargain and Peichl (2016) emphasize, there is no "right" elasticity parameter and therefore we run robustness checks with participation elasticities of 0.1 and 0.3. Finally, we add heterogeneity in participation elasticity by gender and the age of the youngest child, to test the robustness of our findings (see Appendix B for full details).

2.2.3. Intensive margin elasticity

Given the empirical strategy proposed by the present study, using exogenously given response estimates to take behavioral responses into account, we emphasize that behavioral response estimates of the literature differ along several dimensions. First, they differ with respect to which behavioral response margins that are addressed – the intensive or extensive margins. Second, they differ which groups’ responses that are considered, for example, with respect to age, gender, occupation, etc. Third, estimates may come from studies based on various methodologies, such as evidence based on quasi-experiments and structural models.5 Given quasi-experimental evidence, it is worth noting that both the difference-in-differences method, as seen in Feldstein (1995) and Gruber and Saez (2002), and identification through bunching approaches, see review of the method in Kleven (2016), can be used.

At the intensive margin, we employ an elasticity estimate mainly based on contributions to the elasticity of taxable income (ETI) literature. The ETI measures the percentage change in taxable income resulting from a one percent change in one minus effective marginal tax rate. This notion encapsulates both hours choices and changes in efforts, which may be reflected in hourly wages. It may also entail effects stemming from tax avoidance or evasion. According to a recent meta-analysis, conducted by Neisser (2021), the majority of ETI estimates fall within the range of 0 to 1, with a significant concentration around 0.3. Similarly, Saez et al. (2012) conclude that the best available estimates of the long-run elasticity range from 0.12 to 0.4, and likely smaller in the short-term.

Based on Finnish data, Matikka (2018) obtains an elasticity of 0.21, when exploiting the variation in municipal taxation in the identification. Results from other Nordic countries are relatively close to the findings of Matikka. (Kleven and Schultz, 2014) studies several Danish tax reforms and finds an average estimate of 0.12. Chetty et al. (2011a) also uses Danish data and does not find strong labor supply responses. With Norwegian data, Thoresen and Vattø (2015) find elasticity estimates below 0.1, whereas Blomquist and Selin (2010) use Swedish tax reforms and identify estimates in the range between 0.19 and 0.21 for males and between 0.96 and 1.44 for females.

Our choice of response estimate is 0.2, which is very close to the main estimate of Matikka (2018). Again, we use elasticity estimates of 0.1 and 0.3 to check the robustness of our results with respect to choice of response estimate.

There, however, might be concerns that ETI studies could potentially reflect both extensive and intensive margin responses. Nevertheless, in practice this worry is of limited concern, because these studies often focus on balanced panels around reforms, with individuals working before and after tax reform. Many studies also employ an income cutoff value, where individuals with incomes below such thresholds are discarded. For example, the paper by Matikka (2018) uses an income cutoff of 14,000 euros (close to 20,000 euros in today’s value). This means that ETI is identified from the working population in his case.6

2.3. Welfare assessments

We present results in terms of various descriptions of distributional effects, including effects on income inequality and poverty. Furthermore, we also report results for an abbreviated social welfare function, see Foster and Sen (1997), Lambert (2001), and Creedy et al. (2020). This can be characterised as employing a social welfare index depending on inequality corrected mean income.7 One may for example use the Atkinson inequality index for description of income inequality, letting assumptions about different societal preferences be reflected by the inequality aversion parameters. Denoting by the Atkinson index with inequality aversion equal to , social welfare can then be measured with , where the last term is mean income in society. We use inequality aversion parameters of 0.5, 1, or 2, where a greater value reflects higher inequality aversion.

Since the reform led to a worsening of the public budget balance, we also offer calculations of a budget-neutral reform. In our analysis, where we assume no income effects, the change in disposable income is neutralized with a lump sum tax on all. This implies that while mean income remains unaltered, there are effects of the reform on the distribution of income. The lump sum tax amount is calculated without taking behavioral effects into account.

3. A simple procedure for accounting for changed incentives

In the following we discuss in more detail how we obtain individual estimates of behavioral responses on both margins. First, we go through the procedure for extensive margin responses and thereafter how the intensive margin responses are calculated. In our simulations we follow the same order, which means that the extensive margin responses are already taken into account when calculating the intensive margin responses. The order of the simulation may slightly matter for the results.

3.1. Extensive margin response

The first step is to calculate the financial gain of working using the participation tax rate (PTR) before and after the reform:

where is the predicted earnings level, and and are household disposable income when employed and unemployed, respectively.

We restrict the calculation to individuals receiving wage income, unemployment benefits (i.e. earnings-related unemployment allowance, basic unemployment allowance or labor market subsidy) or cash-for-care benefits. In the Finnish social security context, labor market subsidy can be paid regardless of past contributions and with unlimited duration. However, certain groups that may also react to the incentives, such as disabled or pensioners, are not included.

The calculation of the participation tax rate begins by estimating hypothetical individual monthly earnings to each person in the target group. For simplicity, we focus only on the decision to work full-time or not at all and therefore we predict only earnings from full-time employment. Earnings are not observed for those not working, which is why individual earnings are obtained through regressions, where individual characteristics such as age, gender, marital status, education level, occupation, the ages of children, dwelling region, work history, debt and months of unemployment during the year are used to predict earnings.8 Earnings predictions are used both for the employed and unemployed so that the potential prediction bias pertains symmetrically to both population groups. To prevent unrealistically low predicted earnings we set minimum earnings from full-time work to 1,450 euros per month.

After estimating the earnings, we simulate the disposable income in both states. When employed, the disposable income is a function of predicted earnings, taxes, possible income-tested in-work benefits and possible day care fees. In the case of unemployment, disposable income includes the net unemployment benefit (or the cash-for-care benefit if the individual has received it), and top-up transfers, such as the housing benefit and social assistance. The unemployed are assumed to take care for their children at home and therefore no day care fees are calculated. This assumption is a simplification and in real life, choices vary by household, see Haataja et al. (2017) for evidence for Finland. Since we calculate incentives at individual level, the PTR is calculated separately for the household head and his/her spouse.

After calculating PTRs before and after the reform, we estimate the employment effect. First, we obtain a macro-level estimate of the employment effect because the external elasticity parameters are estimated at population group level and not all individuals are likely to react. Moreover, our analysis is restricted to one year interval which limits the reaction for many individuals (e.g. the whole year unemployed may not be more unemployed when facing weakened incentives). We use the following formula (see e.g. Immervoll et al., 2007),

where is the average PTR among individuals in the work force in the before-change benchmark, is the change in one minus average PTR, is an externally chosen participation elasticity parameter (of which choice of parameter we have already discussed), and is a measure of employment in the benchmark (in person-years). Effects on participation are calculated separately for those with decreased and increased participation tax rates. We use the same participation elasticity estimate for all in our main analysis, but we also obtain results with heterogeneous elasticity as a robustness check. This is applied by allowing participation elasticity to vary according to gender and the age of the youngest child (see Appendix B for full details).

To obtain micro-level distributional effects, the macro-level effect must be allocated to individuals. The estimated elasticities are averages and not all employed (or non-employed) would react. There are multiple strategies to allocate the effect, e.g., random drawing, estimated employment probabilities or the adjustment of the unemployment and employment spells. In this context where the reform focuses on increasing unemployment benefits, we choose to adjust the unemployment spells. This crude approximation is related to other contributions to the empirical literature (Lalive et al., 2006; Uusitalo and Verho, 2010). However, it should be noted that this procedure may not be suitable for other types of reforms.

The individual extended (or shortened) unemployment spell is calculated by,

where is the observed unemployment days of individual in the data and is the sum of unemployment days in the sub-population on which the unemployment effect is allocated. Because of the data restriction to a one year time frame, all unemployment spells, , are restricted to the maximum of one year. Therefore, an iterative loop is applied that extends employment spells up to one year until the macro-level employment effect is reached. After adjustment of the unemployment spells, we simulate the taxes and benefits again to obtain the net effect on disposable income.

The changes in incentives typically vary between individuals, which in turn likely implies that there is variation in the behavioral effects. Therefore, to get more precise measures of distributional effects, we weigh the individual effect in equation (3) with the individual relative change in , denoted as . The average weight is calibrated to 1 by dividing the individual changes by the mean change. Formally, the weight of individual is seen as

3.2. Intensive margin response

We measure the financial incentives to work at the intensive margin with the effective marginal tax rate, EMTR. It is defined as

where is the disposable household income following from gross labor income and denotes the extra unit added to the earnings in the calculation of marginal tax rates.

We calculate the EMTRs for individuals aged between 18 and 68, who have labor income (from employment or self-employment). The calculation of the EMTR is done separately for household head and his/her partner. The extra unit of income, , is set to 1,200 euros per year (i.e., 100 euros per month), but we run robustness checks with a higher addition of 6,000 euros per year.9 We prefer to add a small fixed income amount rather than multiply existing incomes with a small percentage because of the presence of very small incomes, which may lead to unrealistically low income additions.

After obtaining the EMTRs in both the baseline and the reform cases, we estimate the effect on taxable income, , on the individual level. We follow Saez et al. (2012) and estimate the change in taxable income as,

where is the elasticity of taxable income, is the individual’s taxable income, which in our specification is restricted to gross labor income (excluding benefits and capital income), is the effective marginal tax rate with the base year legislation, and is the change in the one minus effective marginal tax rate for the individual.

Finally, we add the calculated change in taxable income to the individual’s original taxable income and obtain estimates of the total effect on disposable income – both including the direct (mechanical) effect and the effect coming from the behavioral response.

4. Policy change used in the empirical illustration

4.1. Changes in social benefits

In the following we demonstrate the empirical framework by addressing the effects of tax-benefit policy changes that were introduced in Finland in the beginning of 2020. The changes can be summarized as modest increases in social benefits and involves both tax increases and decreases.

The most notable changes in benefits from the perspective of work incentives were the increases in unemployment benefits. The basic unemployment benefit and labor market subsidy were increased by 20 euros per month (+4 percent) and earnings-related unemployment benefits by 10-30 euros per month. The higher benefit rates (above a threshold) were increased by 30 euros and lower rates by 10 euros per month.

The so-called activation model of unemployment benefits was abolished. Having been in force since 2018 its purpose was to increase work incentives of the unemployed by cutting the unemployment benefits of passive individuals (i.e. individuals who do not fulfill the activity condition) by 4.65 percent, which corresponds to one working day per month. The activity condition could be fulfilled not only by working, more than 18 hours a month, but also by participating in active labor market policy measures (ALMP). Therefore the effect of the activation model on work incentives is ambiguous. In addition, its effect on employment could not be estimated (Kyyrä and Naumanen, 2019). Consequently, the activation model is ignored in this study when calculating PTR and EMTR changes, but it is accounted for in the non-behavioral simulations. Because activation model legislation is not included in the SISU model, it has been added manually. The incidence of the benefit reduction is calibrated to equal unemployment benefit statistics in 2019 (FIN-FSA, 2020), by using the number of so-called passive unemployment days (i.e. days when unemployed is not working part-time nor participating in employment promoting services), see Tervola (2019).

There were also changes that were assumed not to affect work incentives or have behavioral effects but still having distributional effects.10 Most importantly the minimum pension benefits, i.e., guarantee pension and national pension, were increased by maximum 50 euros per month. The housing benefit for pensioners was also increased and the minimum levels of sickness and parental benefits were increased by 20 euros per month. The increase in the minimum sickness benefit is not simulated because of data restrictions.

Furthermore, the child benefit for the 4th and 5th child and for single parents were increased, as was the social assistance for single parents. Finally, study grants were tied to the national pension index and were therefore increased. Also, most social benefits were uprated by the automatic index adjustments.

4.2. Changes in taxation

The tax changes meant that some taxpayers saw tax increase whereas others experienced a tax decrease. The tax cuts included increases of tax credits, such as the earned income tax credit and the low income tax allowance. In addition, income limits for the earned income tax scheme were increased by approximately 3 percent. There were also several tax increases. Most notably, the average municipal tax rate increased from 19.88 to 19.97 percent. In addition, the amount of domestic help credit and the tax deduction for mortgage interest payments were decreased.

Some of the mandatory social contribution payments were also changed: the mandatory pension contribution payment was increased by 0.4 percentage points and the medical care contribution of wage earners by 0.68 percentage points. On the other hand, the unemployment insurance contribution was decreased by 0.25 percentage points and daily allowance contribution for wage earners by 0.36 percentage points.

5. Simulation results

Next, we discuss the results of the policy changes given our empirical approach. First, we provide the results on work incentives and the employment effects that follow. Thereafter, we present the effects on the income distribution, poverty, fiscal revenues and overall social welfare. All calculations are conducted based on the following specifications, which we denote as a default specification: monetary parameters are adjusted according to the consumer price index, elasticities are set to 0.2 for both the extensive and intensive margins, and the EMTR is calculated by an increase of 1,200 euros per year. Results of various robustness checks are also referred to. More details are presented in Appendix B and in Ollonqvist et al. (2021).

5.1. Results on employment and fiscal responses

5.1.1. Extensive margin responses

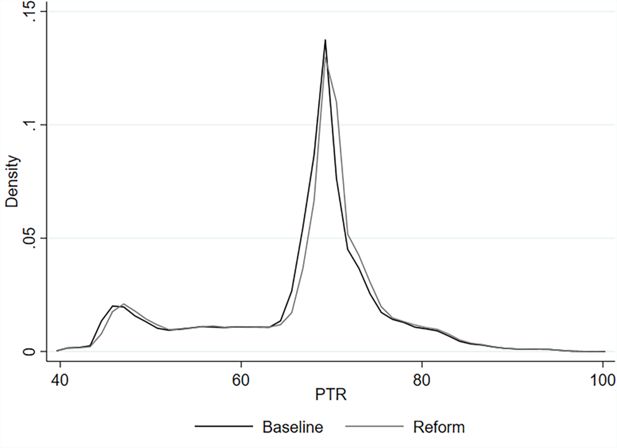

Figure 1 shows the distribution of simulated participation tax rates following from tax-benefit schemes of the baseline (black line) and the reform (gray line). For both cases the PTR is concentrated around the 70 percent mark. Moreover, the changes in tax-benefit schemes have mainly increased PTRs, i.e., decreased the financial incentives to work. On average the change is 0.5 percentage point and it is rather uniformly distributed across the different levels of the PTR.

Kernel density distributions of participation tax rates simulated with the baseline and reform legislations.

The variation in the PTR is mainly caused by variation in the level of support when unemployed. Table 1 shows the mean PTRs in baseline and reform cases by receipt of different benefits and employment. Not surprisingly, individuals receiving earnings-related unemployment benefit face the highest PTR (69.3 percent in baseline), whereas the lowest ones are seen for individuals receiving home care allowance (54.8 percent in baseline). In particular, the PTRs were increased for recipients of earnings-related unemployment benefits and the employed. However, the abolition of the activation model is not taken into account in the calculations of financial incentives and including it would most likely slightly decrease the baseline PTRs for those receiving unemployment benefits.

PTR change by benefit receipt.

| Freq | PTR baseline | PTR reform | Change, pp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flat rate UB | 280 000 | 62.7% | 62.9% | 0.1 |

| Earnings-related UB | 270 000 | 69.3% | 69.7% | 0.4 |

| Home care allowance | 100 000 | 54.8% | 54.7% | -0.1 |

| Employed | 1 890 000 | 66.6% | 67.2% | 0.5 |

| Total | 2 540 000 | 66.0% | 66.5% | 0.5 |

-

Note: If individual have several income sources within a year the following prioritization is used: 1. Home care allowance, 2. Earnings-related UB and 3. Flat rate UB. Employed are individuals with positive labor income and not received home care allowance or any unemployment benefit within a year. Baseline refers to legislation of year 2019 and reform to legislation of year 2020.

Table 2 summarizes the incentive changes and the employment effects at the extensive margin, separately for those whose incentives to work became stronger and weaker. The results are shown for three cases: 1) baseline case; 2) with heterogeneous participation elasticity; and 3) with elasticities of 0.1 and 0.3 (values in parentheses). Work incentives weakened for more than 2.2 million individuals whereas for around 270,000 individuals they became stronger. The average increase of the PTR was 0.5 percentage points and the average decrease was 0.3 percentage points.

Extensive margin responses.

| Default | Heterogenous | |

|---|---|---|

| elasticity | ||

| PTR increase (pp.-change) | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Population with increase | 2,260,000 | 2,260,000 |

| PTR decrease (pp.-change) | - 0.3 | - 0.3 |

| Population with decrease | 270,000 | 270,000 |

| Employment increase (person years) | 200 (100 – 300) | 200 |

| Employment decrease (person years) | - 5,800 (-2,900 – -8,800) | - 5,700 |

| Net change (person years) | - 5,700 (-2,800 – -8,500) | - 5,500 |

-

Note: Results are calculated with consumer price index and using the aggregate participation elasticity of 0.2. In heterogeneous elasticity column the aggregate participation elasticity is weighted using 8 different groups. The changes in PTR are the average changes and the values in brackets are formed using elasticities of 0.1 (LHS) and 0.3 (RHS). Values of employment changes are rounded to 100 units. Values of population with increase or decrease are rounded to 10,000 units.

Our default estimation of the reform yields a net decrease of employment by 5,700 person-years. Incorporating heterogeneity in elasticity estimates does not alter the results much; it gives a net decrease in employment by 5,500 person-years. Using a higher elasticity estimate (0.3) implies that the net decrease of employment would increase to around 8,800 person-work-years, while with a lower elasticity estimate (0.1), the decrease would be approx. 2,800 person-years.

5.1.2. Responses on the intensive margin

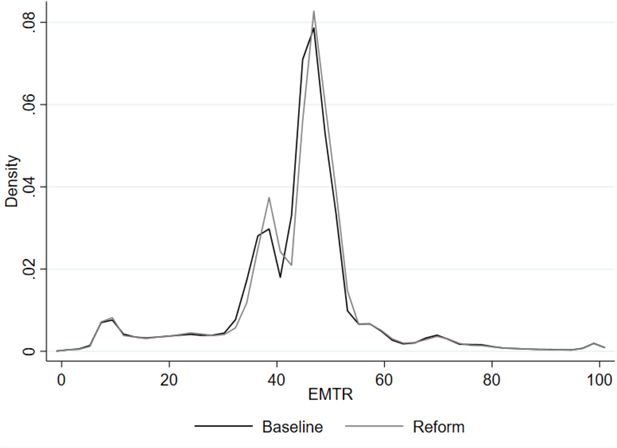

A large majority of EMTRs are found between 30 percent and 55 percent, see Figure 2. The changes in the EMTRs between baseline (black line) and reform (gray line) are rather modest, but still visible. For most individuals, EMTRs have increased and the financial incentives to work have therefore weakened after the reform.

Kernel density distributions of effective marginal tax rates simulated with the baseline and reform legislations.

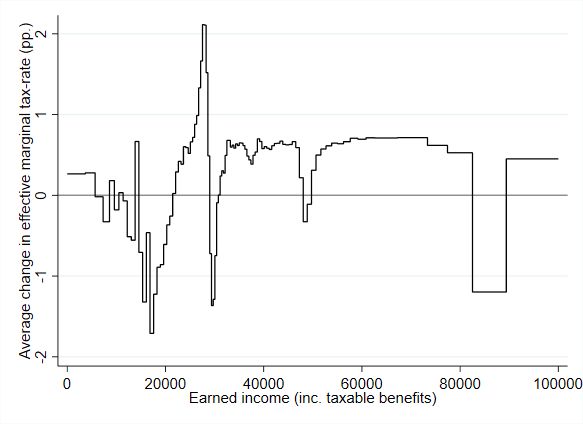

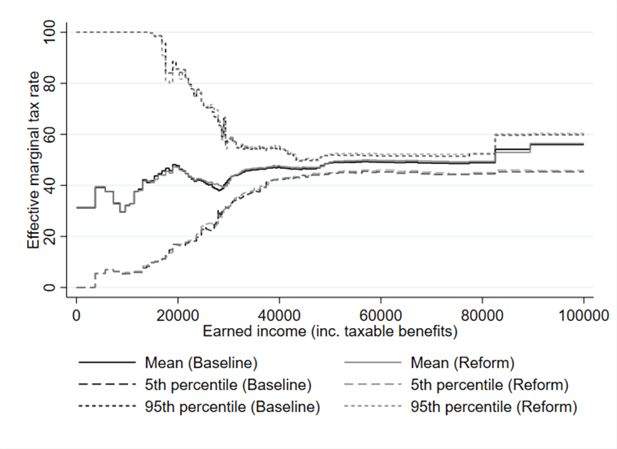

Figure 3 demonstrates that the policy changes primarily have increased EMTRs for high-earning individuals. This is mainly due to an increase in the average municipal tax rate and social contribution payments. Because the index adjustments of the tax kinks are larger than the increase in the consumer price index used to deflate the parameters, Figure 3 shows that as there are income intervals with tax cuts. For those earning less than 22,000 euros per year, effective marginal tax rates have mainly decreased, which is likely explained by increased tax credits.

Table 3 shows the mean changes in the EMTR and the corresponding behavioral effect in terms of effects on earnings, given the different assumptions. Again, the results are calculated separately for those whose incentives to work became stronger and weaker. The results are displayed for three cases: 1) baseline specification; 2) using higher level of extra income (500 euros/month) in the calculation of the EMTR; and 3) with elasticity estimates of 0.1 and 0.3. As for the extensive margin, a large majority of individuals face weakened work incentives – about 1.9 million individuals. Only around 350,000 individuals see strengthened incentives at the intensive margin. However, the average decrease in the EMTR (3.0 percentage points) is much larger than the average increase (1.0 percentage points).

Changes in incentives and earnings in intensive margin with various specifications.

| Default | Extra income | |

|---|---|---|

| of 6,000 euros/year | ||

| EMTR increase (pp-change) | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| Population with increase | 1,920,000 | 1,920,000 |

| EMTR decrease (pp-change) | -3.0 | -1.2 |

| Population with decrease | 350,000 | 390,000 |

| Earnings increase (Me) | 120 (60 – 180) | 40 |

| Earnings decrease (Me) | - 250 (-130 – -380) | - 190 |

| Net change (Me) | - 140 (-70 – -200) | - 150 |

-

Note: Default results are calculated with extra income of 1,200 euro/year. All cases are calculated using consumer price index. Values in brackets are calculated using elasticities of 0.1 (LHS) and 0.3 (RHS). Me refers to millions of euro. Values of earnings changes are rounded to 10 million euros. Values of population with increase or decrease are rounded to 10,000 units.

The net effect on gross earnings depends on the assumptions. Our baseline estimate for the net change is -140 million euros. Applying a larger extra income in the calculation of EMTR yields much smaller changes in work incentives than our baseline estimation, but the net effect on gross earnings is almost the same, -150 million euros. Dependent on assumptions with respect to the size of the elasticity of taxable income estimate, the estimated net effect varies from -70 million euros (elasticity estimate of 0.1) to -200 million euros (elasticity estimate of 0.3). All estimation results indicate that the behavioral effects at the intensive margin had a negative average impact on individuals’ gross earnings.

5.2. Effects on income inequality, poverty and fiscal revenues

According to Table 4, the policy changes decreased income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, by 0.3 percentage points. The reduction is primarily driven by the non-behavioral effect; estimated behavioral effects at the extensive and intensive margins have very small effects on income inequality.11 Table 4 reveals that median income is reduced by the behavioral responses, which is not surprising given that the large majority of the individuals faced diminished incentives to work due to the reform. Still, the estimated behavioral responses are overall rather modest and the impact is largely similar across income deciles and therefore behavioral effects do not generate any significant change in the overall dispersion of income. We will discuss this matter more thoroughly shortly.

Policy effects on inequality and poverty indicators.

| Base level in 20 | Non-behavioral | Extensive margin | Intensive margin | Both margins | Total effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gini coefficient | 28 | -0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -0.3 |

| Equalized income | ||||||

| Median | 24,335 | 54 | -29 | -17 | -47 | 7 |

| At risk of poverty | ||||||

| Whole population (%) | 13.4 | -0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -0.6 |

| Whole population (N) | 738,000 | -32,500 | 2,000 | -200 | 1,600 | -30,900 |

| Children (%) | 12.6 | -0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | -0.4 |

| Children (N) | 133,600 | -4,600 | 600 | 100 | 600 | -3,900 |

| Elderly (%) | 12.7 | -1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -1.4 |

| Elderly (N) | 150,100 | -16,200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -16,200 |

| Fiscal changes | ||||||

| Taxes (Me) | 35,700 | 130 | -40 | -70 | -110 | 20 |

| Benefits (Me) | 13,600 | 360 | 90 | 0 | 90 | 450 |

| Taxes-benefits (Me) | 22,100 | -230 | -140 | -70 | -210 | -430 |

-

Note: Results are calculated with consumer price index, elasticities of 0.2 and extra income of 1 200 euro/year. Total effect is the sum of non-behavioral and behavioral effects. Extensive margin, intensive margin and both margins are calculated compared to the reform’s (2020) non-behavioral simulation. Non-behavioral and total effect are calculated compared to the base level results. Poverty line used is set to 60% of median income and it is fixed to the baseline (2019) level. Children are defined as individuals aged less than 18 years. Elderly are defined as individuals aged 65 or more. Changes of individuals in at risk of poverty are rounded to 100 individuals. Fiscal changes are rounded to 10 million euros and baseline values of taxes and benefits are rounded to 100 million euros.

The effects on poverty, based on a fixed poverty line of 60 percent of median equivalent income, are rather similar to the effects on income inequality. Overall, poverty is reduced by 0.6 percentage points. In particular, poverty among the elderly is reduced (-1.4 percentage points). Furthermore, estimated behavioral changes have only small effects on poverty. The estimated increase in unemployment at the extensive margin yields 2,000 new individuals in poverty, which however does not change the poverty rates much. The changes at the intensive margin give even smaller effects. The lack of effects from behavioral changes is partly due to the fact that policy changes were directed towards pensioners and work-responses among the retired are ignored, as they are close to zero.

Table 4 shows that due to the non-behavioral effects, taxes and payments collected by the government increased by 130 million euros, whereas the increase in benefits paid was larger; 360 million euros. The fiscal non-behavioral net effect of the change was therefore -230 million euros. Extensive margin behavioral responses increased the total benefits paid (90 million euros), whereas responses at the intensive margin had no effect on the total benefits paid. In contrast to non-behavioral effects, the behavioral responses at both margins decrease the tax amount collected modestly. At the intensive margin, the tax revenue collected decreases by about 70 million euros, suggesting that around half of the intensive margin effect on taxable income is translated into a loss in tax revenues (see Figure C4 for more information about the effective marginal tax rates). Due to the extensive margin effects causing an increase in unemployment, there is a corresponding decrease in taxes collected (attributed to the loss of earnings and the rise in non-taxable benefits) by approximately 40 million euros. The total effect, therefore, on taxes and payments are close to zero (20 million euros), whereas the benefits paid increased by 450 million euros in total. Together, the total net fiscal effect for the government was -430 million euros, which means that the behavioral effects added to the weakening of the budget balance – despite that we employ relatively small labor supply elasticity estimates.

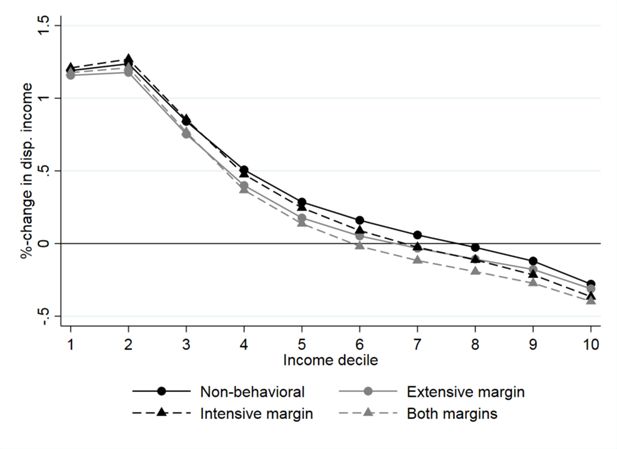

The overall pattern of the effect on disposable incomes is clear – households in the lowest deciles benefit whereas the higher deciles lose, on average (Figure 4). The lowest decile has an average 1.2 percent increase in disposable incomes, whereas the decrease for the top decile is around 0.4 percent. Again, we see that the behavioral effects have relatively small effects on changes across deciles of disposable income.

The differences between effects of non-behavioral and behavioral simulations are further illustrated in Figure 5. The responses at the extensive margin (measured by the black solid line) have a U-shaped effect and is negative for all deciles. As effects are fairly symmetric across the income distribution, the extensive margin effects have very limited effect on income inequality measured by the Gini coefficient.

The responses at the intensive margin (gray solid line) increased income for the households in the bottom three deciles and decreased income for the other deciles. These results reflect the changes in the EMTR, as described by Figure 3. For the top three deciles, the responses at the intensive margin have larger magnitude than the extensive margin responses. The total behavioral effect with respect to deciles (dotted line) can also be characterized as U-shaped, where the largest negative effect is seen for decile six.

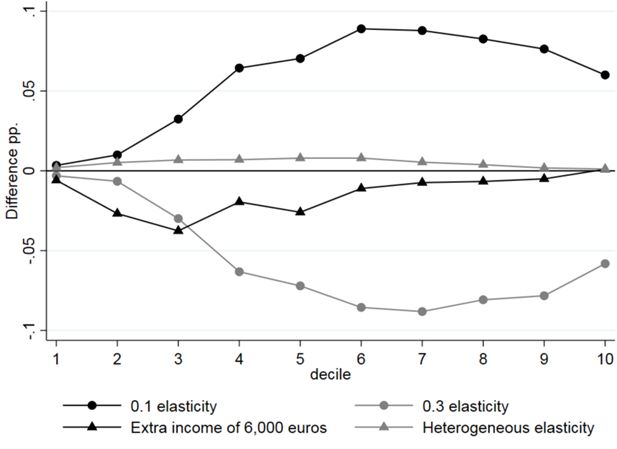

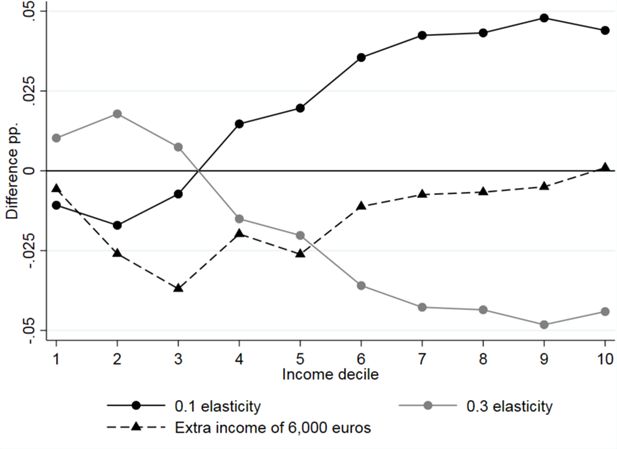

In Figure 6, estimated effects on household disposable incomes are presented by income decile for five different specifications: 1) Default specification (black circle), 2) with elasticity estimate of 0.1 (gray circle), 3) with elasticity estimate of 0.3 (black triangular), 4) using heterogeneous extensive margin elasticity estimates (gray triangular) and 5) using extra income of 6,000 euros/year and (black cross). In all cases, both non-behavioral effects and behavioral effects are included. However, specifications differ only with regard to behavioral effects, so the impact of non-behavioral effects is consistent across all scenarios. Overall the differences between the specifications are very small and the choice of the specification does not appear to play an important role in our study. The largest differences are observed when using larger or smaller elasticity, with very small effects found in the first income decile, gradually increasing up to the sixth decile. In Appendix B, we provide a more detailed presentation of results with respect to specification differences.

5.3. Social welfare effects

We also refer to how results can be summarized in terms of an abbreviated social welfare function.12 Since the policy changes led to an increase in mean income and a reduction in inequality, social welfare increases, see Table 5. The increase is more pronounced for higher values of inequality aversion.

Social welfare effects.

| Base level | Difference to base | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in 2019 | Non-behavior | Extensive | Intensive | Both margins | |

| 7.2 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 | |

| 12.7 | -0.2 | -0.2 | -0.2 | -0.2 | |

| 22.9 | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.4 | -0.4 | |

| Mean equivalized disp. income | 27,796 | 46 | 25 | 29 | 8 |

| 25,791 | 72 | 51 | 58 | 37 | |

| 24,254 | 94 | 74 | 84 | 63 | |

| 21,438 | 130 | 112 | 124 | 107 | |

-

Note: Inequality of the base situation and the change after the reform (Upper panel), with or without behavioural reactions and with Atkinson index with inequality aver sion equal to 0.5, 1, or 2. The lower panel depicts social welfare and the change relative to the base situation.

If the reform is modified through the use of lump-sum transfers to obtain revenue neutrality in the non-behavioral case, the behavioral responses result in reductions in mean income due to lower labor supply (Table 6). The social welfare consequences vary with respect to assumptions on inequality aversion. With mild inequality aversion, the reform would lead to a reduction in social welfare – due to a higher weight on average income, whereas with higher values for inequality aversion, the reform would be welfare improving – due to the reduction in inequality.

Social welfare effects, revenue neutral case

| Base level | Difference to base | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in 2019 | Non-behavior | Extensive | Intensive | Both margins | |

| 7.2 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 | |

| 12.7 | -0.2 | -0.1 | -0.2 | -0.2 | |

| 22.9 | -0.4 | -0.4 | -0.4 | -0.4 | |

| Mean equivalized disp. income | 27,796 | -14 | -35 | -31 | -52 |

| Mean disp. income,household level | 38,503 | 0 | -28 | -22 | -50 |

| 25,791 | 9 | -12 | -5 | -26 | |

| 24,254 | 29 | 9 | 19 | -2 | |

| 21,438 | 91 | 73 | 85 | 68 | |

-

Note: Inequality of the base situation and the change after the reform (Upper panel), with or without behavioural reactions and with Atkinson index with in equality aver-sion equal to 0.5, 1, or 2. The reform is made revenue neutral by levying an additional lump-sum tax to all individuals. The lower panel depicts social welfare and the change relative to the base situation.

6. Conclusion

Microsimulation is a key tool in the policy-making process. To account for behavioral responses of tax-benefit changes may pose a practical challenge. Given that the policy analyst may find it demanding to establish a fully-fledged labor supply module based on estimation and application of a structural model, the present study demonstrates how one may account for behavioral effects in microsimulation in a simpler and more practical way.

The approach we propose is to deploy extensive and intensive margin estimates from the literature, for example from the literature based on quasi-experimental approaches. Pertaining to the intensive margin, much of modern research estimates focus on the taxable income response, which, under some assumptions, could be seen as reflecting a sufficient statistic of the social welfare loss stemming from tax increase. This is because the notion contains not only possible responses in working hours but also reflects a number of other response dimensions of importance for setting the optimal tax. An additional benefit of the approach is simplicity and transparency of what is assumed about the often contentious tax responsiveness parameters.

The approach comes with alternative strategies regarding, for example, the choice of elasticity parameter or the income thresholds when calculating marginal tax rates. These choices are likely to create some variation in results and it is preferable that these assumptions are clearly conveyed and preferably one should obtain results for different choices, as we have demonstrated in the present study. However, as the external validity of the elasticity estimates may be questionable, a case-by-case evaluation of the suitability of the estimates is still needed.

The approach was illustrated with an analysis of recent Finnish policy changes. The same methods could be applied, with suitably amending, by the use of any static tax-benefit microsimulation tool. A key use of the models is, of course, examining the consequences of counterfactual policy reforms. It is, however, worth noting that the definition of policy reform itself poses challenges, which are also pertinent to other methodologies. Further work should highlight the inequality, employment, and social welfare consequences of such reforms in this transparent manner.

Footnotes

1.

As an extension, we also consider elasticity heterogeneity by groups.

2.

The labor supply module is based on a discrete choice framework, see Dagsvik et al. (2014).

3.

One may also employ evidence from event study setups, for obtaining behavioral response estimates by studies of the dynamics of labor supply changes before and after policy reforms, such as in Kleven (2024).

4.

However, the results in Jäntti et al. (2015) suggest that macro elasticities exceed micro elasticities, but not drastically so.

5.

One is often worried that quasi-experimental evidence is "history-dependent", in the sense that the results to a large extent depend on the actual policy change used in the identification. However, it is fair to say that such criticism may apply to estimates obtained from structural models too.

6.

The analysis by Neisser (2021) suggests that there is no clear relationship between the exact size of the income cutoff value and estimated elasticities.

7.

As an alternative to this one could measure welfare effects by effects on changes in money metric utility, such as equivalent variation and compensating variation.

8.

It is important to acknowledge the potential presence of a sample selection problem in the estimation of earnings. While this issue can be mitigated, for instance, through Heckman’s two-step estimation, our dataset includes information on the duration of an individual’s unemployment throughout the year. Additionally, many unemployed individuals exhibit some earnings during the year, which we also observe. This information should help us control the potential sample selection issue. Moreover, when employing the two-stage estimation, especially for men, determining which variables should be excluded is not always clear. Due to these considerations, we have opted for estimating earnings using a straightforward Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) approach. See Tables A1 and A2 in Appendix A for the model specification and the estimated coefficients.

9.

It is essential to acknowledge that, in specific tax-benefit systems, the effective marginal tax rate may be influenced not only by earned income but also by working hours. This could be attributed to factors such as eligibility for specific benefits, adjustments to earnings and unemployment benefits, or the presence of tax credits. In such systems or when wanting to capture additional hours worked, it may be more appropriate to compute the marginal tax rate by incrementally increasing working hours and adjusting annual earnings accordingly. However, in the Finnish context, this is not particularly relevant, and as a result, we solely increase earnings. Additionally, it is important to note that our dataset lacks information on working hours.

10.

For example, we ignore that the increase in child benefit has effect on labor supply through an income effect. Furthermore, changes in minimum pension benefits changed the retirement incentives at least for some individuals, but we are not modelling retirement decision in this study.

11.

The results are robust with respect to different elasticity estimates, indexation and other specifications, see Ollonqvist et al. (2021) for more details.

12.

For very small tax-benefit changes, behavioural effects could be ignored in the social welfare analysis because of the envelope theorem. Here we characterize the social welfare consequences of changes which are not only marginal for some individuals.

Appendix A

A. Regression results for earnings prediction

Regression coefficients for male wage prediction.

| Males (y=log monthly wage) | Lone dwellers | Couples | Single parents | Two parent families | Others | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coeff | p-value | coeff | p-value | coeff | p-value | coeff | p-value | coeff | p-value | |

| Intercept | 7.455 | 0.000 | 7.200 | 0.000 | 7.710 | 0.000 | 6.863 | 0.000 | 7.642 | 0.000 |

| Age | 0.027 | 0.000 | 0.024 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.035 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.000 |

| Age2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Field of education (ref. unknown or other) | ||||||||||

| Generic programmes | 0.129 | 0.019 | 0.392 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.997 | 0.477 | 0.000 | 0.285 | 0.000 |

| Education | -0.097 | 0.104 | 0.077 | 0.203 | -0.252 | 0.453 | 0.029 | 0.575 | 0.036 | 0.677 |

| Humanities and arts | -0.087 | 0.119 | 0.047 | 0.421 | -0.219 | 0.506 | 0.059 | 0.246 | 0.112 | 0.160 |

| Business and social sciences | 0.058 | 0.291 | 0.260 | 0.000 | -0.067 | 0.838 | 0.362 | 0.000 | 0.238 | 0.002 |

| Natural sciences. mathematics | 0.018 | 0.747 | 0.194 | 0.001 | -0.074 | 0.821 | 0.218 | 0.000 | 0.184 | 0.022 |

| Engineering and manufacturing | 0.115 | 0.034 | 0.308 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.957 | 0.368 | 0.000 | 0.284 | 0.000 |

| Agriculture and forestry | 0.033 | 0.558 | 0.183 | 0.002 | -0.028 | 0.931 | 0.254 | 0.000 | 0.174 | 0.028 |

| Health and welfare | 0.069 | 0.209 | 0.237 | 0.000 | -0.066 | 0.840 | 0.266 | 0.000 | 0.269 | 0.001 |

| Services | 0.056 | 0.307 | 0.254 | 0.000 | -0.042 | 0.897 | 0.300 | 0.000 | 0.242 | 0.002 |

| Level of education (ref. doctoral or equivalent) | ||||||||||

| Unknown or primary | -0.404 | 0.000 | -0.289 | 0.000 | -0.645 | 0.051 | -0.207 | 0.000 | -0.333 | 0.000 |

| Secondary | -0.471 | 0.000 | -0.533 | 0.000 | -0.619 | 0.000 | -0.527 | 0.000 | -0.547 | 0.000 |

| Post-secondary non-tertiary | -0.339 | 0.000 | -0.431 | 0.000 | -0.430 | 0.000 | -0.419 | 0.000 | -0.491 | 0.000 |

| Short-cycle tertiary | -0.306 | 0.000 | -0.312 | 0.000 | -0.373 | 0.000 | -0.295 | 0.000 | -0.350 | 0.000 |

| Master’s or equivalent | -0.087 | 0.000 | -0.062 | 0.001 | -0.058 | 0.302 | -0.017 | 0.210 | -0.138 | 0.001 |

| Ages of children | ||||||||||

| Less than 3 years (0/1) | -0.003 | 0.964 | -0.002 | 0.797 | -0.012 | 0.480 | ||||

| 3-6 years (0/1) | 0.020 | 0.525 | 0.004 | 0.421 | -0.042 | 0.006 | ||||

| 7-18 years (0/1) | -0.041 | 0.321 | -0.018 | 0.002 | -0.010 | 0.359 | ||||

| Region (ref. Lapland) | ||||||||||

| Uusimaa | 0.041 | 0.001 | 0.094 | 0.000 | 0.132 | 0.000 | 0.121 | 0.000 | 0.067 | 0.007 |

| Etelä-Savo | -0.076 | 0.000 | -0.069 | 0.000 | -0.059 | 0.168 | -0.059 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.859 |

| Pohjois-Savo | -0.056 | 0.000 | -0.040 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.770 | -0.042 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.549 |

| Pohjois-Karjala | -0.085 | 0.000 | -0.058 | 0.000 | -0.046 | 0.262 | -0.071 | 0.000 | -0.031 | 0.417 |

| Keski-Suomi | -0.044 | 0.003 | -0.028 | 0.045 | 0.003 | 0.941 | -0.017 | 0.162 | -0.012 | 0.709 |

| Etelä-Pohjanmaa | -0.084 | 0.000 | -0.072 | 0.000 | -0.030 | 0.455 | -0.089 | 0.000 | -0.067 | 0.067 |

| Pohjanmaa | -0.062 | 0.000 | -0.007 | 0.661 | 0.004 | 0.925 | -0.029 | 0.028 | -0.038 | 0.288 |

| Keski-Pohjanmaa | -0.048 | 0.035 | -0.033 | 0.120 | -0.008 | 0.884 | -0.033 | 0.058 | -0.053 | 0.276 |

| Pohjois-Pohjanmaa | -0.031 | 0.023 | -0.030 | 0.024 | -0.001 | 0.982 | -0.011 | 0.320 | 0.009 | 0.771 |

| Kainuu | -0.067 | 0.001 | -0.055 | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.857 | -0.052 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.918 |

| Varsinais-Suomi | -0.042 | 0.002 | -0.012 | 0.344 | -0.015 | 0.648 | -0.016 | 0.151 | -0.030 | 0.289 |

| Satakunta | -0.012 | 0.425 | 0.009 | 0.524 | 0.054 | 0.132 | 0.003 | 0.790 | 0.023 | 0.490 |

| Kanta-Häme | -0.016 | 0.297 | -0.003 | 0.841 | 0.038 | 0.315 | 0.004 | 0.750 | 0.007 | 0.839 |

| Pirkanmaa | -0.049 | 0.000 | -0.005 | 0.703 | 0.032 | 0.319 | 0.004 | 0.731 | -0.024 | 0.404 |

| Päijät-Häme | -0.025 | 0.108 | -0.011 | 0.466 | 0.071 | 0.073 | -0.009 | 0.475 | -0.008 | 0.807 |

| Kymenlaakso | 0.022 | 0.164 | 0.051 | 0.001 | 0.077 | 0.057 | 0.017 | 0.209 | -0.009 | 0.805 |

| Etelä-Karjala | -0.013 | 0.451 | 0.013 | 0.415 | 0.082 | 0.066 | -0.008 | 0.617 | 0.003 | 0.945 |

| Months in unemployment during the year (ref. more than 8) | ||||||||||

| Less than 3 | 0.192 | 0.000 | 0.164 | 0.000 | 0.293 | 0.018 | 0.160 | 0.000 | 0.131 | 0.012 |

| 3-5 | 0.105 | 0.002 | 0.081 | 0.064 | 0.225 | 0.073 | 0.054 | 0.187 | 0.063 | 0.252 |

| 6-8 | 0.033 | 0.417 | -0.108 | 0.031 | 0.185 | 0.165 | 0.012 | 0.806 | 0.008 | 0.901 |

| Employment days | 0.063 | 0.000 | 0.076 | 0.000 | 0.074 | 0.000 | 0.076 | 0.000 | 0.052 | 0.000 |

| (100) in prev. year | ||||||||||

| Existing debt (0/1) | 0.113 | 0.000 | 0.082 | 0.000 | 0.135 | 0.000 | 0.096 | 0.000 | 0.121 | 0.000 |

| Married (0/1) | 0.066 | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.000 | 0.081 | 0.000 | 0.045 | 0.000 | 0.060 | 0.000 |

| Income of other hh members (log €) | 0.007 | 0.000 | -0.005 | 0.001 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.049 | ||

Regression coefficients for female wage prediction.

| Females (y=log monthly wage) | Lone dwellers | Couples | Single parents | Two parent families | Others | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coeff | p-value | coeff | p-value | coeff | p-value | coeff | p-value | coeff | p-value | |

| Intercept | 7.522 | 0.000 | 7.385 | 0.000 | 7.459 | 0.000 | 7.130 | 0.000 | 7.591 | 0.000 |

| Age | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.000 |

| Age2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.113 |

| Field of education (ref. unknown or other) | ||||||||||

| Generic programmes | 0.372 | 0.000 | 0.338 | 0.000 | 0.259 | 0.000 | 0.399 | 0.000 | 0.408 | 0.000 |

| Education | 0.216 | 0.002 | 0.172 | 0.002 | 0.024 | 0.733 | 0.117 | 0.008 | 0.272 | 0.000 |

| Humanities and arts | 0.201 | 0.004 | 0.157 | 0.004 | 0.046 | 0.520 | 0.143 | 0.001 | 0.261 | 0.000 |

| Business and social sciences | 0.325 | 0.000 | 0.282 | 0.000 | 0.192 | 0.006 | 0.295 | 0.000 | 0.372 | 0.000 |

| Natural sciences. mathematics | 0.286 | 0.000 | 0.257 | 0.000 | 0.164 | 0.026 | 0.232 | 0.000 | 0.359 | 0.000 |

| Engineering and manufacturing | 0.349 | 0.000 | 0.313 | 0.000 | 0.234 | 0.001 | 0.346 | 0.000 | 0.366 | 0.000 |

| Agriculture and forestry | 0.257 | 0.000 | 0.247 | 0.000 | 0.115 | 0.115 | 0.222 | 0.000 | 0.288 | 0.000 |

| Health and welfare | 0.339 | 0.000 | 0.275 | 0.000 | 0.170 | 0.016 | 0.253 | 0.000 | 0.383 | 0.000 |

| Services | 0.249 | 0.000 | 0.192 | 0.000 | 0.104 | 0.141 | 0.195 | 0.000 | 0.301 | 0.000 |

| Level of education (ref. doctoral or equivalent) | ||||||||||

| Unknown or primary | -0.338 | 0.000 | -0.435 | 0.000 | -0.481 | 0.000 | -0.400 | 0.000 | -0.398 | 0.000 |

| Secondary | -0.607 | 0.000 | -0.669 | 0.000 | -0.593 | 0.000 | -0.639 | 0.000 | -0.695 | 0.000 |

| Post-secondary non-tertiary | -0.503 | 0.000 | -0.556 | 0.000 | -0.499 | 0.000 | -0.532 | 0.000 | -0.568 | 0.000 |

| Short-cycle tertiary | -0.448 | 0.000 | -0.500 | 0.000 | -0.416 | 0.000 | -0.477 | 0.000 | -0.540 | 0.000 |

| Master’s or equivalent | -0.162 | 0.000 | -0.192 | 0.000 | -0.091 | 0.001 | -0.147 | 0.000 | -0.240 | 0.000 |

| Ages of children | ||||||||||

| Less than 3 years (0/1) | 0.064 | 0.001 | 0.072 | 0.000 | -0.021 | 0.264 | ||||

| 3-6 years (0/1) | 0.021 | 0.044 | 0.023 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.729 | ||||

| 7-18 years (0/1) | 0.011 | 0.433 | 0.016 | 0.005 | -0.012 | 0.242 | ||||

| Region (ref. Lapland) | ||||||||||

| Uusimaa | 0.085 | 0.000 | 0.116 | 0.000 | 0.142 | 0.000 | 0.108 | 0.000 | 0.097 | 0.000 |

| Etelä-Savo | -0.017 | 0.320 | -0.029 | 0.022 | 0.014 | 0.575 | -0.022 | 0.085 | -0.001 | 0.987 |

| Pohjois-Savo | -0.027 | 0.075 | -0.006 | 0.560 | 0.030 | 0.170 | 0.007 | 0.546 | -0.002 | 0.940 |

| Pohjois-Karjala | -0.044 | 0.013 | -0.019 | 0.120 | 0.017 | 0.491 | -0.014 | 0.262 | -0.007 | 0.819 |

| Keski-Suomi | -0.040 | 0.008 | -0.014 | 0.190 | 0.005 | 0.810 | -0.024 | 0.025 | 0.009 | 0.749 |

| Etelä-Pohjanmaa | -0.026 | 0.117 | -0.019 | 0.121 | 0.009 | 0.698 | -0.031 | 0.006 | -0.009 | 0.767 |

| Pohjanmaa | -0.053 | 0.002 | -0.022 | 0.070 | 0.043 | 0.080 | -0.046 | 0.000 | -0.054 | 0.070 |

| Keski-Pohjanmaa | -0.032 | 0.174 | -0.024 | 0.146 | 0.005 | 0.864 | -0.049 | 0.002 | 0.015 | 0.713 |

| Pohjois-Pohjanmaa | -0.040 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.009 | 0.641 | -0.004 | 0.659 | 0.016 | 0.537 |

| Kainuu | -0.044 | 0.045 | -0.023 | 0.134 | 0.030 | 0.363 | 0.001 | 0.936 | -0.109 | 0.014 |

| Varsinais-Suomi | -0.011 | 0.380 | 0.018 | 0.074 | 0.034 | 0.074 | 0.012 | 0.198 | 0.012 | 0.612 |

| Satakunta | -0.023 | 0.134 | -0.006 | 0.604 | 0.017 | 0.429 | -0.003 | 0.772 | -0.026 | 0.378 |

| Kanta-Häme | 0.007 | 0.663 | 0.030 | 0.009 | 0.065 | 0.004 | 0.029 | 0.011 | 0.018 | 0.552 |

| Pirkanmaa | -0.012 | 0.364 | 0.017 | 0.082 | 0.053 | 0.005 | -0.004 | 0.648 | -0.009 | 0.701 |

| Päijät-Häme | -0.013 | 0.379 | 0.014 | 0.228 | 0.050 | 0.023 | -0.003 | 0.770 | 0.005 | 0.856 |

| Kymenlaakso | -0.007 | 0.643 | 0.002 | 0.852 | 0.023 | 0.316 | 0.004 | 0.750 | 0.002 | 0.948 |

| Etelä-Karjala | -0.013 | 0.460 | 0.001 | 0.960 | 0.019 | 0.452 | -0.013 | 0.306 | -0.013 | 0.730 |

| Months in unemployment during the year (ref. more than 8) | ||||||||||

| Less than 3 | 0.013 | 0.796 | 0.042 | 0.462 | 0.059 | 0.418 | 0.038 | 0.509 | 0.109 | 0.207 |

| 3-5 | -0.043 | 0.402 | -0.007 | 0.901 | -0.034 | 0.646 | -0.028 | 0.628 | 0.084 | 0.348 |

| 6-8 | -0.129 | 0.039 | -0.116 | 0.088 | -0.081 | 0.397 | -0.109 | 0.124 | -0.089 | 0.390 |

| Employment days | 0.062 | 0.000 | 0.058 | 0.000 | 0.053 | 0.000 | 0.048 | 0.000 | 0.057 | 0.000 |

| (100) in prev. year | ||||||||||

| Existing debt (0/1) | 0.079 | 0.000 | 0.062 | 0.000 | 0.103 | 0.000 | 0.068 | 0.000 | 0.075 | 0.000 |

| Married (0/1) | 0.023 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.048 | -0.009 | 0.386 | -0.002 | 0.572 | -0.014 | 0.102 |

| Income of other hh members (log €) | 0.015 | 0.000 | -0.003 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.964 | ||

Appendix B

B. Robustness checks

This section provides more details about the additional analyses conducted to examine the robustness of our findings. Full details of the robustness checks conducted are provided in Ollonqvist et al. (2021).

First, we test the effect of alternative income (6,000 euros/year) threshold when calculating EMTRs. The amount is five times the amount we used in our main spesification. Second, we use different levels of elasticity parameters and heterogeneous participation elasticity. In the main analysis we used the elasticity of 0.2 for both margins, but we conducted the analysis using the elasticities of 0.1 and 0.3 as well. In addition, we tested participation elasticities that vary according to gender the age of the youngest child in household. In total, the population is divided into eight different subgroups. The groups and respective elasticity weights, shown in Table B3, are based on Kotamäki and Kärkkäinen (2018). In the calculations, the default elasticity of participation (0.2) is weighted according to these weights. We, however, make also an ad-hoc adjustment to the heterogeneous elasticities since with our data these do not sum up exactly to aggregate participation elasticity. All of the elasticities are multiplied by 0.986 to correct the inaccuracy.

Heterogeneous weights for participation elasticity

| Women | Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of the youngest children | Over 17 years or no children | 1.28 | 0.92 |

| under 3 years old | 1.32 | 0.92 | |

| 3 to 7 years old | 1 | 0.68 | |

| 8 to 17 years old | 0.84 | 0.56 |

-

Source: Own calculations based on Kotamäki and Kärkkäinen (2018)

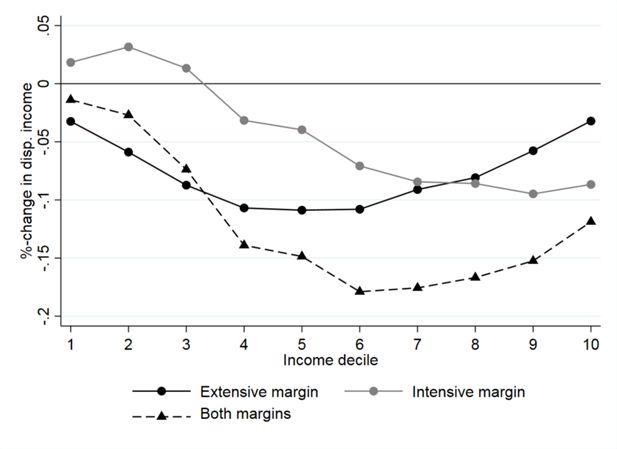

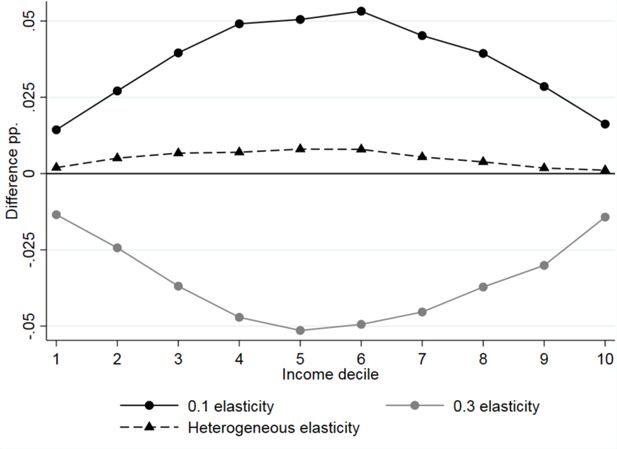

Next figures summarize how the different empirical specifications alter the results on income inequality. The differences are shown separately for each type of the effect i.e. for: 1) the extensive margin effect (Figure B1), 2) the intensive margin effect (Figure B2) and 3) the total behavioral effect (Figure B3). The last of these also reflects differences in overall (non-behavioral + behavioral) effects since specifications differ solely in terms of behavioral impacts. All of the figures show the difference compared to the baseline effect. In total four different specification is used in the following figures: 1) with the elasticities of 0.1, 2) with the elasticities of 0.3, 3) with extra income of 6,000 euros per year and 4) with heterogeneous participation elasticity. However, all of the specifications are not displayed in every figure, since some of them affect only some types of effects. Positive values indicate larger increase or smaller decrease in disposable incomes compared to baseline results and vice versa for the negative values.

The differences (pp) in the effect of extensive margin responses in relation to the default specification (=0) by income decile.

The differences (pp) in the effect of intensive margin responses in relation to the default specification (=0) by income decile.

Appendix C

References

-

1

Modelling Our Future: Population Ageing, Health and Aged Care, International Symposia in Economic Theory and Econometrics513–518, The Norwegian tax-benefit model system LOTTE, Modelling Our Future: Population Ageing, Health and Aged Care, International Symposia in Economic Theory and Econometrics, Elsevier, p, 10.1016/S1571-0386(06)16034-2.

-

2

The effect of the UK coalition government’s tax and benefit changes on household incomes and work incentivesFiscal Studies 36:375–402.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5890.2015.12058

-

3

In-work policies in Europe: Killing two birds with one stone?Labour Economics 13:667–697.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2005.10.007

-

4

Comparing labor supply elasticities in Europe and the United States: new resultsJournal of Human Resources 49:723–838.https://doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2014.0017

-

5

Own-wage labor supply elasticities: variation across time and estimation methodsIZA Journal of Labor Economics 5:10.https://doi.org/10.1186/s40172-016-0050-z

-

6

The anatomy of the extensive margin labor supply response*The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 123:33–59.https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12406

-

7

Hourly wage rate and taxable labor income responsiveness to changes in marginal tax ratesJournal of Public Economics 94:878–889.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.08.001

-

8

Handbook of Labor Economics1559–1695, Labor supply: A review of alternative approaches, Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol, volume 3, Elsevier, p, 10.1016/S1573-4463(99)03008-4.

-

9

The effect of taxation on labor supply: evaluating the gary negative income tax experimentJournal of Political Economy 86:1103–1130.https://doi.org/10.1086/260730

-

10

Sufficient statistics for welfare analysis: a bridge between structural and reduced-form methodsAnnual Review of Economics 1:451–488.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.economics.050708.142910

-

11

Adjustment costs, firm responses, and micro vs. macro labor supply elasticities: evidence from danish tax recordsThe Quarterly Journal of Economics 126:749–804.https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjr013

-

12

Are micro and macro labor supply elasticities consistent? a review of evidence on the intensive and extensive marginsAmerican Economic Review 101:471–475.https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.3.471

-

13

Does indivisible labor explain the difference between micro and macro elasticities? a meta-analysis of extensive margin elasticitiesNBER Macroeconomics Annual 27:1–56.https://doi.org/10.1086/669170

-

14

Discrete hours labour supply modelling: specification, estimation and simulationJournal of Economic Surveys 19:697–734.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0950-0804.2005.00265.x

-

15

A microsimulation analysis of marginal welfare-improving income tax reforms for New ZealandInternational Tax and Public Finance 27:409–434.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-019-09558-5

-

16

Theoretical and practical arguments for modeling labor supply as a choice among latent jobsJournal of Economic Surveys 28:134–151.https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12003

-

17